CALGARY- An international panel co-chaired by Canadian experts is calling for change when it comes to dealing with concussions in sports.

In an updated consensus statement, about 30 doctors from around the world say that even the most advanced protective equipment, such as helmets and mouth guards, don’t necessarily prevent a concussion.

“This is not to downplay the importance of protective equipment,” co-chair Dr. Willem Meeuwisse told Global News.

“What is not true is that helmets and mouth guards prevent concussion because what we are talking about is the shaking of the brain inside a hard skull. Putting more padding around the hard skull may not reduce the amount of brain movement . . . it might increase it in some cases,” he said.

Meeuwisse leads the University of Calgary’s Brain Injury Initiative. He and his colleagues collaborated with counterparts from the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and Scandinavian countries for their research.

Their new guidelines, updated for the fourth time since they were first issued in 2001, also offers advice on how to diagnose and treat concussion during recovery.

A report reflecting the views of leading sport concussion researchers was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine on Monday, along with the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine and a number of other leading medical journals. The research is backed by the International Olympic Committee, FIFA, the International Rugby Board and other sports organizations.

Meeuwisse told Global News he hopes the guidelines will be translated into different languages and distributed widely. It’s meant to help health care workers and coaches alike in identifying concussion, treating the injury and managing the recovery process.

- B.C. to ban drug use in all public places in major overhaul of decriminalization

- 3 women diagnosed with HIV after ‘vampire facials’ at unlicensed U.S. spa

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

- ‘Super lice’ are becoming more resistant to chemical shampoos. What to use instead

Concussion a grave injury in sports

The brain injury can have devastating long-term consequences, such as memory loss or recurring headaches-something Calgary’s Kery MacDonald is all too familiar with.

Eight years ago, MacDonald experienced his first concussion.

“I was playing men’s league soccer, and basically went up to head a ball at the same time as an opponent, and our heads collided,” he remembers.

MacDonald was knocked unconscious, and experienced debilitating side effects for months.

“This is seen very much as an evolving injury, when you think about an athlete getting injured on the playing field, the injury changes over time,” Meeuwisse explained.

Athletes need to disclose their condition, experts say

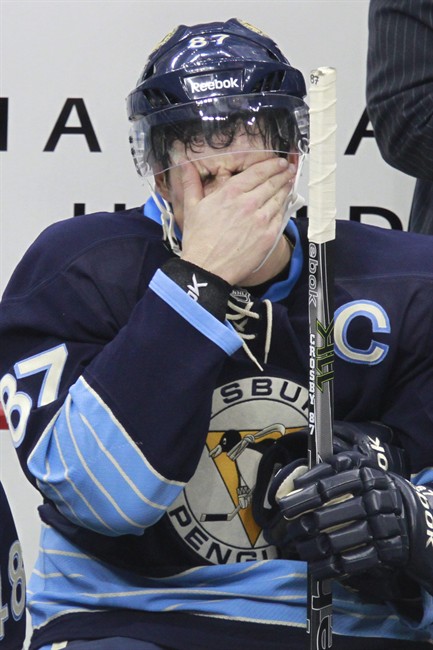

Players may be hesitant to admit the severity of their symptoms, too, Meeuwisse adds. He’s both a researcher and a clinician so he sees patients first-hand.

This is risky because evidence has shown that a first concussion can make you vulnerable to severe second or third brain injuries.

These updated guidelines come at a pivotal time in contact sports, according to Bob Stellick, who has worked in the hockey world for the past 30 years.

He notes that there is pressure on players and their coaches to get them back in the game.

“In all professional sports there’s always been a challenge as far as pushing guys back from injury. There’s money on the line in pro sports,” he explained.

But this is balancing out as officials prioritize health over entertainment. The NHL and NFL, for example, have poured resources and funding into studying head injuries and how to prevent them in sports.

“They’re nervous about this now compared to the past and they’re very aware that they’ve got to make progress,” he told Global News.

Stellick was director of business operations for the Toronto Maple Leafs for more than a decade and now owns a sports marketing consultancy company.

Players feel this innate pressure to perform, though, especially if they’re on the bubble.

“Guys who are on the bubble need to get back in the lineup. No one wants, in any sport, to be called the injury-prone guy, the guy who is made out of glass,” he said.

Recovery time changes from athlete to athlete

While most athletes recover within seven to 10 days, rest alone may not be enough to help all patients heal.

“If 80 per cent are better in 10 days, then 20 per cent are not,” Meeuwisse says. “What do you do with 20 per cent of people? Four years ago when we met, the principal was more rest, and now we recognize that probably isn’t ideal.”

Instead, athletes suffering from concussion could ease into other responsibilities, such as returning to school or taking on some light exercise, for example. This contradicts previous advice that recommended bed rest for the most part.

Athletes should receive medical clearance from a doctor before they return to their sport, though.

“The diagnosis and management of the injury still is an individual clinical decision because no two concussions are exactly the same,” Meeuwisse said.

Meeuwisse adds that instead of relying on protective gear, coaches need to learn how to better recognize concussions, and pull injured players from games immediately.

The panel finds the key is to ensure athletes are given enough time and the right forms of therapy, so the brain can fully recover. Click here to view the report in its entirety.

With files from Heather Yourex

Comments