The so-called ‘Ring of Fire’ in Ontario’s far north is expanding in size as mining claims spike in the area.

More than 31,000 mining claims have been registered to date, an increase of 28 per cent in a year, according to analysis by Wildlands League, a non-profit conservation group.

The rise in the number of mining claims coincides with more land being taken up by surface rights owners.

The claims now cover 626,000 hectares of the remote northern landscape, up 30 per cent from September 2022. The area is now nearly 10 times the size of the City of Toronto or double the Greater Sudbury area, the group says.

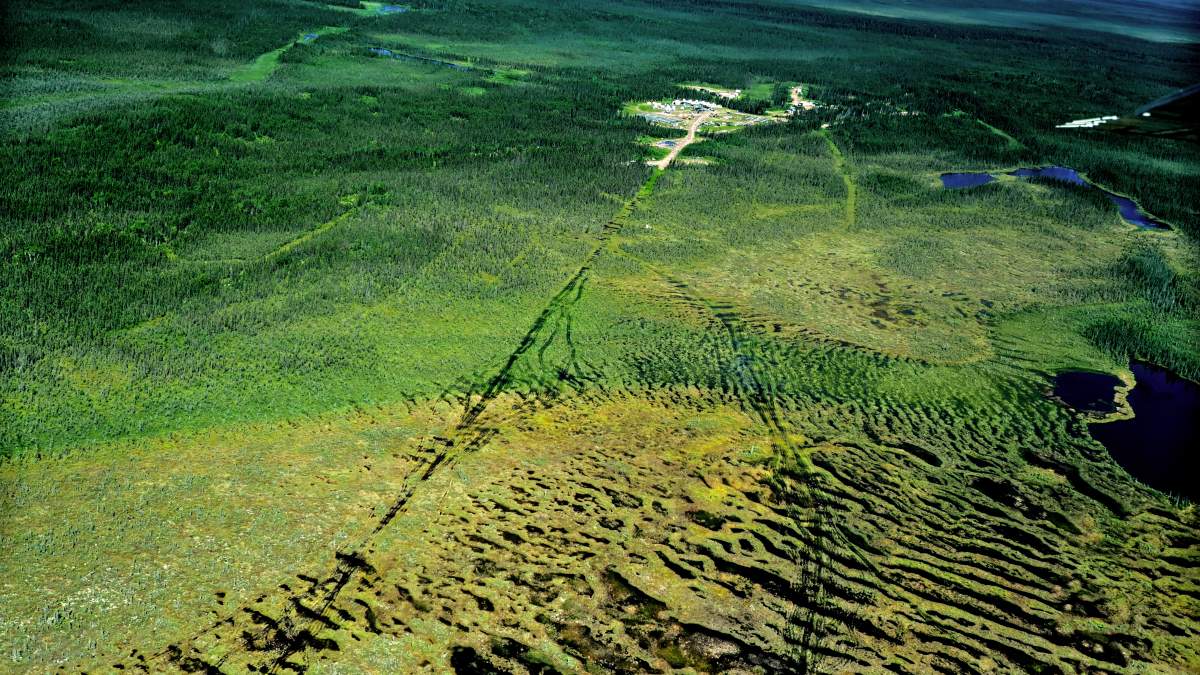

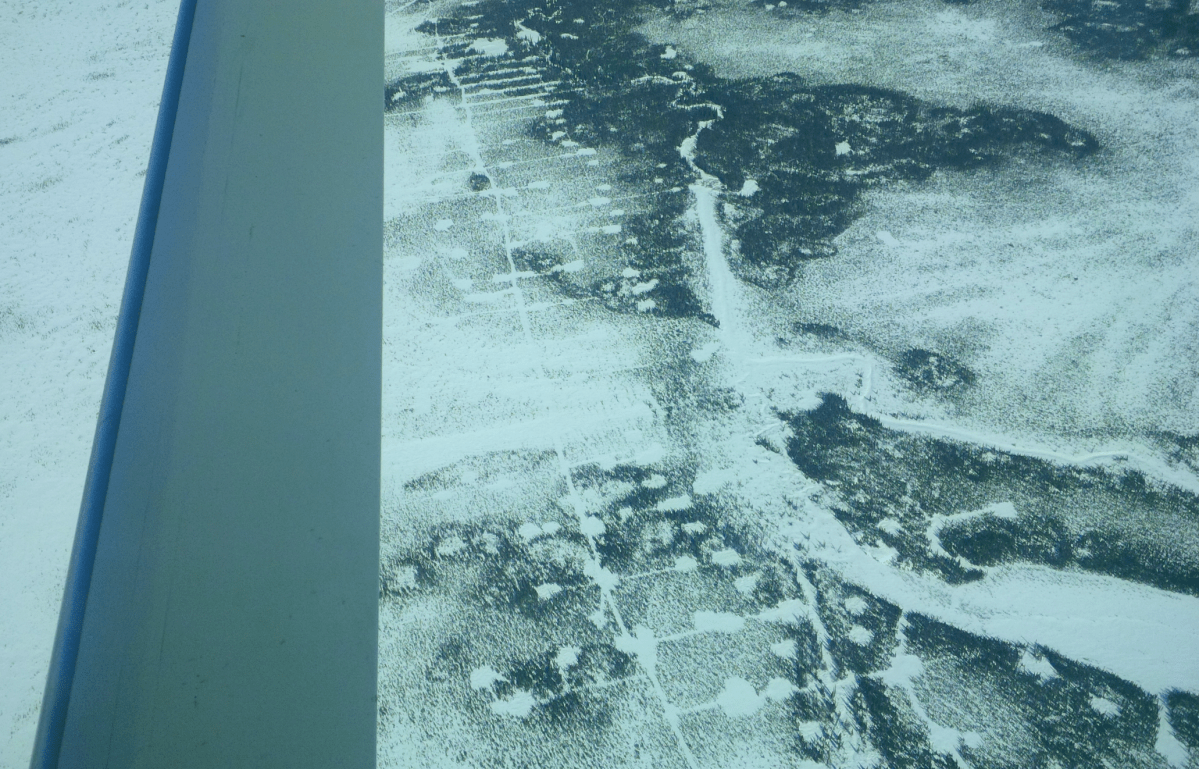

“I flew over the Ring of Fire again this summer and the footprint is sprawling,” said Janet Sumner, the executive director of Wildlands League.

The Ring of Fire is the name for circular mineral deposits located 540 kilometres north of Thunder Bay in the heart of Treaty 9 territory. The majority of the mining claims fall within a vast wetland called the Hudson Bay Lowlands. It contains the largest intact peatland expanse in North America and the second largest in the world, estimated to store more than 35 billion tonnes of carbon.

Chromite, copper, and nickel were discovered there in 2007, leading politicians to proclaim the site as Canada’s “next oil sands.”

But in the years since, the area has remained largely undeveloped, and evidence of the wealth of critical minerals underground unconfirmed. That has not stopped several mining companies from continuing to search for minerals and pressuring Ontario Premier Doug Ford to build a road network to open up the region to mining.

Juno Corp., a privately owned mining company based out of Toronto, is the largest claim holder in the Ring of Fire with more than 17,000 mining claims as of September 2023. Its claims alone cover approximately 333,000 hectares, according to data compiled by Wildlands League.

Ring of Fire Metals Ltd. is a close second with more than 10,600 claims. Ring of Fire Metals has been unified with its parent company, Wyloo, an Australian mining company. Juno Corp. and Wyloo did not respond to Global News’ interview requests by deadline.

The companies’ websites say, if extracted, the critical minerals will provide the raw materials needed to produce electric vehicle (EV) batteries in Ontario and other green technologies. The International Energy Agency predicts the demand for minerals will skyrocket over the next two decades, with nickel increasing by more than 60 per cent, and copper by 40 per cent.

But scientists warn that disturbing the peat soil on top of the deposits would do more harm to the global climate than EVs could solve.

Get breaking National news

“I’m worried the increase in mining claims will lead to more exploration activities within the region and that those exploration activities, which are largely unchecked, will lead to irreversible damage to the peatlands within the region,” says Lorna Harris, a peatlands scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society Canada.

Ontario uses the Mining Lands Administration System (MLAS), an electronic system whereby companies can stake claims online without physically going to the area or consulting any First Nations whose traditional lands the claim may fall within.

The system is designed to make people think that mining claims and exploration is low-impact but that is “Canadian fiction,” says Kate Kempton, a lawyer at Woodward & Co.

“As soon as a mining claim is recorded, it removes that land on which the whole claim is secured from First Nations abilities to have it turned into reserve lands or have it turned into a park—immediately,” she said.

Mining claims don’t always lead to further exploration activities, but they are the first step for companies wanting to acquire early exploration permits.

Those permits can allow companies to conduct activities like line cutting, whereby workers will cut a grid through a given area, removing trees and other vegetation in the process; mechanized surface stripping, which uses heavy equipment such as bulldozers, backhoes or excavators to remove soil from on top of the bedrock; drilling into the bedrock using large drill rigs to extract core samples.

If peatlands are drained, removed, or damaged in this way, they go from being a carbon sink to a carbon emitter. Harris estimates that if just half of the area covered by mining claims is disturbed, it would result in the release of more than one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide — one and half times Canada’s total reported greenhouse gas emissions in 2021.

The other risk, Harris says, is that extensive exploration activities could dry out areas of the peatlands, increasing the risk of ‘zombie fires.’

“When you get fires within peatlands, you get fires underground, which can smoulder over winter and ignite again in the following year,” Harris says. “We’re putting an absolutely enormous amount of carbon stored within those peatlands at risk.”

Under Ontario law, exploration companies must take certain actions after exploration activities, such as capping and sealing drill holes and stockpiling bedrock. There is no requirement to restore the lands to their previous condition, though companies may voluntarily do so.

The race to create an EV supply chain in Canada has renewed interest in the Ring of Fire minerals. Wyloo plans for its first mine, Eagle’s Nest, to focus on extracting high-grade nickel, but the company won’t say publicly what the deposit is valued at.

The region where all of this activity is taking place is exclusively occupied by Indigenous peoples. While two First Nations are working alongside the provincial government on the access roads that would lead to the Ring of Fire, ten other First Nations in the Treaty 9 territory have launched a lawsuit to change the way resource and land use decisions are made in the region.

“The case is premised on the fact that First Nations never agreed to hand over sole governance authority over the territory to the Crown. And so, this case is to take it back,” says Kempton, who represents the First Nations in the case.

If it is successful, Kempton says it would result in a complete overhaul of the system that allows companies to stake claims and conduct exploration activities with little say from First Nations. Rather, decisions would be made jointly by First Nations and various levels of government.

“This is a direct arrow at the heart of colonialism,” Kempton said.

For years now, several First Nations have fought for a seat at the decision-making table. In March, Neskantaga First Nation Chief Christopher Moonias shouted from the gallery of Queen’s Park that there would be no development in the Ring of Fire without the First Nations’ “free, prior and informed consent.”

During the exploration permitting process, First Nations will receive a letter notifying them of the exploration application. They then have 30 days to submit comments.

First Nations can apply for support in processing claims through the Ontario government’s Aboriginal Participation Fund, but are only eligible if the community is “experiencing high mineral exploration or development.”

The federal government has initiated a regional assessment for the Ring of Fire, designed to examine the cumulative impacts of opening up Ontario’s far north to development.

Earlier this year, Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change, committed to a co-led approach between the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada and First Nations who have traditional territory in the Ring of Fire region.

The process has been delayed due to disputes about which groups hold jurisdiction and what the terms of reference will be, such as the scope of the assessment. The terms of reference are expected to be released in early 2024.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify that Ring of Fire Metals has been unified with its parent company, Wyloo. An earlier version also included a quote claiming Ontario provides no support to First Nations responding to exploration permits. It has since been removed and a line has been added clarifying the province does have a program designed to do this. It also clarifies the obligations on the part of mining firms to rehabilitate lands. We regret the error.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.