TORONTO – In its monthly update, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has reduced its prediction of an El Niño event occurring this year.

The onset of the El Niño is now forecast to occur somewhere between July and September and continuing into 2015, and instead of it being strong, as observations had indicated earlier in the year, it is now anticipated to be a weak event.

An El Niño – Spanish for “little boy” – occurs when warm water near Indonesia moves to the eastern Pacific. This creates varying effects for countries around the world.

READ MORE: El Nino – What it is and why it matters

In 1997-1998, the world saw the strongest El Niño event it had seen in 50 years. Countries in the eastern Pacific battled floods, landslides, drought and super typhoons. In Canada, it was the second warmest winter in our history. But it also brought the “Ice Storm of the Century,” which occurred in Quebec and Ontario.

Gallery: The effects of an El Niño event

That El Niño killed an estimated 23,000 people and caused more than $33 billion in damage.

Forecasters anticipate the El Nino to emerge during August to October and peak in late fall or early winter.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology has also reduced its forecast for an El Niño to just 50 per cent, down from an earlier forecast of 70 per cent.

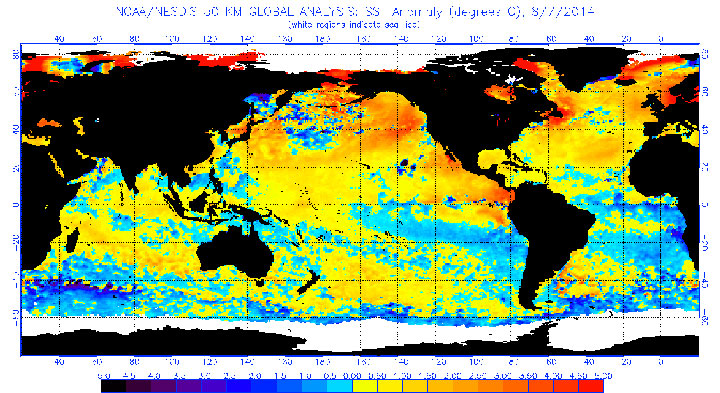

Though above-average surface sea temperatures (SST) continued in the far east along the equatorial Pacific, east and east-central SSTs of the same area remained near average.

“In May we thought that El Niño was really starting to get ready to develop, and in fact, it hasn’t,” said Gerry Bell, a meteorologist and El Nino expert with NOAA. “In addition the ocean temperatures in the central Pacific have cooled a bit, and that’s giving us more uncertainty as to when El Niño will form and how strong it’ll be.”

READ MORE: Hurricane season forecasts tied to El Nino

What’s making things difficult to forecast is something called oceanic Kelvin waves, which travel from the west to the east. There are two types: downwelling and upwelling. If these waves are downwelling, the surface ocean temperature warms. If it is upwelling, it draws up cold water, cooling the ocean surface.

In the spring, there was a downwelling which lead forecasters to believe that an El Niño would begin to form.

“Except that didn’t happen,” Bell said. “It’s because of these strong Kelvin waves producing so much variability that it’s just not clear if this Kelvin wave activity is going to weaken and we get into an El Niño or not. There’s less confidence that we will because this Kelvin activity is so strong.”

“This is not typical to have this much Kelvin wave activity. It’s very atypical.”

For Canada, and the drought-stricken U.S. south, an El Niño could be a good thing: it would bring rain to the west coast and a warmer winter to central Canada, something that many would welcome after last year’s harsh winter.

But, Bell said, “I think we just need to wait and see how the ocean and atmosphere are evolving.”

Comments