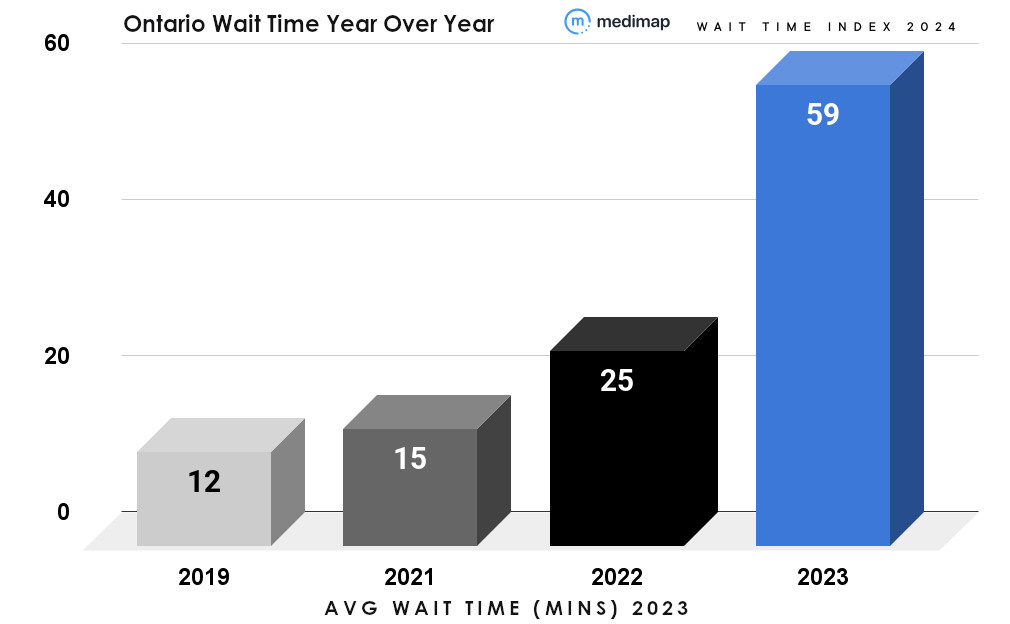

Despite having the second shortest wait times to see a doctor at a walk-in clinic across six provinces, the average Ontarian likely sat a half-hour longer to get treated last year.

Tech company Medimap, which connects patients with thousands of health-care clinics in several provinces, says 2023 data pulled from their platform suggests the average wait time is now about 59 minutes to see a physician compared to 2022.

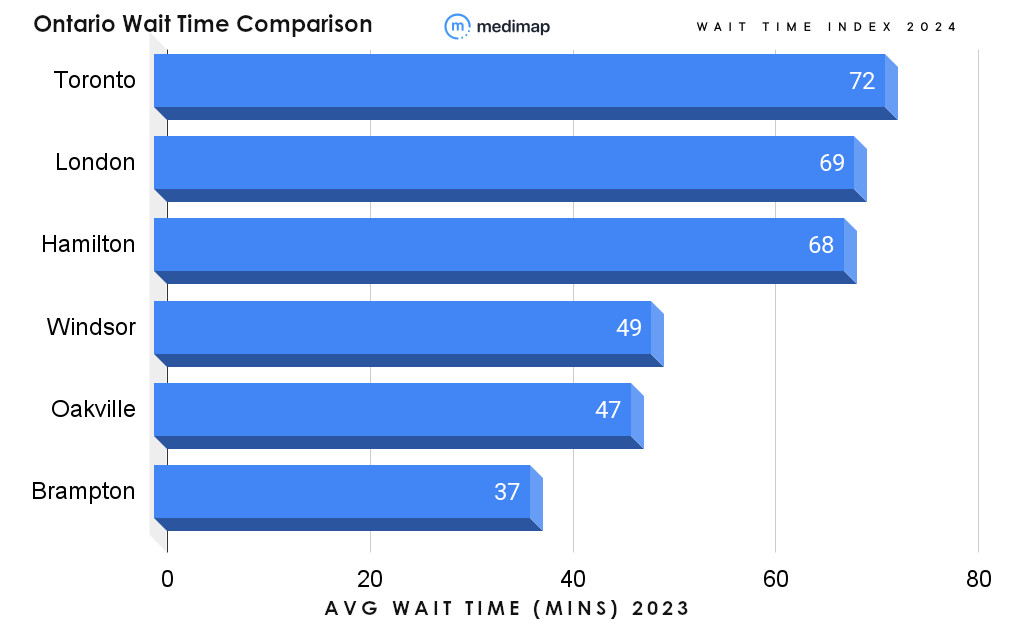

It’s an annual increase of 34 minutes on average across the province, with Torontonians cooling their heels in a clinic for around 72 minutes a visit, a Londoner sitting for 69 minutes and a Hamiltonian for 68.

Thomas Jankowski, the CEO of Medimap, says more than five years of analysis reveals “steady progression” in wait times with potential two- to three-hour stays during daily peak times across some of Canada’s major centres.

“There are some areas which stand out more than others … but generally speaking we’re looking at wait times of like 40 to 70 minutes across all of Ontario,” Jankowski explained.

“Some places are slightly better than others, like Brampton, just registering under 40 minutes which is one positive outlier.”

Jankowski says the data points to multiple issues on the “supply side” and believes it’s exacerbated by doctors retiring, young medical residents bypassing family medicine and more demand for health care due to retiring baby boomers and an influx of new Canadians coming to Ontario.

He says Hamilton is an interesting study since its wait times have been rising significantly in the last five years and now rivals much larger communities.

Get weekly health news

“So what we’re seeing here is there’s a lot of movement that’s interprovincial,” Jankowski said.

“People are leaving these bigger cities and moving into the more distant suburbs, so Hamilton has been seeing a lot of Toronto transplants moving here for the past few years.”

The OMA, which represents doctors in Ontario, says 2.3 million Ontarians were without a family doctor as of the end of January. By 2026, 4.4 million Ontarians are expected to be without a family doctor, or roughly one in four Ontarians.

Earlier this month, the chair of the Ontario Medical Association’s (OMA) general and family practice section submitted a move toward private health care in Ontario is “happening already” and that it’s “going to get worse.”

During a news conference on Feb. 15, Dr. David Barber said a shortage of family doctors in Ontario led to one of his own patients going to Montreal and paying about $2,000 for a test that had a roughly 12-month wait in Ontario.

“We are heading in that direction, there’s no doubt about it. We are heading towards the American model,” Barber suggested.

Last May, Ontario passed a health-reform bill that allows more private clinics to offer certain publicly-funded surgeries and procedures to draw some pressure off of the strained hospital community.

It included a January 2023 expansion that allowed pharmacists to prescribe treatments for 13 common conditions, including acid reflux, skin irritation, insect bites and sprains.

Jankowski says that recent increased scope for pharmacists is something prospective patients could take advantage of to limit clinical wait times.

“Something like 70,000 appointments were handled by pharmacists in the last year alone, and still so many people just don’t know about it,” he said.

“So if it’s a minor thing — cold sore, pinkeye, that sort of thing — you can be in and out in 15 minutes with a prescription in hand. Good luck seeing that in a walk-in.”

B.C. continues to have longest wait times at walk-in clinics

Of the six provinces Medimap tracks, walk-in clinics in Manitoba had the lowest wait times number with just 45 minutes on average.

British Columbia clocked in with the longest average wait times, about 93 minutes in 2023 — a 14-minute increase from 2022.

North Vancouver had the longest average wait times at 187 minutes.

B.C.’s health minister Adrian Dix weighed in on the recent Medimap numbers, cautioning the report is only a partial study.

It only operates in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia.

“It’s the people who are their clients and obviously in part is to promote their service,” Dix said.

“All of that is fine but the progress in British Columbia is something that the whole country is looking at.”

Medimap boasts connections to some 2000 health-care clinics across the country servicing about 12 million Canadians.

— with files from Amy Judd & Troy Charles

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.