Over the past 20 years, the country’s job market has received each year roughly 230,000 new working-age Canadians, a demographic trend that’s helped the economy continue growing and delivered rising incomes.

That trend is now set to take a “steep decline” to just 90,000 a year over the next two decades, according to a new report Monday, a development that threatens to drag down Canada’s prosperity in the process.

The trouble is all those retiring baby boomers who can’t be replaced quickly enough.

And without some major measures, such as dramatically ramping up immigration quotas as well as putting the pedal down on productivity, the country’s looking at a per capita loss of income of upwards of $11,500 by RBC’s math.

The report expands on comments made by Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz earlier this month on the chilling effect that boomers’ looming retirement plans are having on the economy already.

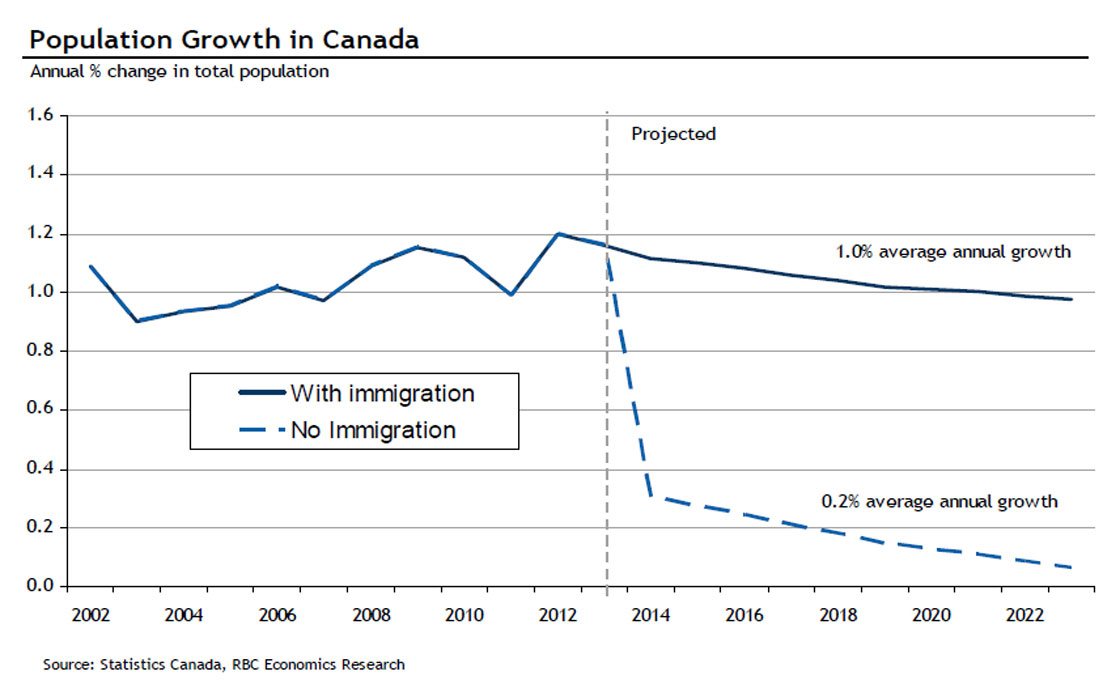

The numbers bear out the slowdown among the number of working-age Canadians.

Last year, the total population of those between 15 and 64 years old grew at the slowest pace in more than four decades. The number of those 65 or older, meanwhile, expanded by 4.2 per cent – a “near record” pace, RBC says.

The shrinking pool of workers means that the number of retirees to every 100 members of the workforce will jump to 30 by 2023, up from 22 last year.

A falling participation rate in the labour market means weakening tax revenues for governments to pay for everything from healthcare to social services.

But there is some recourse. “That said, increased levels of immigration will help close the gap,” the report said.

By how much? Canada currently admits about 250,000 immigrants annually, a number that would have to be tripled if the demographic trend is to be offset. But that’s something that’s “likely not realistic,” economist Laura Cooper, who authored the bank report, said.

The report recommends instead bolder efforts to tap “underutilized” segments of the domestic population, namely aboriginal Canadians and youth workers, where there’s higher percentages of unemployed and part-time workers compared to other cohorts.

“Creating the conditions that allow for these individuals to participate in full-time work would provide a boost to hours worked and further contribute to offsetting an easing in economic growth,” Cooper says.

- ‘Shock and disbelief’ after Manitoba school trustee’s Indigenous comments

- Several baby products have been recalled by Health Canada. Here’s the list

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Invasive strep: ‘Don’t wait’ to seek care, N.S. woman warns on long road to recovery

Comments