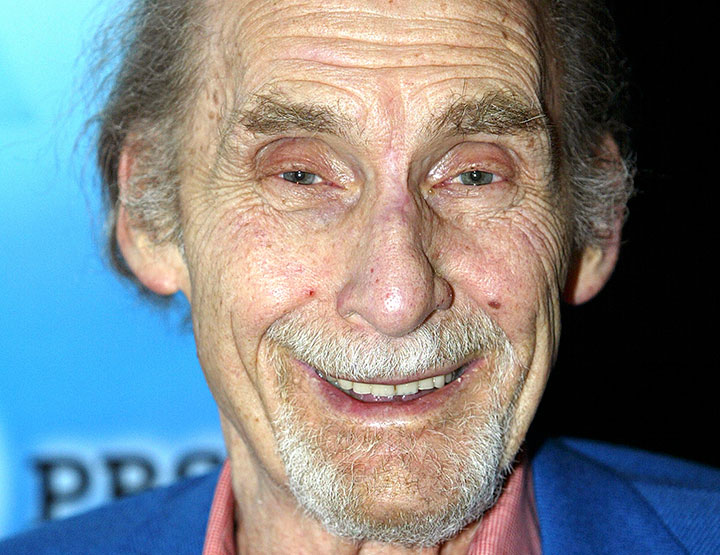

LOS ANGELES – Sid Caesar, the TV comedy pioneer whose rubber-faced expressions and mimicry built on the work of his dazzling team of writers that included Woody Allen and Mel Brooks, died Wednesday. He was 91.

Family spokesman Eddy Friedfeld said Caesar, who also played Coach Calhoun in the 1978 movie Grease, died at his home in the Los Angeles area after a brief illness.

“He had not been well for a while. He was getting weak,” said Friedfeld, who lives in New York and last spoke to Caesar about 10 days ago.

Friedfeld, a friend of Caesar’s who wrote the 2003 biography Caesar’s Hour, learned of his death in an early morning call from Caesar’s daughter, Karen.

In his two most important shows, Your Show of Shows, 1950-54, and Caesar’s Hour, 1954-57, Caesar displayed remarkable skill in pantomime, satire, mimicry, dialect and sketch comedy. And he gathered a stable of young writers who went on to worldwide fame in their own right — including Carl Reiner, Neil Simon, Larry Gelbart, and Allen.

“He was one of the truly great comedians of my time and one of the finest privileges I’ve had in my entire career was that I was able to work for him,” Allen said in a statement.

Reiner, who was a writer-performer on the breakthrough Your Show of Shows sketch program, said he had an ability to “connect with an audience and make them roar with laughter.”

“Sid Caesar set the template for everybody,” Reiner told KNX-AM in Los Angeles. “He was without a doubt, inarguably, the greatest sketch comedian-monologist that television ever produced. He could adlib. He could do anything that was necessary to make an audience laugh.”

The Friars Club called Caesar the “patron saint” of sketch comedy.

While best known for his TV shows, which have been revived on DVD in recent years, he also had success on Broadway and occasional film appearances, notably in It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World.

If the typical funnyman was tubby or short and scrawny, Caesar was tall and powerful, with a clown’s loose limbs and rubbery face, and a trademark mole on his left cheek.

Get breaking National news

But Caesar never went in for clowning or jokes. He wasn’t interested. He insisted that the laughs come from the everyday.

“Real life is the true comedy,” he said in a 2001 interview with The Associated Press. “Then everybody knows what you’re talking about.” Caesar brought observational comedy to TV before the term, or such latter-day practitioners as Jerry Seinfeld, were even born.

In one celebrated routine, Caesar impersonated a gumball machine; in another, a baby; in another, a ludicrously overemotional guest on a parody of This Is Your Life.

He played an unsuspecting moviegoer getting caught between feuding lovers in a theatre. He dined at a health food restaurant, where the first course was the bouquet in the vase on the table. He was interviewed as an avant-garde jazz musician who seemed happily high on something.

The son of Jewish immigrants, Caesar was a wizard at spouting melting-pot gibberish that parodied German, Russian, French and other languages. His Professor was the epitome of goofy Germanic scholarship.

Some compared him to Charlie Chaplin for his success at combining humour with touches of pathos.

“As wild an idea as you get, it won’t go over unless it has a believable basis to start off with,” he told The Associated Press in 1955. “The viewers have to see you basically as a person first, and after that you can go on into left field.”

In 1962, Caesar starred on Broadway in the musical Little Me, written by Simon, and was nominated for a Tony. He played seven different roles, from a comically perfect young man to a tyrannical movie director to a prince of an impoverished European kingdom.

“The fact that, night after night, they are also excruciatingly funny is a tribute to the astonishing talents of their portrayer,” Newsweek magazine wrote. “In comedy, Caesar is still the best there is.”

He was one of the galaxy of stars who raced to find buried treasure in the 1963 comic epic It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, and in 1976 he put his pantomime skills to work in Brooks’ Silent Movie.

But he later looked back on those years as painful ones. He said he beat a severe, decades-long barbiturate and alcohol habit in 1978, when he was so low he considered suicide. “I had to come to terms with myself. ‘Yes or no? Do you want to live or die?'” Deciding that he wanted to live, he recalled, was “the first step on a long journey.”

Caesar was born in 1922 in Yonkers, N.Y., the third son of an Austrian-born restaurant owner and his Russian-born wife. His first dream was to become a musician, and he played saxophone in bands in his teens.

But as a youngster waiting tables at his father’s luncheonette, he liked to observe as well as serve the diverse clientele, and recognize the humour happening before his eyes.

His talent for comedy was discovered when he was serving in the Coast Guard during World War II and got a part in a Coast Guard musical, Tars and Spars. He also appeared in the movie version. Wrote famed columnist Hedda Hopper: “I hear the picture’s good, with Sid Caesar a four-way threat. He writes, sings, dances and makes with the comedy.”

That led to a few other film roles, nightclub engagements, and then his breakthrough hit, a 1948 Broadway revue called Make Mine Manhattan.

His first TV comedy-variety show, The Admiral Broadway Revue, premiered in February 1949. But it was off the air by June. Its fatal shortcoming: unimagined popularity. It was selling more Admiral television sets than the company could make, and Admiral, its exclusive sponsor, pulled out.

But everyone was ready for Caesar’s subsequent efforts. Your Show of Shows, which debuted in February 1950, and Caesar’s Hour three years later reached as many as 60 million viewers weekly and earned its star $1 million annually at a time when $5, he later noted, bought a steak dinner for two.

When Caesar’s Hour left the air in 1957, Caesar was only 34. But the unforgiving cycle of weekly television had taken a toll: His reliance on booze and pills for sleep every night so he could wake up and create more comedy.

It took decades for him to hit bottom. In 1977, he was onstage in Regina doing Simon’s The Last of the Red Hot Lovers when, suddenly, his mind went blank. He walked off stage, checked into a hospital and went cold turkey. Recovery had begun, with the help of wife Florence Caesar, who would be by his side for more than 60 years and helped him weather his demons.

Those demons included remorse about the flared-out superstardom of his youth — and how the pressures nearly killed him. But over time he learned to view his life philosophically.

“You think just because something good happens, THEN something bad has got to happen? Not necessarily,” he said with a smile in 2003, pleased to share his hard-won wisdom: “Two good things have happened in a row.”

Comments