In February, the Ontario government announced it planned to introduce legislation aimed at helping first responders with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The proposed legislation would make PTSD a presumed work-related injury among emergency workers: meaning that such workers would no longer have to prove that their PTSD was because of their job. Ontario is following Alberta and Manitoba in introducing such presumptive legislation.

READ MORE: Ontario launches plan to help first responders deal with PTSD

It’s an important change, said Vince Savoia, executive director of the Tema Conter Memorial Trust, an organization dedicated to addressing mental health among first responders and the military. The law is also addressing a big problem.

Eleven first responders have committed suicide since Jan. 1, he said. Paramedics commit suicide at a rate almost twice that of the rest of the male population: 44 per 100,000 people.

Alberta’s Workers’ Compensation Board accepted 54 PTSD claims from first responders in 2015, and an additional 112 claims for other types of psychological injuries.

READ MORE: ‘I went to hell’: Raising awareness of PTSD among police officers, one haircut at a time

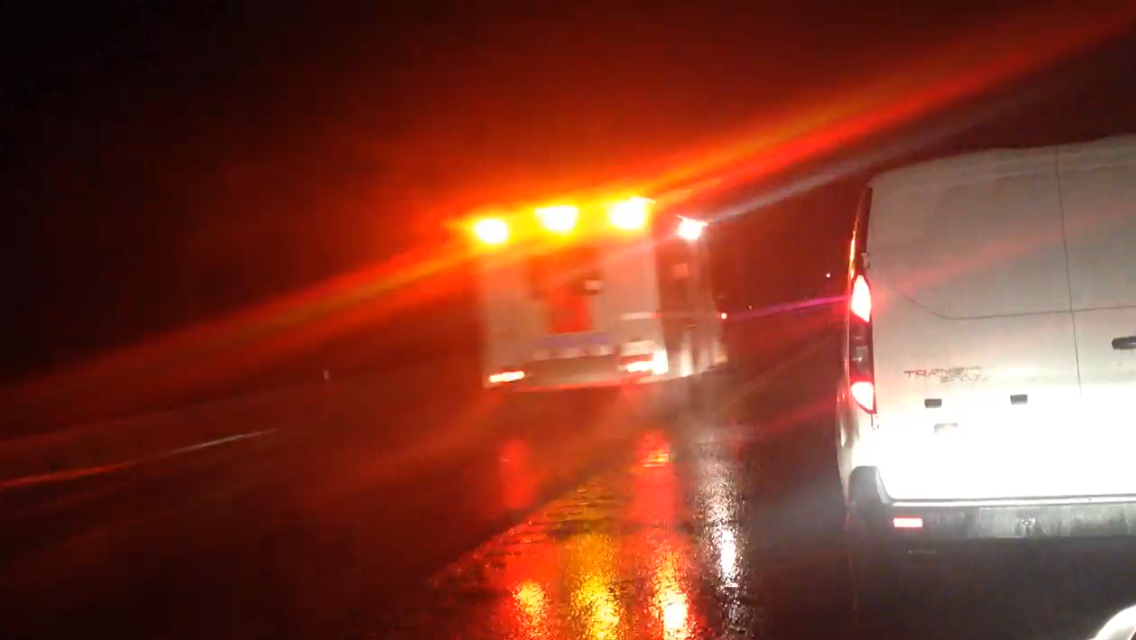

Emergency workers face a lot of stress – and their unique situation has gotten a lot of attention recently. Global News and other media organizations have reported extensively on the high rates of PTSD and suicide among first responders.

But, presumptive legislation is just one step, said Savoia. First responders also need the workplace culture to change and to have support available to them before they get to the point of developing PTSD.

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

‘John Wayne’ syndrome

Bob Geilen started to notice that he was acting differently after he visited the Philippines.

The London, Ontario firefighter had been volunteering, helping to clean up after Typhoon Haiyan.

“I witnessed something that was completely horrifying, and it kind of sent me over the edge, and when I got back from what I was doing, my personality had changed, very dark thoughts. I wasn’t myself.”

The stresses from his job had built up over time, but it was the sight of a dog, carrying a baby’s arm, that hit him. “That’s what it was eating. That’s what set me off. Horrendous,” he said. He still has trouble talking about it.

He found himself alienating his friends and family, and focusing totally on his job. Ultimately, his friends helped him and he saw a psychiatrist before things got much worse.

Geilen wants emergency workers like him to know that there is help out there: that’s why he appeared alongside several colleagues in a video produced for the London Fire Service, in which firefighters talk about the difficulties of the job and how to deal with the stress. Acknowledging that stress and talking about it is a big step for many first responders.

READ MORE: ‘I was scared of appearing weak’: First responders speak out on PTSD

And it is a difficult job.

Doug Kunihiro, a paramedic with 25 years’ experience and an instructor at Centennial College, says that the world many emergency workers inhabit is very different from what most people see.

“The average person will never hold a child in their hands as the child is dying,” he said.

“Most people will never witness a homicide first hand. Most people will never touch someone who has died by homicide. Most people will never see a suicide completed.”

For Kunihiro, the biggest thing that needs changing is the macho culture among first responders.

“In my generation of paramedic, we did not talk about calls that bothered us. We did not admit that calls bothered us. We did not tell anyone when we had symptoms of potential critical incident stress,” he said.

Savoia calls it the “John Wayne” syndrome: where the answer to a problem is to, “Suck it up, Buttercup.”

Firefighters are much the same, according to Geilen.

“They see so much, but the old way was ‘Suck it up, go have a drink, get out there and let’s do it again,’” he said.

Kunihiro tries to teach his students to take a different view.

Although they come into the program with very little idea of what the job entails, he encourages them to talk about negative experiences they might have during their work placement.

“We open it up to them and say, ‘It is okay to talk about what has happened to you. It is okay to go home after a call before the end of your shift. It is okay to take a day off when you’re still thinking about a troubling call and you’re not ready to do another one. That’s okay.’”

A critical incident stress team, comprised of students, himself, and a mental health professional is on hand to help students deal with traumatic events. And it’s paying off.

“They are doing much better than my generation of paramedic is doing,” he said. He’s hopeful that these students will go on to change their respective workplaces. He’s seen students who were on the school’s critical incident stress team join similar groups in their paramedic jobs.

The culture in the workplace is starting to change, he said. But, “Culture doesn’t change overnight and that’s part of the challenge.”

And culture isn’t everything. “Beyond attitude and stigma, there also have to be support services in place.”

Providing the services

“It’s great that we’re raising all this awareness,” said Savoia. “But when people do come forward, the resources aren’t there to help them.”

Peer support is helpful, he said, but many people lack the training needed to be really effective. So, they should focus on referring people to trained mental health professionals as needed.

What he would really like is to have those mental health professionals covered by OHIP and other provincial insurance plans. “You can walk into the hospital with a broken leg and you’ll be treated and you won’t pay a dime, but God forbid you want to see a psychologist. That will cost you a pretty penny to see one,” he said.

According to CAMH, psychiatrists are currently covered by OHIP, but outside of a hospital setting, other mental health professionals such as psychologists, counsellors, and therapists are generally not covered.

He’s hoping that at some point soon, first responders can get the help they need, and aren’t afraid to ask for it.

“I think the day when a first responder can step forward and say, ‘I’m struggling and I need help,’ and he or she is immediately referred to the proper mental health professional and they get the support that they need without having to worry about the financial consequences of getting that support, that will be a good day.”

Comments