TORONTO – The sun, the driving force behind our weather and most life on our planet, is napping. You might too if you’d been burning for about 5 billion years.

Many point to the sun’s low activity as the cause of the recent “pause” in global surface temperatures over the past decade.

The sun, however, is getting a bad rap.

READ MORE: 2013 tied for 4th warmest year on record, NOAA

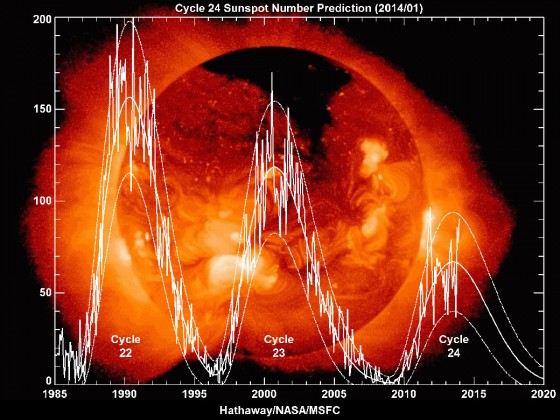

The sun goes through a cycle where it experiences a maximum and a minimum. During solar maximum, there are more sunspots and the sun is more active. During solar minimum, there are fewer sunspots and the sun is quiet.

The sun has strong magnetic field lines which are measured in Gauss. Scientists have discovered that in order for sunspots to form there has to be a field strength of around 3000 Gauss. So when the solar activity is low — at its minimum — the sun is still generating a magnetic field, just not strong enough to form sunspots.

Right now we are in Solar Cycle 24, which has been relatively quiet compared to past cycles. The strongest cycle in our recent past was Solar Cycle 19 during a period of 1957 to 1958.

Get breaking National news

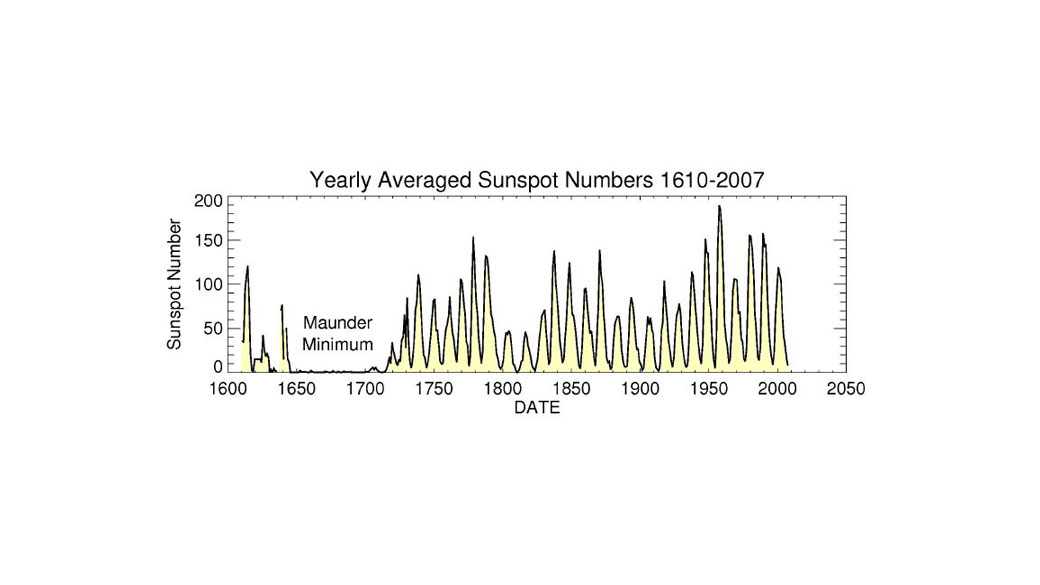

Cycle 24 has been the quietest cycle in 100 years, which is leading many to believe we are heading toward something called a Maunder Minimum.

READ MORE:Sun’s magnetic field about to flip

The Maunder Minimum was a period of extremely low sunspot activity on the sun from 1645 to 1715. There were decades with no sunspots at all, something that is incredibly rare.

The lack of sunspots also coincided with a period termed the Little Ice Age that extended from the mid-1500s right into the early 1800s. Mean annual temperatures decreased by 0.6 C (as compared to the average temperature from 1000 and 2000 AD, as analyzed by ice cores and tree rings). Temperatures were unusually harsh in Europe: the Thames River in England froze; glaciers advanced.

Is this where this solar activity says we’re heading?

Though the sunspots can cause some cooling on the planet, Hathaway believes that it’s human activity that has more of an influence on global temperatures.

“There is the possibility that we are heading into a grand minimum like the Maunder Minimum, but I think that even if we did — and there are studies by my colleagues that have looked at exactly that — if we did go into a grand minimum, with no sunspots for decades, would it stop global warming? And the answer was, no.

“It’s a lull and the sun may slumber for a while.”

What influences our global temperatures more is human activity. Since 1880, the world’s average temperature has risen almost 1 C.

“As far as the temperature differences that we see or infer as related to the sun are small. They’re a tenth, two-tenths of a degree centigrade and global warming gives you that much change in a decade or thereabouts,” said Hathaway.

Canadian astronomer Paul Mortfield isn’t worried about Earth heading toward another Little Ice Age.

“If the sun was to consistently be generating less energy over decades, hundreds of years, that’s something to be concerned about. But the fact that we have the cycle that we have right now… Maybe the next one will go back to normal again. Or maybe this will be the way it’ll be for 100 years. Again, you’re talking about a tenth of a degree.

“The sun isn’t cooling and going out. It’s still got enough energy in there, enough hydrogen to keep it fuelled,” Mortfield said. “It’s not like it’s shutting down.”

Mortfield was the chair of the Solar Division of the American Association of Variable Stars, a group that is responsible for computing the American Relative Sunspot numbers for more than 60 years, from 2006-2011.

“We’re dealing with a star that has a life cycle of about 9 billion years,” said Mortfield. “And we’ve only been monitoring sunspots for about 300 or 400 years.”

Mortfield noted that the sun has experienced dips in solar activity before such as the early 1800s, but then solar activity began to increase. Only time will tell whether or not we’re indeed heading into something astronomers call a “grand minimum” like the Maunder Minimum.

“The sun is very nicely providing us with this experiment,” Hathaway said about knowing for sure whether or not we’re headed toward a minimum.

“So I’m not going to retire for a while,” Hathaway said, laughing. “I want to see what the answer is.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.