The boomer generation has started to hit retirement age, and economists are running for cover.

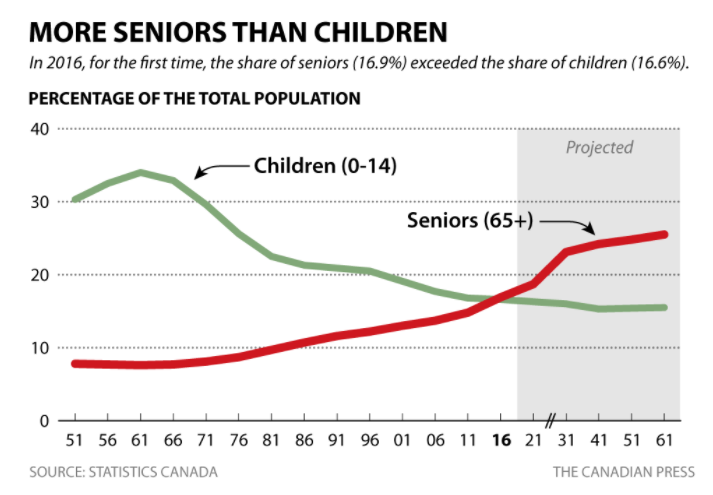

In Canada for the first time since record-keeping began, there were more seniors than children in 2016, census data recently revealed. The consequences will be dire, analysts have warned, from slower economic growth to ballooning healthcare costs.

READ MORE: Census 2016: For the 1st time, more seniors than children living in Canada

But the grey tsunami that’s washing over most advanced economies could have another much less talked-about impact: It could become a major obstacle on the path to financial equality between men and women.

Women still do most of the caregiving

Caring for ageing parents costs Canadians $33 billion annually, according to CIBC. And women are still bearing the brunt of the caregiving work in this country, a number of Canadian studies report.

Much has been said about how maternity and child rearing holds back working women, who are more likely to take time off work and miss out on promotions to start a family.

But with the share of children projected to keep declining and the ranks of old folks set to balloon, looking after the elderly will inevitably become a larger part of the caregiving load.

And having older family members who are no longer self-sufficient “absolutely affects women more,” said Ilana Schonwetter, an investment advisor at Blueshore Financial.

Sisters are generally more likely than brothers to care for elderly parents.

But even daughters-in-law are more likely than sons to be the caregiver in charge, according to Schonwetter’s experience with clients.

READ MORE: Here’s what Canadian women would be making in these jobs if they were men

A recent CIBC poll found that women are spending an average of 10 hours a week aiding aging parents, compared to less than eight hours reported by men.

And Canadian women aged 45 and older reported having spent almost six years providing care for infirm or elderly family members throughout their lives, compared with less than three-and-a-half years for men, according to a 2015 study by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP).

The paper also noted that women were more likely to be performing “traditionally female” tasks — like cleaning, cooking and providing personal and medical care — that are typically less compatible with work schedules.

READ MORE: Single women play down their ambition to attract men, new study finds

The financial impact of caregiving

The impact on women’s finances is significant, said Schonwetter.

The aggregate wage loss due to missing work, reducing hours and leaving employment entirely stood at $221 million annually for women between 2003 and 2008, according to IRPP. For men, it stood at $116 million.

READ MORE: In an aging Canada, women need to save more than men — even if they make less

Also, women are often forced to stop working at a younger age in order to take care of infirm older relatives, Schonwetter told Global News.

Early retirement not only “shaves off a few years worth of savings,” she noted, but also means women have to start tapping their nest egg sooner.

READ MORE: Boomers are the winners in Canada’s labour market, April jobs report shows

In general, almost 30 per cent of working Canadians with parents over the age of 65 report having to take time off the job. The aggregate tally is a loss of 450 working hours per year, equivalent to $27 billion in foregone earnings or sacrificed vacation time, according to CIBC.

“And that doesn’t even take into account the reduced potential for job mobility or promotion that could be associated with taking that amount of time off from work,” writes CIBC economists Benjamin Tal and Royce Mendes.

Canada’s caregivers also incur out-of-pocket costs, which amount to $3,300 annually per caregiver, Tal and Mendes estimate.

READ MORE: Time to stop shaming millennials for living with their parents, personal finance experts say

What women can do

Women need to act before caregiving becomes “a crushing burden of everyday life,” Carolyn Rosenblatt, a California-based elder law attorney, wrote in Forbes.

The first step is to ask male siblings to take up a larger share of the load, Rosenblatt argued.

“They also need to educate their siblings about the personal financial impact on them of doing the caregiver job. It’s not free when you’re losing money doing it.”

The same arguably holds for women who are expected to take the lead in caring for their in-laws as well.

But that’s not enough. Women also need to be specific about how caregiving tasks should be divided, noted Rosenblatt.

With the share of Canadians aged 65 and older set to rise from 17 per cent to 22 per cent over the next decade, this may well be the next frontier in the struggle for gender pay equality.

Comments