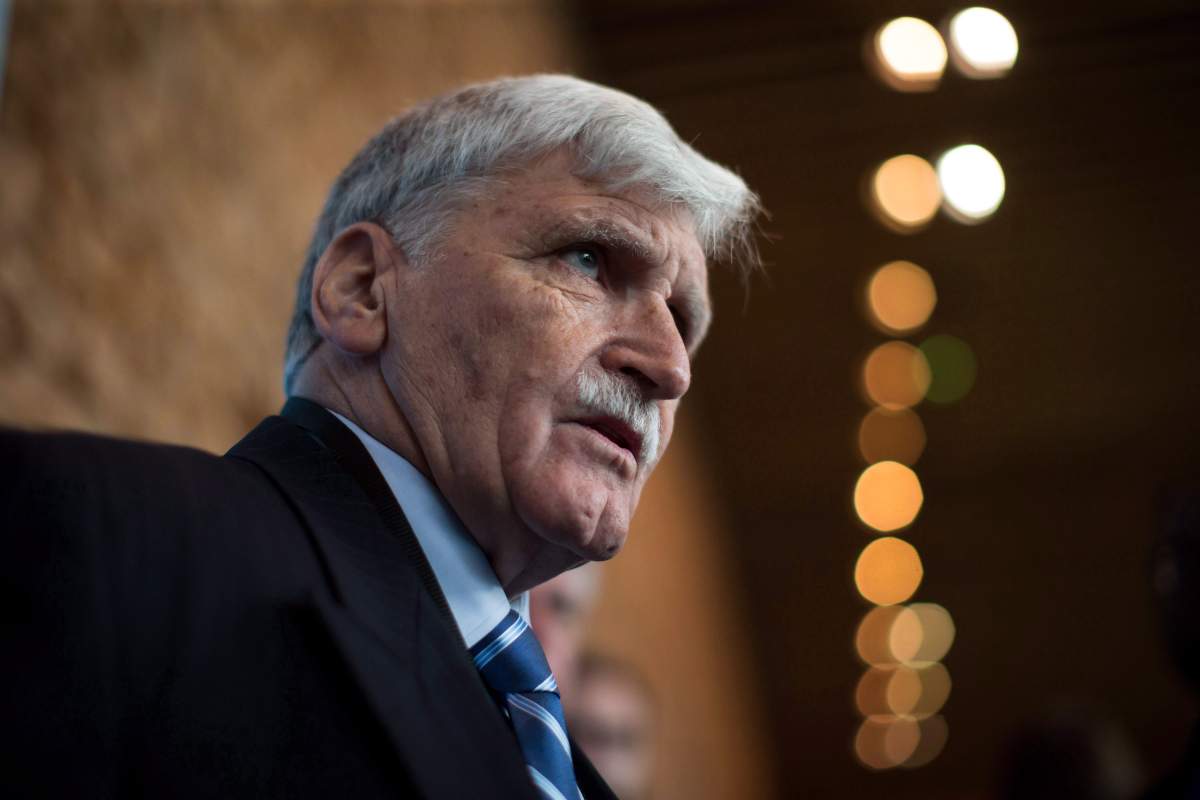

Three decades after the devastating Rwandan genocide, the retired Canadian general who led the United Nations peacekeeping mission that failed to stop the killings says he’s cautiously optimistic the world is moving toward a place where such brutality can never happen again.

But Romeo Dallaire, in an interview that aired Sunday on The West Block, told host Mercedes Stephenson he remains concerned about the continued presence of the genocide’s perpetrators and masterminds in Africa and around the world — including in Canada — who have not been brought to justice.

“Unless you bring justice throughout the process, you’re going to continue to have people who are getting away with it, and will nurture this (genocidal hatred) in the next generation,” he said. “And that’s the real concern.”

An estimated 800,000 Tutsi were killed by extremist Hutu in massacres that lasted over 100 days in 1994. Some moderate Hutu who tried to protect members of the Tutsi minority also were targeted and killed.

The genocide was ignited on April 6, 1994, when a plane carrying president Juvénal Habyarimana, a member of the majority Hutu, was shot down in the capital Kigali. The Tutsi were blamed for downing the plane and killing the president. Enraged, gangs of Hutu extremists began killing Tutsi and anyone who tried to protect them, backed by the army and police.

The Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by current President Paul Kagame, ultimately brought the genocide to an end and has ruled the country ever since. Many Hutu leaders, commanders and supporters fled the country into what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo as well as other parts of Africa, Europe, the United States and Canada.

Get daily National news

Tensions have been building between Rwanda and the Congo in recent months, with military buildups on the shared border and accusations between the two countries of supporting violent insurgents. Rwanda claims Hutu extremists have embedded themselves in the Congolese armed forces, while Congo accuses Rwanda of supporting M23, the largest rebel group behind the violence there.

Dallaire has called the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda that he led a “failure” for not being able to stop the genocide, largely due to interference from the United States and other U.N. Security Council members.

He says there is a “constant concern” that full-scale violence or even genocide could break out again on either side, as the underlying issues have not been fully resolved.

“There’s a constant acceptance that if we have a truce and we can work things out seemingly … then we will actually have peace,” he said. “But we haven’t reached that, we have never gotten to that depth.

“There’s always a nagging concern that there are (remaining) frictions that can in fact regenerate the problem — and all the more so, when we know that there’s activism to want to do that.”

Although critics accuse the authoritarian Kagame of crushing all dissent, he is also praised by many for presiding over relative peace and stability by trying to bridge ethnic divisions using legal means and other measures. The government imposed a tough penal code to punish genocide and outlaw the ideology behind it.

Since the 1994 genocide, Dallaire has testified at trials held around the world against perpetrators who have been hunted down and prosecuted for their role in the killings. Those include the 2007 trial of Desire Munyaneza in Montreal, which marked the first ever held under Canada’s Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act.

That trial, which lasted nearly two years, ultimately saw Munyaneza found guilty of multiple counts of genocide and war crimes and sentenced to life in prison in 2009. But Dallaire says he’s been told by Canadian officials that similar trials may not be held against other genocidaires in the country.

“The Justice Department kept telling me that we don’t have the money to be able to do the trials,” he said. “So these people are still living around.”

Despite those obstacles to justice and peace, Dallaire says he remains optimistic that the younger “post-genocide” generation in Rwanda and around the world will ultimately move the world away from conflict and brutality by mastering and maturing global communication.

“They’re what I call the generations without borders,” he said. “They see things in a grander scale of things, both the climate and humanity. And they feel that we can, in fact, thrive in the future and not simply continue on this road with nuclear weapons and so on, of just surviving.”

Dallaire added women should also be put into a position to greater influence the male-dominated institutions and governments that have led the world so far.

“Those two gangs together are going to change the face of humanity and move beyond just striving for truces, but actually looking for lasting peace,” he said.

Officials and members of the Rwandan diaspora in Canada marked the 30th anniversary of the genocide on Sunday with a march through Ottawa, followed by a commemorative ceremony.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.