TORONTO – The Grand Canyon. Yellowstone. Yosemite.

Apollo?

If U.S. congresswomen Donna F. Edwards (D-MD) and Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) have their way, the next U.S. National Historical Park could very well be on the moon.

The proposal, put forth by the United States Committee on Science, Space, and Technology to protect the Apollo landing site is a discussion that has been going on for years.

“The charge to protect lunar artifacts goes back 10 years, 12 years now,” said anthropology professor Beth O’Leary from New Mexico State University who is serving as a consultant in the effort to protect the lunar artifacts. O’Leary calls herself a space archaeologist.

Spurred on by the Google Lunar X Prize, which offers a $30 million prize for a privately funded team to get robots to the moon, there is renewed interest in ensuring that the artifacts on the moon are preserved. One of the incentives of the Lunar X Prize is a “precision landing near an Apollo site or other lunar sites of interest.” And that is exactly what concerns historians like O’Leary.

NASA, is similarly concerned. In 2011, the agency released recommendations on how to protect the Apollo artifacts. It included a boundary that would stop any lunar dust from kicking up during the landing or ascent of another spacecraft (there is no wind on the moon to blow particles on the remaining artifacts). But they are merely recommendations and unenforceable.

Canadian space historian Randy Attwood said, “I think if there’s any way to preserve the areas and leave the material there, I certainly think they should do it. I just think it’s rather unenforceable.”

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (yes, that’s a real arm of the U.N.) drew up a document in 1967 entitled the “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.”

It was, of course, spawned during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union were in a space race. It was a real fear that one nation could set up a base on the moon, with missiles pointed at Earth and one country with dominance from above. Initially, it was only signed by the United States, the United Kingdom and the Russian Federation. But since then, a total of 102 countries have signed the resolution which was adopted by the UN General Assembly. One part of the document reads:

Article II

Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

Nowhere in the document does it say that one nation can’t set up a park. You see, that’s why the idea of a national park sits in a bit of a grey area.

In 1979, the UN drew up another treaty, this one more specific to the moon. The United States never signed that agreement (nor did Canada, though it’s not like we’re heading to the moon any time soon). In fact, only 15 nations have signed it (not ratified it), including new moon-faring country India. China, who is an emerging space superpower is also missing from the list of signatories.

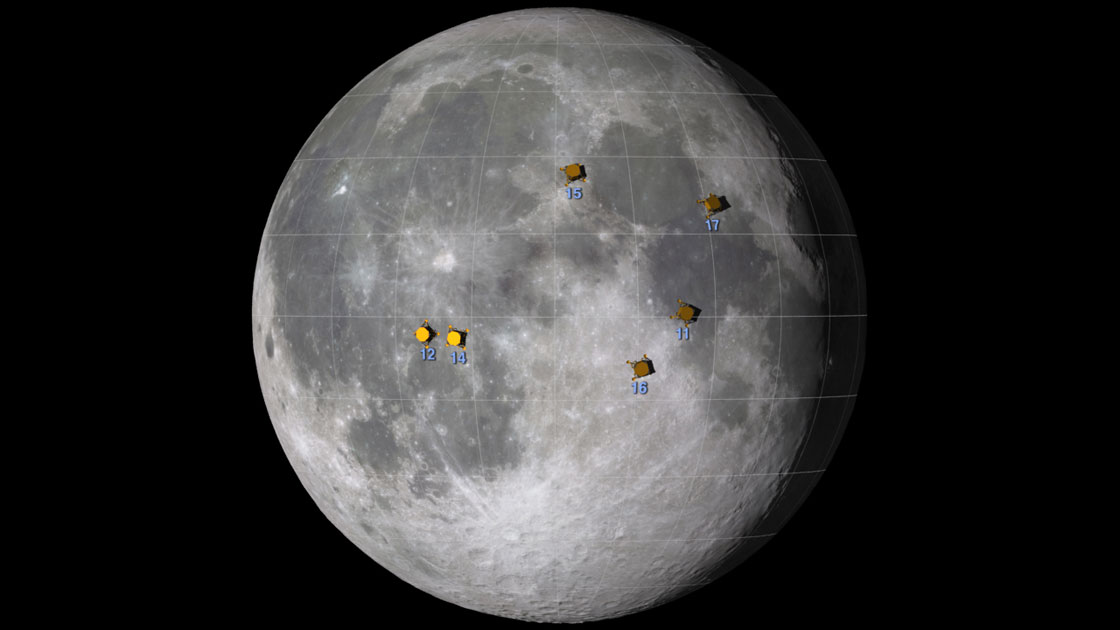

There is no doubt that the 106 artifacts (weighing a total of 110 metric tons) that remain on the moon – which includes boots, vehicles and other tools – belong to the United States. But a national park would set off boundaries, and boundaries speak to ownership.

O’Leary assured me that, to her, it’s more about human achievement.

“We’re still seeking ways in which to help protect this very important site that is less than 50 years old, using various avenues,” she said. “My whole approach, really, is that the U.S. landed there with people, the Russians put a lot of stuff up there, there are four other nations, but humanity owns the site. I mean, no one could have gotten there without the scientists and engineering and physicists from all over the world. So it’s a step for humanity.”

On the other side of the coin, why should any one country not be able to claim a part of the moon as their own? Free enterprise, and all that, right? When Jacques Cartier, Samuel de Champlain and Christopher Columbus went sailing off on their own, there weren’t other countries who told France or Spain that if they discovered a “new world,” they couldn’t have it.

Then again, the moon isn’t exactly “new.” But it is relatively unexplored.

The idea, of course, is that humanity has grown since the stockpiling of weapons and a race for superiority. The space race provided us with a previously unseen view of our planet – without borders or wars or divisions. It has, supposedly, opened our eyes to the fact that we are all one.

U.S. astronaut Frank Borman, who orbited the moon on the Apollo 8 mission in 1968 once said, “The view of the Earth from the Moon fascinated me – a small disk, 240,000 miles away… Raging nationalistic interests, famines, wars, pestilence, don’t show from that distance.”

What is needed is an international agreement to preserve the sites, especially Apollo 11. Nationalistic interests be damned. This is something that was achieved through the efforts of a planet. Despite the brilliance of American Robert Goddard, the U.S. would have fallen behind in the space race had they not swept up German Werner von Braun at the end of World War II.

No matter what the United States says, if they establish a National Park on the moon, there is no doubt that the rest of the world will feel that they own that part of the lunar surface. And what’s to stop Japan, China, or India from declaring their own parks? Or what about a private company? There can be the argument that a private company isn’t a nation and thereby doesn’t need to abide by the UN declaration.

It is a very slippery slope.

(Correction: An earlier version of this story identified Beth O’Leary as an archeology professor at the University of New Mexico.)

Comments