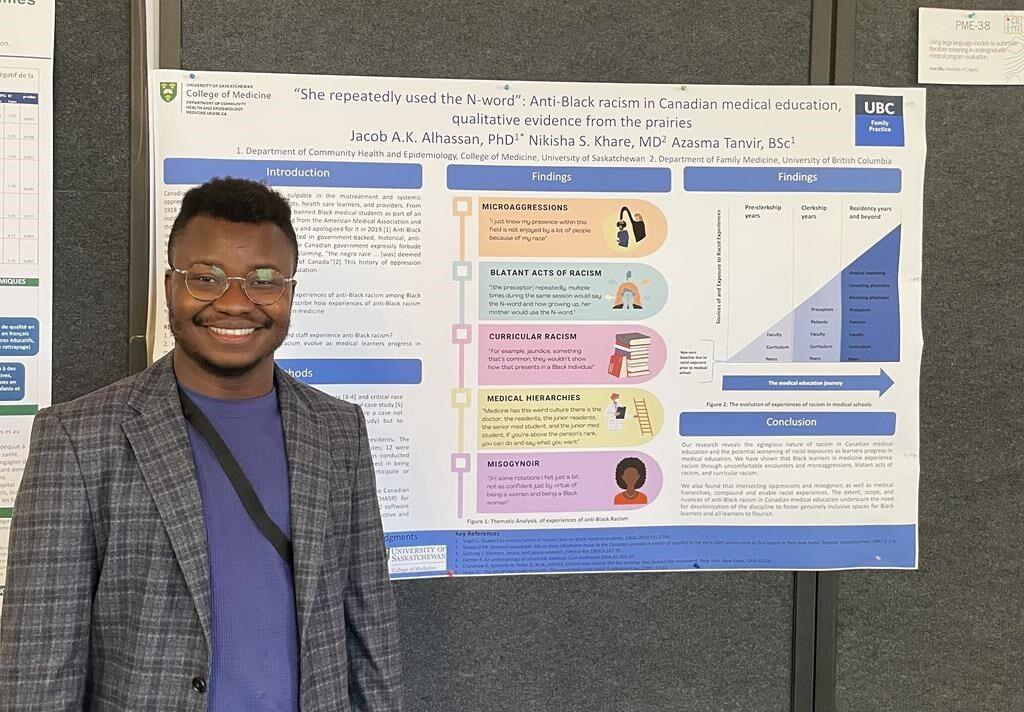

Medical researchers at the University of Saskatchewan’s college of medicine looked inward for their latest study — an attempt to capture the experiences of racism faced by Black medical school students.

The resulting empirical study, published Monday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, documents a litany of reported indignities that include a senior doctor defending her use of a racial slur, comments about police brutality against “dangerous” Black people in the United States, and scrutiny that left a student feeling like they did not belong.

Interviews were conducted between May and July 2022 with four Black residents and nine Black students at the Saskatoon university.

Lead author Jacob Alhassan, assistant professor of community health and epidemiology at the university, said it was important to document the experiences of Black students as well as residents who had completed their undergraduate training.

“Sometimes in the training arena for students, it’s assumed that things wouldn’t be that bad just because they are dealing with their professors,” said Alhassan, the only Black researcher on the study co-authored by two others.

“We ended up finding out that experiences of racism are not just between students and patients when students are in the clinical setting but from even their professors or clinicians that they are working with.”

A resident quoted in the study, which does not name any commenter or accused offender, says the doctor who used the slur supervised students and was also reported to have said people from a particular African country were “blacker than black, blacker than coal.”

“She repeatedly, multiple times, during the same session, would say the N-word,” said the resident, adding that the doctor seemed to feel entitled after mentioning that her parent, also a health-care professional, used the derogatory language in their home when she was growing up.

Get breaking National news

“‘Oh, it’s OK. I’m not racist,'” the resident remembered her saying.

Another student said they “feel vulnerable.”

“I just know my presence within this field is not enjoyed by a lot of people because of my race, you know? So, if there are just systems in place to protect the place of Black medical students within this field, then that would be sufficient, I think.”

While the study did not measure the mental health impact on students and residents, some said their confidence was shaken, especially if they were Black women who were unsure whether mistreatment was related to their gender, race or both.

Alhassan said that while some first-year students said they did not face any racism, learners generally identified specific cases of increasing racism as they progressed through their education and continued their training outside the classroom.

“They get racism from their preceptors, the patients, the faculty, the curriculum, the peers. And then by the time they’re in the residency years and beyond, the sources multiply further. They are getting it from hospital leadership, consulting physicians, attending physicians.”

While many workplaces have hierarchical structures, the pecking order is particularly defined in medicine among junior and senior students, and residents and physicians, he noted, adding that those who are Black often rank at the very bottom due to racism.

Some fear speaking out about their experience, Alhassan said.

“I’ve never interviewed a group of people who are so afraid that their responses could come back to affect them or harm them in one way or another,” he said.

“And I think that just tells you about the incredible sense of insecurity and lack of power that some of these students are experiencing because they’re afraid that something they say might come back and get them when they’re trying to get into residency.”

Marilyn Baetz, interim dean for a six-month term that expires at the end of June, said the university has made several changes since the study began two years ago, including work with the local chapter of the Black Medical Students Association of Canada.

Starting next spring, the admissions process will include Black representatives on interview panels, similar to policies at some other medical schools including the University of Toronto, the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary.

The curriculum will also continue to be more inclusive, said Baetz, noting that includes adding study material that shows how various types of diseases or skin conditions might look differently depending on skin colour.

The college is using an anti-racism program from New York’s Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to help guide curriculum changes and has developed equity, diversity and inclusion modules for students, staff and faculty, said Baetz, who returns to her role as vice-dean for faculty next month.

Baetz said the university does not collect race-based data on its students and faculty but is working with various demographic groups on respectful ways to gather that information.

The Saskatchewan research adds to a growing body of work examining the hurdles faced by Black medical students.

A qualitative study earlier this year by researchers from Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto medical school found few Black medical students pursue careers as surgeons in Canada due to factors including lack of mentorship, problematic admission criteria and racist microaggressions during training.

Another qualitative CMAJ study published in 2022 described systemic anti-Black racism as “deeply entrenched in health systems and all aspects of medical training.” It focused on the perspectives of Black medical students and senior faculty on school efforts to address anti-Black racism in 2020, finding that schools relied heavily on Black students to guide their responses in the absence of Black faculty.

Baetz said the Saskatchewan study “highlights concerns that I think are probably not different from other organizations.”

“But we at the university and at the college of medicine, in teaching our future health-care providers, our physicians and others, are committed to reconciliation.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.