TORONTO – Daniel Bausch has come to dread the words “an abundance of caution.”

In the context of the response to the current West African Ebola crisis, Bausch knows if he hears that phrase he’s not going to like the rest of the sentence.

“Public health officials saying ‘We’re doing things out of an abundance of caution’ — that usually means is ‘We’re doing something that has no scientific basis whatsoever, but we’re going to do it anyway,'” says Bausch, an Ebola expert at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, La.

Public health experts and scientists point to a variety of measures that have been taken in the world’s response to the Ebola outbreak where it seems an abundance of caution — some call it politics — have trumped science.

READ MORE: How did 2 U.S. health workers contract Ebola from infected patient?

They include: Entry screening at airports half a world away from the countries in the grip of the outbreak. Closing borders to millions of West Africans from three affected countries because 13,000 people have been infected. Trying to force into mandatory quarantine health-care workers who have risked their lives to volunteer in Ebola treatment centres.

The latter example has received the most public attention, thanks to two nearly back-to-back developments. Dr. Craig Spencer, a New York City resident who had volunteered with Medecins Sans Frontieres, tested positive for Ebola six days after returning to the United States from Guinea. Spencer had been out jogging and had eaten in a restaurant before he realized he was ill. When he spiked a fever, Spencer called MSF and the city’s public health department.

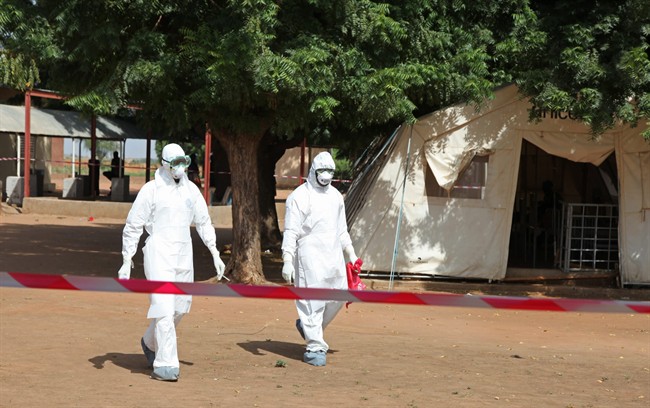

A couple days later nurse Kaci Hickox, an MSF nurse returning from West Africa, found herself quarantined in a tent in a parking lot in New Jersey after that state decided all returning health-care workers would face mandatory quarantine regardless of whether they have symptoms. Hickox had flown into Newark en route to her home in Maine.

She went public with her strenuous objections. When she was released and allowed to travel home, Maine also tried to quarantine her — until a court ruled against the state.

READ MORE: Will a Dallas nurse’s dog suffer the same tragic fate as euthanized Spanish pet?

These events, plus an earlier case where an American nurse coming down with Ebola travelled on a plane, have raised questions about whether returning health-care workers pose a risk to the societies they are rejoining. But as elected officials deliberate on the right course to take, public health leaders warn that treating returning health-care workers like pariahs could hamstring Ebola control efforts by dissuading doctors and nurses from volunteering.

So what does the science say about when Ebola can spread from one person to the next? Bausch and Dr. Pierre Rollin, an Ebola expert at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, are going to help us sort this out.

Q: When are people with Ebola contagious?

The accepted wisdom with this disease is that people who are not displaying symptoms are not infectious.

READ MORE: How does Ebola spread? 5 things you need to know

There is no way to actually test that in people. Because the disease is so deadly, you could never conduct an experiment where you put someone developing Ebola in contact with healthy people to see if transmission occurs.

But Rollin, a veteran of many Ebola outbreaks, suggests years of experience in the field has made scientists pretty comfortable accepting this claim.

Further, he notes that in the first three days after onset of symptoms, you often cannot detect virus in the blood of people suspected of having contracted Ebola.

Health-care workers in the field know that when a person has symptoms that are associated with the early stages of Ebola — things like fatigue, chills, muscle aches and low-grade fever — they shouldn’t accept one negative test as an all-clear. They run a second test within 72 hours of symptom onset.

If virus levels are so low they aren’t detectable, Rollin says the risk of transmission is virtually nil. Bausch agrees.

READ MORE: Why health officials say the Ebola epidemic won’t spread into Canada

“If you have lots of virus, you’re really sick. And if you don’t have much virus, you’re not very sick,” he says.

Q: Can you be sure of that?

Rollin acknowledges that with diseases, you can never say never. But he points to another reason to believe people who don’t have symptoms — or are just starting to experience symptoms — pose little if any risk to anyone else.

You don’t contract Ebola by being in the vicinity of someone who has the disease, or breathing the same air as they do. Ebola spreads when healthy people come in contact with the bodily fluids of infected people. Those fluids — primarily blood, diarrhea and vomit — are teeming with Ebola viruses.

But Ebola patients don’t generally start to suffer from vomiting, diarrhea or bleeding until three, four or five days into their illness, Rollin says. By then they will have already noticed they are feeling unwell and will likely have had a fever. Health-care workers like Spencer who report those early signs should be in isolation by the time they reach the stage of the disease where they are spewing out viruses.

READ MORE: Why this U.S. nurse fought to be released from Ebola quarantine

There are some diseases where people are infectious before they even know they are sick — chickenpox, for one. But that is not the case with Ebola.

“It’s an awful virus. But usually you see him coming,” Rollin says.

He notes that in decades of outbreaks, it became clear that if people coming down with Ebola were isolated within the first couple of days of their disease course, they didn’t infect others.

“The epidemiology supports it, over and over. Every time we … remove them from the community in the first 48 hours, you really cut the chain of transmission,” Rollin says.

Q: What about sweat? Traces of Ebola virus have been found in sweat. Could someone contract the disease from touching a surface touched by a person who is coming down with Ebola and is feverish?

Bausch says a couple of studies have found Ebola virus in sweat, but in both cases the people were in the late stages of their illness. That’s when you would find a lot of virus in a person’s system.

And one of the few post-mortems of a person who died of Ebola found virus in a sweat gland. But that’s a different scenario, he says, than what you would expect to see in a person coming down with Ebola who has just broken a fever.

Rollin agrees. He think sweat generated at the end of the illness and sweat at the beginning — when the amount of virus in a person’s system is still low — are not the same, riskwise.

Bausch says the ability to find traces of virus in sweat or on the skin is relatively new, and is, in some ways, a mixed blessing. Just because you find viral traces doesn’t mean you have actual viable viruses that can infect a healthy person, he says.

He notes that an important study done during the 1995 Kikwit outbreak — in the Democratic Republic of Congo — showed that most of the person-to-person transmission occurred when people were exposed to patients who were late in their illness, or to their corpses after death.

That study contains important information for assessing the transmission risk in cases where people are incubating the disease but aren’t yet sick.

It showed that of 78 people who lived with someone who developed Ebola, and who shared meals with them, none became ill. Of that group, 26 reported having direct physical contact with the person who became sick, 15 shared a bedroom and six shared a bed with the person who became ill. None of them contracted the disease.

Even in the early stages of the illness, the authors reported, 62 of the 78 slept in the same house with the sick person and 42 shared meals with the sick person. Again, no transmission.

“There are these years of observational experience that count for something,” Bausch says.

Comments