A new 22-acre development, located in a residential area of Metro Vancouver, doesn’t need to get approved by city council.

That’s because there isn’t any.

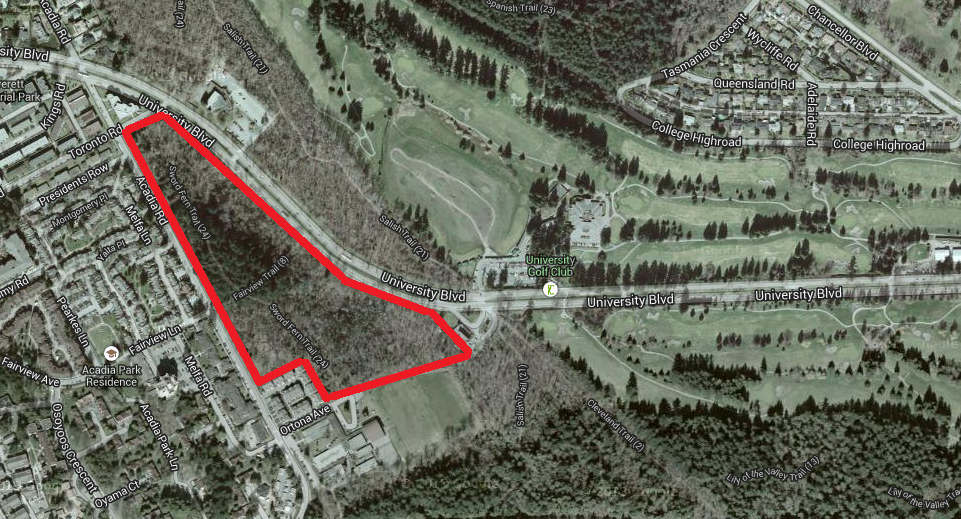

A proposed development by the Musqueam First Nation next to the University Golf Club has the general support of people in the University Endownment Lands (UEL), the area between the City of Vancouver and the University of British Columbia.

“We’re not against the proposal, we just want to make it appropriate for the community, and I think in most cases it’s pretty good,” says Ron Pears, president of the UEL’s community advisory council.

The Musqueam’s plan for the forested area calls for a mix of single-family housing, some mixed-use towers, a hotel, and a daycare.

The approval process, like anything else in the UEL, will be overseen by the provincial government. Pears says it highlights the lack of local governance for their region, which numbers over 4000 people.

“We need to be better governed. We’re not governed now, we’re managed,” says Pears. “The lights get turned on at night, the trash gets picked up, things happen…but nobody’s looking at the future.

Get breaking National news

“We don’t know where we’re going, we’re steering blindly down the channel. It’s not a good way to run a community. It’s not democracy, there’s no representation or democracy here.”

The UEL was created by the provincial government in 1907 to raise funds for a new university. Over the decades, residential lots next to UBC were directly sold to residents, who have benefited as property values have skyrocketed. The average value of a house is around $5.1 million, while the entire operating budget for the UEL is $7.5 million.

However, the land has no municipal representation, instead relying on the advisory council, while contracting out basic services and having all zoning decisions made by the provincial government. They, along with UBC, elect one person to the Metro Vancouver board.

A local government wasn’t seen as necessary when the population was low and the area was barely developed. But as the population and services in the area have increased, so too have concerns from residents.

“It works okay, because we have services,” says Pears. “But what we don’t have is governance. We don’t have a council to say we want that or don’t want that.”

The provincial government has shown no interest in changing the governance for either the UEL or UBC, which has also created its own small city with thousands of residents over the past decade. The status quo looks to continue for some time. And that, says Pears, is frustrating.

“Nobody lives in the endowment lands. Not a single person that services us lives in here. Now that’s pretty weird.

Most people have an elected council, and that’s important.”

Comments