TORONTO – Imagine you are walking down a major street in your city; you see a unique event, such as a ten-car pile-up or a bank robbery unfolding in front of your eyes. What is your first instinct?

If you answered “take a photo” then you are a part of a social revolution – driven by social media and ever-improving handheld devices with high-quality cameras built in – in which anyone in the right place at the right time can become a news photographer.

From incidents like the deadly train derailment in Lac-Megantic, to the Boston Marathon bombing, many news events have been broken by everyday social media users who simply tweeted a photo.

In fact, it’s hard to remember the last time a cellphone camera wasn’t used to capture images of a breaking news event.

But it was almost 12 years ago, when terrorists attacked the Twin Towers on September 11th.

“The New York Times, Reuters, and The Associated Press, covered that story with their staff photojournalists and that’s why we have the most amazing photographs of that event,” recalled Jeffrey Dvorkin, Director of the Journalism Program at the University of Toronto.

“Since then, professional photojournalism has declined and citizen photography has increased.”

The shifting landscape of photography has even led some news organizations to restructure.

- ‘She has lost someone dear’: Professor hopes orca’s ‘grief swim’ spurs ethics rethink

- TikTok ban upheld by U.S. Supreme Court. Here’s what could happen next

- SpaceX Starship explodes over Caribbean, causing spectacular light show

- Massive temperature swing on the way for Alberta: ‘Coldest weather this winter’

The Chicago Sun-Times shocked some after laying off all of its photojournalists in May, leaving reporters to rely on their smartphones to gather images and video footage for their articles.

“The Chicago Sun-Times continues to evolve with our digitally savvy customers, and as a result, we have had to restructure the way we manage multimedia, including photography, across the network,” read a statement addressing the layoffs.

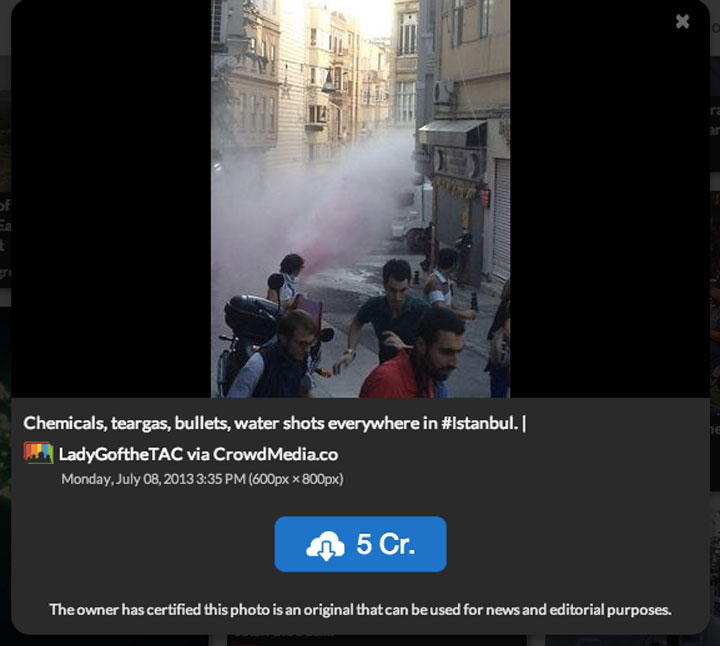

One Montreal-based crowd-sourcing startup is capitalizing on this evolution. CrowdMedia set out to create a business that helps media organizations find the best user-created images on social media, in a timely manner, keeping up with the world of breaking news.

Get breaking National news

CrowdMedia uses an automated platform that searches through over 150 million social photos per day, in real time, sorting out photos that are relevant to news stories. It then filters the results down to the 0.02 per cent that could be sold to the media for their newsworthiness.

The platform is designed to find images from users that news agencies may not be looking for, or able to find, whether it be on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook.

“What we are building is a way for our platform to detect automatically when something is happening somewhere and to send requests to get images from users automatically at that moment,” said CEO Martin Roldan, who noted the platform will become more automated as it develops.

And the company is already seeing success.

Just 15 minutes after the platform went live in June, shots rang out at Santa Monica College, close to where President Obama was making an appearance at a fundraiser. CrowdMedia secured the first images of the incident through eyewitnesses on Twitter and later found a broadcaster to publish them.

“Within less than an hour we had our proof of concept,” Roldan told Global News.

This, Roldan believes, is the evolution of photo and video journalism.

“Anyone who is there, who is first at the scene, has an advantage – and it doesn’t matter if you are good at it, if you happen to be there you have that edge,” said Roldan.

Quality over quantity, or vice versa

Though Dvorkin believes that citizen photo and video journalism will become increasingly important to mainstream media and describes it as “very healthy,” he cautions that there are still many dangers associated with user-created imagery.

“I think what we are seeing here is a new partnership that is being created between citizen journalists and traditional journalists,” Dvorkin told Global News.

“The citizen journalists will be out there – they will be taking pictures of the floods in Toronto, sharing them on their own websites, posting them on Instagram and Twitter feeds – and news organizations are going to have to figure out who is telling the truth.”

Dvorkin said that his main concern is the risk of digitally-manipulated or even digitally-created images.

“In a time where you can photoshop almost anything to hype and dramatize visuals, that is going to happen more frequently – unless there is some way that standards can be set for citizen photographers which will give them the credibility to send their images to mainstream media,” said Dvorkin.

He noted that there have even been instances of war zone photographers altering images to make it look as if air raids in Lebanon or bombings in Syria are worse than they are in order to gain a competitive edge in a highly-competitive freelance market.

And if professionals are willing to take the risk, amateurs will be too.

CrowdMedia is the first to admit that they are still improving their systems when it comes to authenticity.

Currently, the startup company authenticates photos through a mix of the location of the user versus the location of the event, using geo-coding in tweets for example, authenticating the type of camera used and the metadata of the image.

Another concern Dvorkin mentions is the quality of the images.

The journalism veteran describes this as a “decline in standards, but an expansion in content.”

He references some of the striking and haunting images taken during September 11th. Traditional digital SLR cameras, operated by trained photographers, have the ability to capture such images, while smartphone cameras – even with high megapixel counts – just don’t create the same effect.

“There is a difference in the quality. Does that matter as much as it used to? That’s another really interesting question, I think.”

Comments