TORONTO – In just over one month, a tiny dot in the heavens — a dot that has caused a lot of controversy among astronomers over the past nine years — will reveal itself.

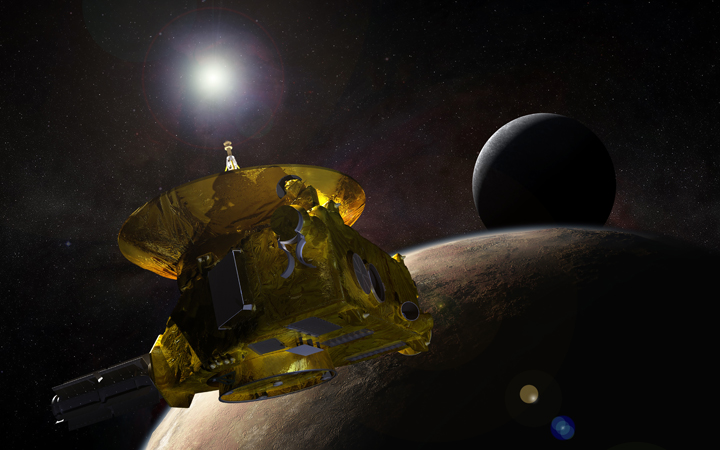

The New Horizons mission is hurtling toward Pluto, once considered the ninth planet in our solar system, but now called a dwarf planet.

READ MORE: ‘We are at Pluto’s doorstep.’: New Horizons mission edges closer to mysterious world

And the spacecraft is travelling at warp speed. Okay, not really, but it’s moving pretty fast. It launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on Jan. 19, 2006 at a velocity of more than 58,000 km/h making it the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth. It continues to speed through the solar system around 52,000 km/h.

The downside is because of that incredible speed, New Horizons won’t stop. Instead, it will make its closest approach on July 14 within 9,600 km of the centre of Pluto’s mass. It will also have slowed down to about 14,000 km/h. But as it nears — and as it passes — it will continue to conduct valuable scientific data.

So why bother spending about $700 million to study a tiny, far-off world?

“Nothing’s happened like this since the Voyager missions,” New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern told a group gathered at the International Space Development Conference in Toronto last week. And it’s the prospect of discovering a whole new class of worlds — as those missions did — that can serve to expand our knowledge of how we got here.

The Voyager missions launched in 1977, visiting Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune. They shed light on the gas giants of the solar system and helped astronomers understand far more than ever before about the formation of our solar system as well as even the hope of finding life beyond Earth.

When it comes to Pluto, Stern told the audience that it may also help us better understand the formation of our own Earth-moon system. It’s believed that Charon, Pluto’s largest moon, was borne out of the same process as what astronomers believe ours was — a massive collision between a celestial object and our planet.

On Pluto, the sun would be a distant, bright dot in the sky. So, seeing as there’s not a lot of sunlight out there, how will the spacecraft get a look at Pluto’s dark side? Science. It will use the sunlight reflected off Charon.

On Wednesday, New Horizons principle investigator Alan Stern, released new images of Pluto, at a distance of about 4.7 billion km from Earth.

“These new images show us that Pluto’s differing faces are each distinct; likely hinting at what may be very complex surface geology or variations in surface composition from place to place,” Stern said. “These images also continue to support the hypothesis that Pluto has a polar cap whose extent varies with longitude; we’ll be able to make a definitive determination of the polar bright region’s iciness when we get compositional spectroscopy of that region in July.”

If you’re looking to keep tabs on where New Horizons is and any news or new photos, there’s an app for that. Pluto Safari, developed by Pedro Braganca of Simulation Corp., allows you to keep track of Pluto’s trip in real-time. It also has a mission timeline and the history of Pluto and the mission. And yes, there’s a poll as to whether or not Pluto should be considered a planet.

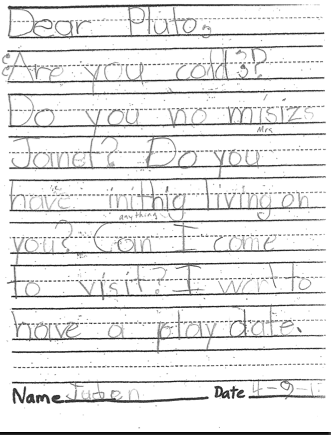

Now, if you have a problem with Pluto not being considered a planet, or perhaps you support the decision, or maybe you or your kids want to give a little word of support to the tiny world, there’s a “Dear Pluto” campaign headed by science educator Janet Ivey, of Janet’s Planet. Children are invited to write a letter or record a short video addressing Pluto. But you can even do it to on Twitter using the hashtag #dearpluto.

As for Stern’s feelings on whether or not Pluto is a planet, he recently had this to say:

So why get excited? Because it will be the first time in almost 40 years where we get to see a distant world close up. A world that has only existed as a tiny spot of light in the sky, a pixellated image at best revealing almost nothing about itself.

And astronomers and scientists around the world are looking forward to another piece in the planetary puzzle.

Comments