TORONTO – How does education in Canada compare to other countries around the world? The answer, according to a benchmark international testing program, is very well.

But what can we learn from the countries who are outperforming us?

The test used to compare students from different countries is called the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and was developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA tests reading, math and science, and has emphasized one of the three domains each time it’s been administered (every three years, starting in 2000). The 2012 results are yet to be published.

What the PISA test does (and doesn’t do)

In 2009, approximately 23,000 Canadian 15-year-olds from about 1,000 schools participated across the 10 provinces in both English and French school systems. Sixty-five countries participated in the program in total, though Shanghai and Hong Kong were counted as separate samples, despite both being in China.

Canada ranked sixth in reading, eighth in science and tenth in math.

Two countries that consistently outperform Canada in all three areas are China (specifically Shanghai’s results were reported) and Finland. So what are educators in these countries doing that might explain the high test scores?

Shanghai, China

A 2010 OECD report says teaching and learning in China has been “very much oriented toward exam preparation.” Music, art and sometimes physical education have been removed from student timetables because they aren’t covered in public exams.

Instead of extracurricular activities, students in Shanghai were working long hours and studying into the weekends, mainly for exam preparation. About four out of five Shanghai children attend after-school tutorial groups to help prepare, according to the OECD.

Dr. Yong Zhao, an education professor at the University of Oregon and director of the US-China Center for Research on Educational Excellence, says that the stereotype of Asian children studying all the time is often true.

“If you spend all the time doing something, and the whole system geared towards making sure you learn all the academics,” says Zhao. “It really has to do with having a society make academic achievement the only criteria, the only catalyst towards social mobility.”

Caution to Canadians: Why Chinese educators worry about high PISA scores

But another Chinese initiative that has caught educators’ attention and garnered positive results is emphasizing teacher training by matching teachers from the strongest-performing schools to teachers in schools that are weaker.

Watch a video about this initiative used in Shanghai, called ‘Empowered Administration,’ here.

One middle school-considered to be the worst performing school in its district-reported “only” 89 per cent of students achieving the standard needed to continue to high school in 2005. After the Empowered Administration program, the school reached 100 per cent in 2010.

Ben Levin is the Canada Research Chair in Education Leadership and Policy at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, and previously served as Deputy Minister of Education in both Ontario (2004-2007; 2008-2009) and Manitoba (1999-2002). He says Shanghai’s efforts to move strong teachers into the highest challenged schools is indicative of a positive approach to education.

Finland

Finland is another top-scoring country that maintains a positive approach to education. But in contrast with Shanghai’s competitive testing and additional hours of academic work, Finland uses a child-centred approach.

Senior advisor at Finland’s Ministry of Education Tommi Karjalainen describes the amount of homework assigned to Finnish children as “not so much” in an email to Globalnews.ca.

There is no testing in primary school, a free hot meal is given to students daily, and according to world-renowned Finnish education expert Pasi Sahlberg, they aim to fund schools according to their needs.

Teachers are given lots of autonomy over the curriculum-board authorities don’t even visit to inspect classrooms.

Perhaps this is because the profession is so well respected in Finnish society, possibly linked to the fact that all primary school teachers have master’s degrees. More than 10 people apply to be primary-school teachers for each spot open in university, which Sahlberg says is more difficult than getting into medicine.

Other notable numbers are that the number of private schools in the Scandinavian country is below two per cent, which is the same percentage of students who repeat grades. Over 96 per cent of high school grads continue into upper secondary-level schools, and the level of adult literacy is 100 per cent, according to Karjalainen.

Empowering teachers

So the two countries that seem on opposite ends of the spectrum when it comes to emphasis on exams, score very similarly on the PISA test. What they have in common seems to be trust in teachers and collaboration between schools to make sure everyone gets what they need to facilitate student learning.

So what has Canada learned from PISA?

University of British Columbia professor Charles Ungerleider, the director of research and managing partner at Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group who previously worked on a government team analyzing PISA results, believes the reason Canada is improving is largely because of teachers.

“Canada, generally speaking, has well-prepared and well-educated teachers. And if you had to put your finger on a single thing that makes a difference in the lives of students, teachers and teacher quality is pivotally important.”

Ungerleider says over the past 40 years, Canada has improved by “virtually any measure you can think of” such as better graduation rates, more students taking more demanding courses and more students going on to post-secondary education.

He mentions provinces like Ontario, where there was a value shift on the part of schools to being more student-oriented rather than system-oriented, encouraging staff to reach out to students and intervene early with students who are at risk of not succeeding.

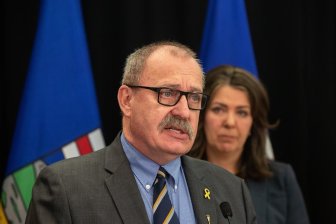

In Alberta, Canada’s highest performing province on the 2009 PISA reading and science sections, the Alberta Initiative for School Improvement (AISI) grant is given to school boards to use at their discretion, and projects are shared among a provincial committee.

“The idea is to get innovative and think outside the box,” says president of the Alberta School Boards Association Jacquie Hansen in an email to Globalnews.ca. “Many schools zeroed in on an achievement gap, like numeracy or literacy and spent all the money on new initiatives focused of these things. Others used it for technology, others high school completion.”

When it comes to staying in school, Ungerleider says regardless of structural changes to the system, the most important thing is the quality of teaching and student engagement.

“Teachers working with each other, watching each other teach, trying out new ideas that are well-grounded in research and then seeing how they work in their school,” adds Levin. “Building a sense of team among teachers…all that kind of stuff has to be built to create a really high quality school and school system.”

So while there’s always room for improvement, Canadians should be proud of student achievement on the PISA tests.

And don’t forget, Canadian students are among the highest ranking participants in the OECD nations. Dozens of delegates from other countries have visited Canada to ask what it is that we are doing here to enjoy such success.

Read about what other countries are learning from Canadian educators here.

Comments