He is one of the most influential philosophers of all time: François-Marie Arouet, more widely known by his pen name, Voltaire.

A French man from the Enlightenment period two centuries ago, he lived far away and in a long-gone era.

Despite that, you can now get closer to him through a rare collection of his manuscripts, now calling McGill University home.

The head of the Voltaire Foundation, Nicholas Cronk, deems it one of the greatest collections of Voltaire books and manuscripts in the world.

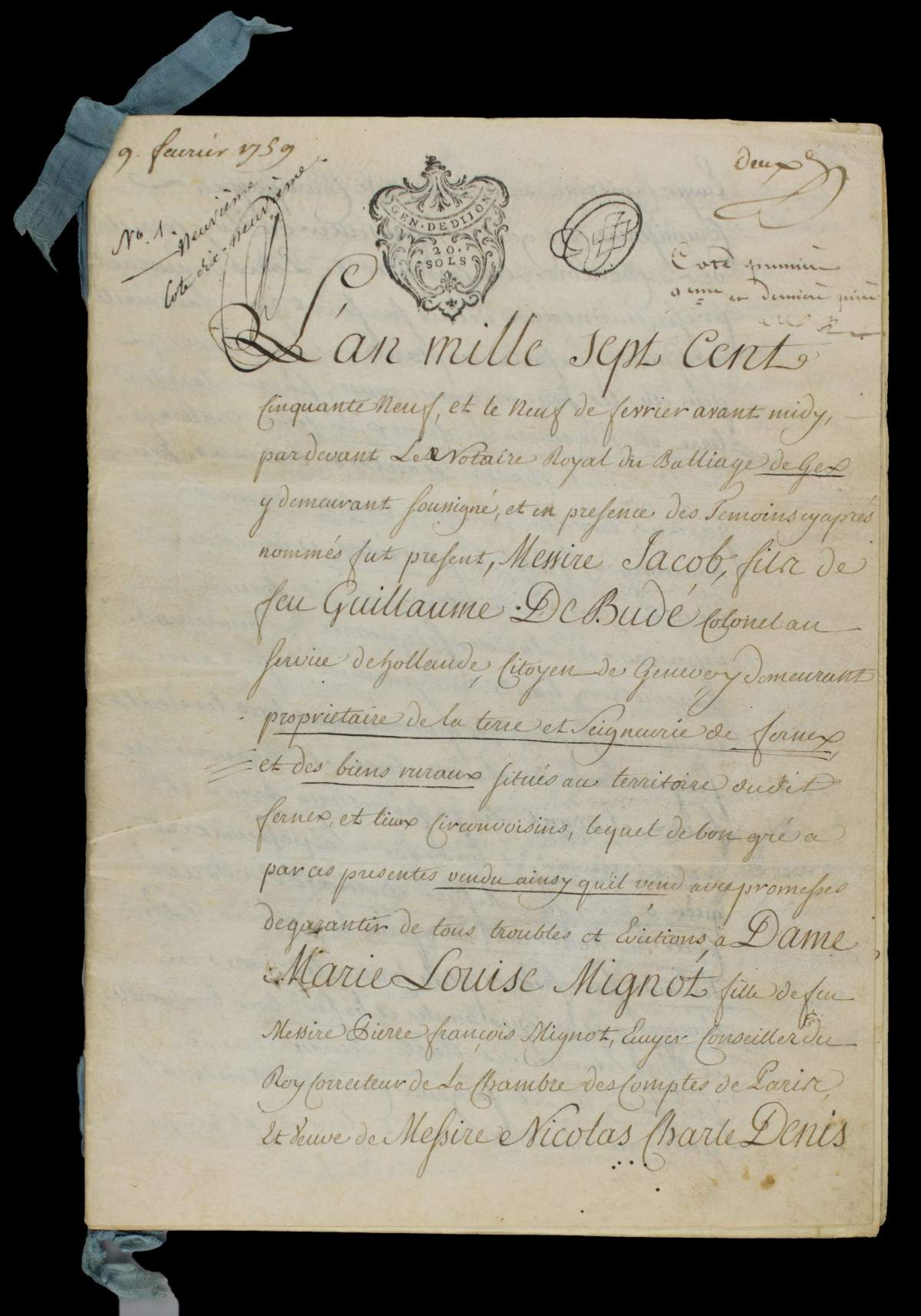

As you tour the collection, you will discover Voltaire’s inner musings, plastered on paper by his own hand, such as a letter to the king of Prussia telling him how sick he had been.

Voltaire was a popular and busy man who wrote to a lot of people.

“He had 1,800 correspondents,” said Ann Marie Holland, curator of the Enlightenment collections at McGill Rare Books and Special Collections.

Some of that correspondence was with women, including Émilie du Châtelet, a French philosopher and mathematician.

In one of the pages, Châtelet had placed big inky loops over Voltaire’s writing, as if she were trying to make it disappear.

“She actually ended up obliterating contents by Voltaire,” Holland said, as she showed correspondence between the two lovers.

Some of the philosopher’s content was so controversial it was banned.

Get breaking National news

His famous wit was infamously used to whip organized religion, a powerful institution at the time.

But Voltaire still found a way to spread his word clandestinely, by binding forbidden texts inside books that were allowed to circulate.

Many of the letters were written at his Chateau in Ferney, France near the border of Switzerland, where he was living in semi-exile.

The proximity to the border was deliberate in case he needed to flee.

Voltaire was able to purchase the estate after winning the Paris lottery. With financial freedom, he was able to focus on writing.

“He was actually writing feverishly at this moment,” Holland said.

Years later, the documents found in the chateau were handed to the new owners with a Canadian connection: the Lambert-David family, which includes McGill Prof. Peter Lambert-David Southam.

Four generations of the Lambert-David family would safeguard the documents, until Christopher Lyons, McGill’s associate dean of libraries, convinced Southam to let them go.

“And it’s wonderful, of course, because he could’ve sold this,” Lyons said. “The family were strong Voltarians. I think the fact that Peter Southam’s mother, Jacqueline Lambert-David, was really keen that the material come to Canada because she had married a Canadian, and the fact that Peter Southam himself was really concerned that it would go to a place where it could be used in research, that it had a life itself, was very much in keeping with the family’s belief in the material, in the message of the material, and what it held.”

Lyons said since McGill acquired the collection, phones have been ringing off the hook.

“The interest is global,” Lyons said. “That creates an opportunity. And we’ve had this with other collections, not only to have people come here to look at things, but then to meet each other and to bring researchers together.”

Researchers and curious folk of all kinds are able to see Voltaire’s body of work and related documents at McGill’s library.

“We’re literally a handshake away from Voltaire,” Holland said.

While you can’t literally shake his hand, you can, in a way, meet him through nearly 300 manuscripts and 1,500 pages of text, and become a little enlightened by one of history’s most important philosophers.

As Voltaire would sign off, ‘your most humble and most obeying servant.’

Comments