Apple’s refusal to comply with a court order asking the tech giant to help the FBI hack an iPhone belonging to one of the San Bernardino, Ca., shooters has stirred up much debate and sparked many questions.

But one of the most common questions being asked seems to be the simplest: why can’t the FBI hack an iPhone without help from Apple?

It all comes down to one simple privacy setting included on every iPhone Apple makes. And, thanks to the way Apple has designed its software, it prevents even the FBI’s top security investigators from accessing data stored on one of the most-used consumer devices on the market.

READ MORE: What Apple’s opposition to phone hacking says about its dedication to privacy

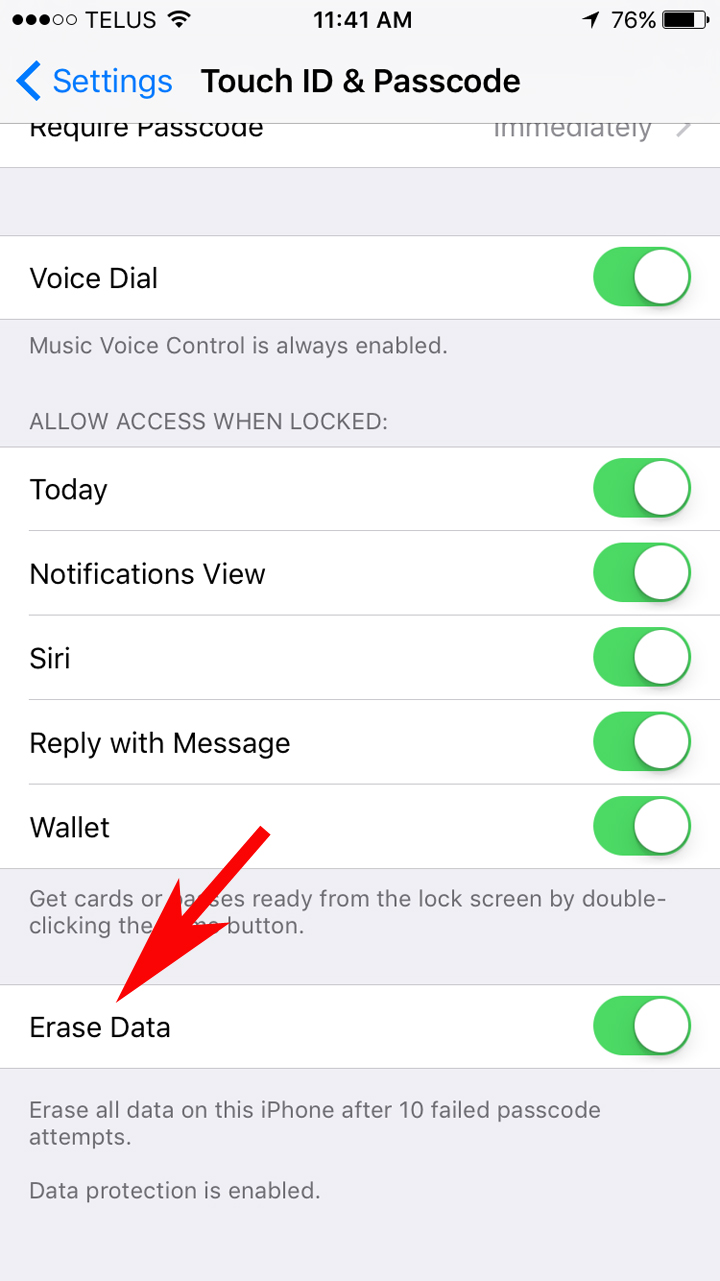

If you have an iPhone handy, go ahead and open the Settings menu.

Scroll down and tap “Touch ID and Passcode” – at the bottom of that page you will see an option that reads “Erase all data on this iPhone after 10 failed passcode attempts.”

This is the main feature standing in the way of the FBI and the information investigators think might be on the iPhone belonging to Syed Farook, one of the San Bernardino, Ca., shooters.

The FBI wants to use what is called a “brute force” attack to hack into the iPhone. This means investigators would use a computer program to enter thousands of numerical combinations to break the code.

READ MORE: How Apple ended up in the government’s encryption crosshairs

Because Farook had enabled the “Erase Data” setting on his phone this approach would never work – it would erase all possible evidence from the phone in only 10 attempts.

But beyond this the FBI would still be at the mercy of Apple’s passcode system – which makes things pretty tough for anyone trying to break into an iPhone.

Apple’s software only allows passcode attempts that are entered by hand – one at a time.

According to Apple’s security guide, each attempt takes approximately 80 milliseconds to process.

“This means it would take more than 5½ years to try all combinations of a six-character alphanumeric passcode with lowercase letters and numbers,” reads Apple’s security guide, using calculations based on over one million six-digit passcode combinations.

The iPhone in question, however, is an iPhone 5C – which means there would only be a four-digit combination.

But that still leaves 10,000 possible combinations to input.

Beyond that, Apple’s operating system also forces timed delays between passcode attempts. After five failed attempts the user is locked out for one minute, six failed attempts locks the phone for 5 minutes, seven to eight attempts disables the phone for 15 minutes and, finally, after nine attempts the phone is locked for an hour.

READ MORE: Apple’s encryption a ‘gift from god’ for criminals, NYC police say

So, even if the FBI didn’t have to worry about erasing the data on the phone, it would still be a long and frustrating road to hacking the device.

Through the court order the FBI has requested that Apple build a special version of its iOS operating system that would disable the “Erase Data” feature, disable the passcode entry delays and allow an external device to be connected to the phone to input the 10,000 possible passcode combinations.

And while the Justice Department is only asking the company to help unlock Farook’s, the company has opposed the order stating there could be no guarantee that the software would limited to this case.

“The FBI may use different words to describe this tool, but make no mistake: building a version of iOS that bypasses security in this way would undeniably create a backdoor. And while the government may argue that its use would be limited to this case, there is no way to guarantee such control,” Tim Cook wrote in an open letter Wednesday.

Newer iPhones make it even trickier for law enforcement

Over the past few years, Apple has put a large focus on the security and privacy features built into the iPhone.

In 2014, during the launch of iOS 8, Apple released a new privacy policy along with a declaration that police can’t get to your password-protected data. With iOS 8, photos, messages and other documents were automatically encrypted when the user set up a passcode.

Starting with the iPhone 5S, the company began using Touch ID fingerprint scanning technology in its devices in the hopes of making passcodes even more secure.

That addition came with something Apple calls the “Secure Enclave” – a separate computer within your iPhone that is entirely independent from the operating system.

The Secure Enclave uses encrypted memory. It features its own unique ID that is not even known to Apple, according to the company’s documents. This mini-computer is responsible for keeping fingerprint data from any Touch ID device safe.

It even checks to make sure that the Touch ID fingerprint hasn’t been tampered with – preventing an attacker from replacing it with a fake sensor. Many iPhone users recently learned this thanks to “Error 53” – a widespread issue that permanently disabled many iPhones that had the Touch ID fingerprint scanner replaced by a non-Apple certified source.

According to security blog Trail of Bits, Apple would likely be able to do what the FBI is asking – but it’s feasible because it’s an older model that does not include this Secure Enclave.

“If the San Bernardino gunmen had used an iPhone with the Secure Enclave, then there is little to nothing that Apple or the FBI could have done to guess the passcode,” Dan Guido of Trail of Bits told MacLeans.

Comments