The gap between Ontario’s housing stock and its rapid population growth is the widest it has been since records began, according to a development industry report that throws fresh doubt on the Ford government’s ability to hit its own target of building 1.5 million homes by 2031.

A new study commissioned by an advocacy group, the Building Industry and Land Development Association, compared housing application data across 16 Ontario cities to find those with the best approval rates, capturing a continual slowdown of the building industry.

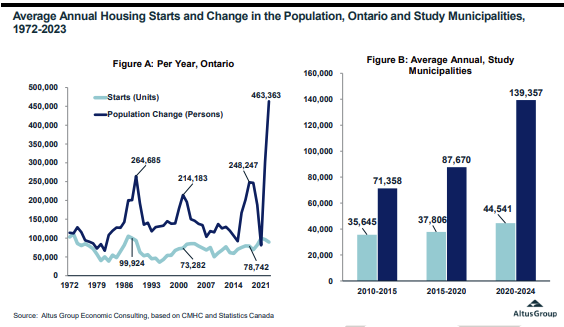

Among the report’s findings was the fact that record immigration and population growth in and around Toronto, coupled with sharply slowing residential development, has left the gap between population and the number of homes at an all-time high.

“The study shows that the gap between housing stock and population growth in the GTA is the widest it has been in over 50 years,” David Wilkes, president and CEO of BILD, said.

“This is a bright red warning light on the dashboard for all levels of government. Without bold steps, the housing crisis in the GTA is going to get far worse in the years ahead.”

The study found that as far back as 1972, the number of housing starts in Ontario has remained relatively constant, bouncing between around 50,000 and 100,000 per year

Population growth, on the other hand, has gone from the low hundred thousand range into the two hundred thousands and, more recently, closing in on half a million.

Ontario’s rapidly-growing population is something the government has repeatedly referenced as a reason to be aggressive in its push to build 1.5 million homes.

Get daily National news

“We remain focused on and committed to tackling Ontario’s housing supply crisis,” Housing Minister Paul Calandra said during a debate at Queen’s Park at the end of 2023.

“We can’t lose sight of the fact that Ontario’s population continues to grow at an unprecedented rate.”

Despite the province apparently being aware of the strain on Ontario’s housing supply, the BILD report suggests the development industry is grinding to a halt instead of speeding up.

Over the past two years, the number of housing applications submitted to local officials has fallen “significantly,” the report found.

- Flights, schools cancelled in GTA as Ontario winter storm wallops region

- ‘A year is a long time to wait’: Ontario speeds up cancer drug access

- American aquariums say they are working to provide future for Marineland’s belugas

- All options ‘on the table’ as Ontario looks to boost housing construction: finance minister

In 2021, a total of 2,482 applications were submitted to a sample of 14 GTA cities included in the report. The next year, that number dropped slightly to 2,187. And by 2023, it had fallen to 1,225.

Major developers across the industry are warning that those figures will get much worse before they get better — with presales for major projects slowing to a trickle, making financing new projects near impossible.

The Toronto Region Real Estate Board found that between April and June this year, condo sales across its area were down by 20 per cent compared to the previous year.

A summer report from Urbanation and CIBC Economics declared that Toronto’s condo market “is in a state of economic lockdown” with sales stopped.

The report found pre-sales sit well below 50 per cent of most construction projects, adding that without 70 per cent pre-sales projects can’t secure financing and begin construction

“Today’s sales are tomorrow’s housing starts — so we’re really going to see a dearth of supply in the market in two to three years when normally you’d see the construction happening for the sales that have taken place right now,” Wilkes previously told Global News.

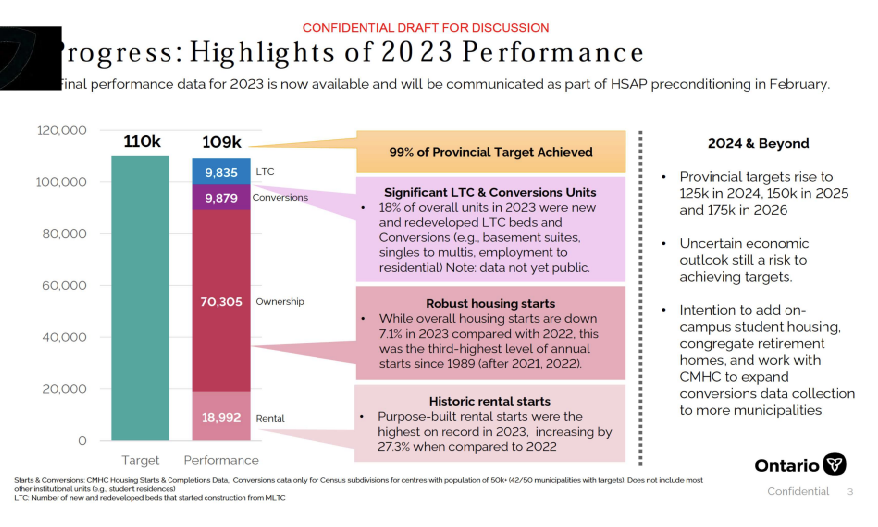

While housing starts in recent years have been high compared to historical averages, they have failed to hit the heights the Ford government needs to meet its self-imposed goal of 1.5 million new units by 2031.

Calandra has been accused of moving the goal posts by political opponents, adding long-term care beds and basement units to the tally for new housing starts. The government is also weighing throwing student residence and retirement homes into those figures.

In 2023, the government almost hit its own lower target of 110,000 new units — but will need to average 150,000 per year over a decade to make its own goal. The target for 2024 is 125,000.

Ontario NDP Leader Marit Stiles criticized the government’s current approach, suggesting relying on for-profit developers to solve the housing crisis through supply alone was unrealistic.

“We can’t wait for the private sector developers,” she said. “When will the conditions be right? When will they be perfect? The way to get started and kickstart building in this province is to get homes built through the province and not-for-profits and municipalities using public lands that is right there waiting to be used.”

The BILD report also found that development fees for homes in and around Toronto make up roughly 25 per cent of the cost of a new home, underlining a long-standing complaint from the development industry that taxes and fees are prohibitively high and driving up the cost of homes.

Municipalities, which collect the fees, have regularly countered with the phrase: “Growth must pay for growth.” Local officials have argued development fees — which fund sewers, roads and parks among other amenities — are necessary to ensure current residents don’t pay the cost of new housing.

The study commissioned by BILD found that, on average, municipal charges on low-rise developments like single-family homes rose by an average of $42,000 per unit over the past two years. The same fees increased by an average of $32,000 for high-rise units like condominiums.

According to the report, municipal fees add between $122,000 and $165,000 to the cost of a new home. Those fees, developers say, are passed directly onto consumers.

“To improve housing affordability, governments must act to accelerate approvals and reduce the overall tax burden they are placing on new home buyers,” Wilkes said.

“Without bold and immediate action, the region’s housing crisis will be exacerbated, leading to fewer housing starts, reduced jobs and compounded affordability issues in the years ahead.”

Comments