By

Alex Cooke

Global News

Published August 17, 2023

12 min read

This is the fourth instalment of New Roots, a series from Global News that looks at how evolving migration patterns and affordability challenges have changed life in communities across Canada since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Helen Babineau wants to return to her home province of Nova Scotia, but that just isn’t in the cards right now.

Originally from the Cape Breton community of Chéticamp, Babineau moved to the Northwest Territories with her then-husband in 2019 for a work opportunity.

When the marriage ended, she returned to Nova Scotia in June 2021 – but not for long. The following year, she found herself moving back up north as life had become unaffordable at home.

“I can support myself here, whereas in Nova Scotia, I couldn’t,” Babineau, 53, said in a phone interview from her home in Yellowknife last week.

“I would like to move back to Halifax, where my children are, but I can’t afford to.”

Babineau is just one of many Nova Scotians who feel like they are being priced out of their home province due to the rising cost of housing, groceries, and other essentials.

A big part of the issue, she said, is the province’s low wages. Babineau, who works in the daycare industry, said while the cost of living in the Northwest Territories is similar to Nova Scotia, she makes much more money up north.

In Yellowknife, she earns about $42 an hour. In Nova Scotia, she made about $18.

Babineau is sad to have been priced out of the province she’s lived in her whole life, and hopes she can return someday.

“It’s gut-wrenching. I’m so far away from home,” she lamented.

“I miss my family extremely, but I also don’t want to be a financial burden on my children when I get older, so I have to work and make some kind of a pension for myself so that maybe I’ll be able to live in a nursing home in Nova Scotia.”

Historically, Nova Scotia has been seen as a more affordable place to live when compared with larger provinces like Ontario and B.C. – but due to low wages, life still isn’t affordable for many people.

According to Statistics Canada, Nova Scotians had the second-lowest median household income of all provinces in 2021, second only to neighbouring New Brunswick.

The minimum wage in Nova Scotia is $14.50 per hour and is scheduled to rise to $15 in October. The current minimum wage is the third-lowest in the country, tied with P.E.I. and Newfoundland and Labrador. Only Saskatchewan ($13) and Manitoba ($14.15) have a lower minimum wage than those provinces.

Even with the upcoming wage increase in October, it still falls far short of what’s considered a living wage. According to a September 2022 report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the living wage in the Halifax area was $23.50 last year.

The living wage is calculated based on how much a family of four, with two parents working 35 hours a week, would have to earn to cover all necessities and have a decent quality of life.

Carrie Boudreau, a single mother of two, knows all too well how hard it can be to make ends meet.

The Dartmouth woman currently earns about $15 an hour working in a vision clinic, which she said “no one can live off of.”

“Oh, I struggle,” she said with a laugh. “There’s times where I can’t pay bills.”

With the cost of living rising so rapidly, Boudreau said there should be an equal increase in pay.

“The employers in this province need to realize that people can’t live off of what they make. We need to have a good pay raise in order to survive,’ she said.

“We have to be able to put food on the table, we need to be able to pay our rent, we need to be able to pay our bills and be able to live comfortably. And I just find employers don’t see it that way.”

Boudreau, who is originally from Ontario but moved to Nova Scotia nearly 20 years ago, said she would someday like to move back to her hometown, but right now she can’t afford to.

“I’m kind of stuck in a hard spot,” she said.

Nova Scotia’s population has grown drastically since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, which helped drive up housing demand and prices. At the height of the pandemic, the province became an attractive place for those coming from more populous provinces, looking to escape high caseloads and housing prices.

There was a time just a few years ago when the province – which now has a population of just over a million – had been experiencing an exodus of people moving to places with more opportunity.

That time now appears to be far behind, as more and more people are choosing to call Nova Scotia home.

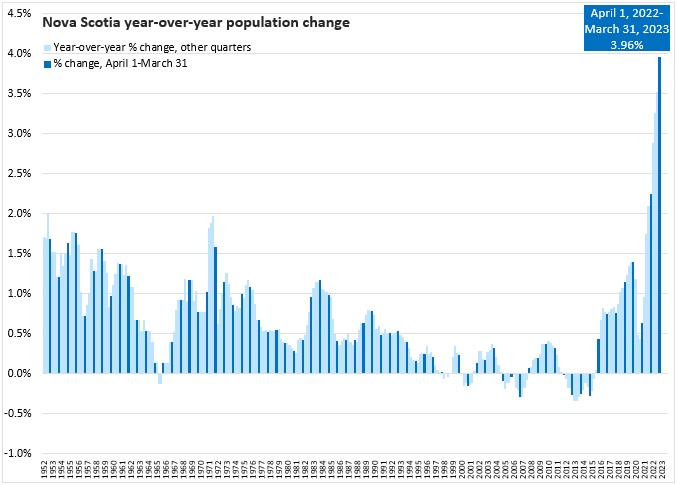

In a one-year period ending April 1, 2023, Nova Scotia added 39,872 more people to its population — an increase of nearly four per cent from the previous year, according to provincial data.

“This was the fastest year-over-year growth for Nova Scotia’s population for any 12-month period of the quarterly data that started in 1951,” the province said in its most recent quarterly population estimate.

“Since ending a period of population decline on April 1, 2015 Nova Scotia’s population has increased by 110,961.”

Between January and April of this year, the population increased by 9,450, thanks in large part to immigration (which added 3,936 people), non-permanent residents (3,827) and interprovincial migration (2,690.)

During that time period, the “natural population” declined by 876 people, as deaths continue to outweigh births, and 127 people moved away.

In terms of interprovincial migration, Nova Scotia is an especially popular destination for people from Ontario. During a one-year period ending June 30, 2022, 15,862 people moved from Ontario to Nova Scotia, according to data from Statistics Canada.

Emilie Jean-Jean is one of them, having moved to the Bedford area of Halifax in May 2022.

Originally from France, she moved to Toronto in 2011, where she lived for a few years before moving to London, Ont., in 2015.

The decision to move to Nova Scotia came after a lot of consideration and planning. She didn’t necessarily make the move due to finances, but to increase the quality of life for her and her seven-year-old daughter.

She wanted to be close to the ocean and have a more relaxed pace of life compared to that in Ontario.

“I made the decision based on my priorities,” she said.

“It’s not all about the money, it’s all about the comfort and what you have access to.”

But, as with many things in life, finances were a consideration.

Having sat down and compared budgets prior to the move, Jean-Jean thought Nova Scotia would be more affordable. But after she arrived, there were extra utility costs and a hit to her paycheck that made life more difficult.

“I don’t regret it,” she said of the move to Nova Scotia. “It’s just that I’m a planner and my impression of what it was going to be like was very different.

“I didn’t expect to struggle.”

She said her electricity bill is much higher than it was in Ontario.

“I blow up my budget just on heating the house,” she said.

As well, Jean-Jean, a teacher, said credentials she earned in the U.K. and Ontario aren’t recognized in Nova Scotia, so her pay in Ontario was “pretty much double for the same qualifications.”

“Being paid less and having more expenses is definitely not something I had planned,” she said.

Jean-Jean taught high school in Ontario and is currently teaching junior high in Nova Scotia. She is now working on an online master’s so she can work her way back up the pay scale, but she is frustrated with the system.

“I have sacrificed two years of night classes where I can’t really spend time with my daughter just so I can have hope that the pay will get better,” said Jean-Jean.

Despite moving to Nova Scotia with “Ontario money” – having sold off her house in London at the height of the real estate boom – the unforeseen costs and wage decrease have already eaten through much of her savings.

“It’s almost all gone because of all the things I couldn’t plan,” she said. “It’s something I couldn’t have figured out without actually making the move.”

Jean-Jean was clear that she loves Nova Scotia and doesn’t regret the move, but she wishes life was more affordable.

“I don’t want to sound like I’m not happy about the move, and I’m not criticizing the province at all,” she said. “Things are working out slowly but surely.”

It’s a similar story for Christina Churchill, who moved to Nova Scotia from Alberta two years ago in April. While she loves living in Nova Scotia, she said there were a ton of “hidden costs,” like expensive power bills due to the Nova Scotia Power monopoly, and high land transfer and property taxes.

“It’s almost like the province is really nickeling and diming us,” said Churchill. “Every opportunity that they can get money from the residents of this province, they’re right there with their hand out.”

She took note of the province’s struggling health-care system – in which 152,001 people are on the waitlist for a family doctor, representing more than 15 per cent of the province’s total population.

She questioned if Nova Scotians are getting their tax money’s worth in health-care, education and infrastructure.

“All these people are coming to this province, and they’re paying these land transfer taxes, and they’re paying higher property taxes … You think about the large sum of money that’s coming into the province, where is that going and what are they doing with it?”

The influx of people coming to Nova Scotia caused a real estate frenzy, driving up prices to levels never seen before in a province once known for its cheap housing.

At the height of the pandemic, houses were flying off the market, with bidding wars and purchasing homes sight-unseen a common part of house-hunting. Rock-bottom vacancy rates have also driven up the price of renting, with Halifax seeing the largest year-over-year average rent increase out of all cities in Canada last year.

The housing market has now cooled somewhat, but prices remain well above pre-pandemic levels and new homeowners are still feeling the pinch from sky-high interest rates. According to the Nova Scotia Association of Realtors, the average price of homes sold in the province last month was $435,293, up by 14.3 per cent from July 2022.

Twenty-five-year-old Kyle Greenlaw, who recently purchased his first home with his girlfriend, acknowledges he was lucky to be able to do so. The young couple have good careers – he, a pilot; she, a nurse – and were able to move back home for a while to pay off debt and save money for a down payment.

Still, the split-entry duplex is “definitely stretching our budget,” said Greenlaw, who is from Lower Sackville, N.S. They purchased it in October for about $345,500 – after the house had previously sold for $185,000 back in 2018.

“Homes on this street used to sell for like, $100,000, $150,000, $200,000, like, five years ago,” said Greenlaw. “And we’re paying what is essentially almost a hundred per cent markup on the house.”

Soaring interest rates are having an impact on their bottom line as well. The rate was about 3.7 per cent when they bought the home, but it has since ballooned to more than 6 per cent.

“So we’ve pretty much doubled our interest rate almost, and I think we’re paying an additional $500 to $600 just in interest payments alone,” he said.

Greenlaw said the couple felt they were “forced” to buy the home at the time, given the precarity of the housing market.

“People saying, ‘Buy now, buy now, buy now, because if you don’t, you’re not going to be able to,’” he said. “At least if we’re in the house we can kind of sit and ride the wave until the interest rates can come back down.”

Greenlaw said it’s disappointing that the dream of homeownership is getting increasingly out of reach for the younger generations. He said he’s the only person out of his friend group that has been able to buy a house.

“I would love to be able to see all my friends own homes and be able to comfortably afford them,” he said.

It’s clear that affordability challenges are being felt by all generations.

Dale Nadeau, originally from Saint John, N.B., moved out west with her husband for work back in 1981, where they stayed for 40 years.

But during that time, the couple were homesick for the Maritimes and yearned to move back someday.

“At some point, in the back of our minds, our dream would be to come back home,” said Nadeau, 70.

That dream came to fruition in 2021, when they bought a home just outside the Nova Scotia community of Mahone Bay. But cost of living increases have strained the couple.

“It’s very expensive to live here,” Nadeau said, noting that power, taxes, and groceries are their biggest challenges. “I used to love grocery shopping, and now I have anxiety attacks before I go because it’s so expensive.

“We are struggling more financially than we thought we would.”

While Nadeau and her husband are technically retired, both have picked up casual work to help get by.

Her husband, 74, works in a liquor store. Nadeau worked for a while as a substitute TA with the school district, but she stopped after a nasty bout of COVID-19 in November.

The pay was also around $15 an hour – “not worth my gas money,” she said.

Their situation makes Nadeau concerned about the future.

“We’re going to have to really seriously think in a couple years – what do we do now if this house is too much for us?” she said. “I don’t think we can afford to keep this house and not work.”

While Nadeau said it’s “a bit disappointing” that they have to work during their retirement, she said many other people are in a similar position.

But all in all, she doesn’t regret the move back to the Maritimes.

“We are here because of the people, the beaches – oh my God, just to be on the beach is the most wonderful thing. I’ve missed it so much,” she said.

“I appreciate the Maritimes so much, and I’m certainly not angry that we’re here, but … if all these prices are going up and there’s more and more people, people need to be able to earn a fair wage and not pay as much in taxes.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.