The passing last week of a former B.C. labour leader was a reminder of how much both the labour movement and the so-called “political left” have changed in this province.

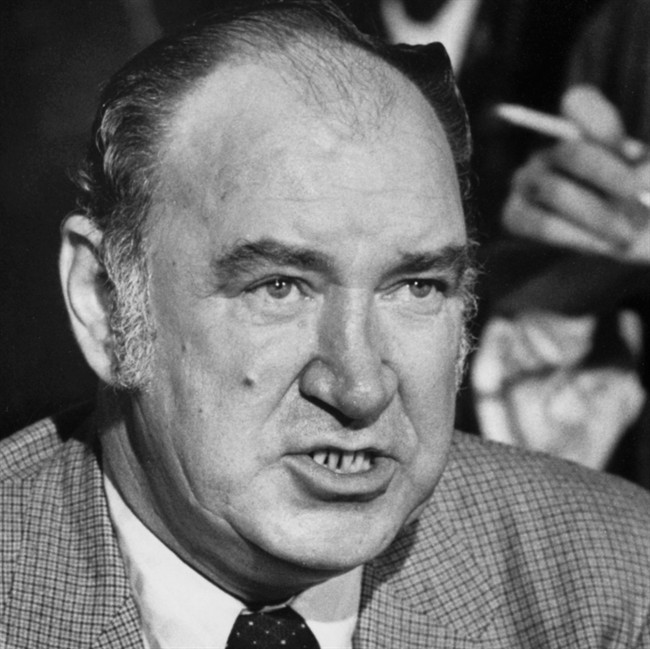

Jack Munro was a colourful, powerful leader of the most powerful union in this province. He led the IWA (the primary forestry workers union) for decades and was one of the most influential labour or political figures in the B.C. Governments of all stripes were wary of taking him on. A prolonged strike in the forest industry could cripple the provincial economy, and Munro was mindful of his power.

His influence was wide within the B.C. Federation of Labour, and he was often seen as the face of unionized labour.

In those days (the 1970s to the mid-1990s) organized labour wielded a major sword. At first, that sword was held by private sector unions but over time public sector unions wrenched it away to become the main power bloc in the labour movement.

That is one of the crucial differences that have evolved in the House of Labour. The days of private sector union domination are over, and therefore so are the days of a private sector union leader like Munro having huge influence.

Get daily National news

For years, private sector strikes, some of them quite lengthy, were regular events in all kinds of industries.

Now, public sector strikes are the main characteristic of any labour strife in this province.

Another change from Munro’s hey day is the collapse of the forest industry. The IWA is gone, and so are many mills that provided many communities with thriving local economies.

The forest industry, and its unionized workforce, no longer has the political clout it had when Munro was one of industry’s main players.

And then there is the political left in B.C. For years, during Munro’s time, the left was dominated by private sector union leaders but gradually, over time, their influence was matched, and then exceeded by social activists, environmental activists, and public sector union leaders.

During the 1983 Solidarity crisis, it was Munro who essentially ended an escalating protest that was headed to a province wide general strike. Munro had no interest in taking private sector union workers off their jobs to appease social activists itching to topple an elected government, and he made that very clear.

As a result, he was vilified by many of those activists, who viewed his actions as a form of betrayal.

A decade or so later, a left-wing government was in power, but the environmental movement caused the NDP administration to back down on its forest policies, constituting a landmark win for the greens. During Gordon Campbell’s term in power, most of his opposition came from public sector unions, many of whose contracts he was trying to tear up or change. The private sector remained relatively quiet, and the environmental movement seemed to be biding its time.

And, of course, there was the NDP’s sudden reversal on the Kinder Morgan pipeline project in the last election campaign.

It was done to appease the environmental movement, but the move has revealed a breach in the party’s relationship with socalled blue collar workers (the ones championed for so long by the likes of Munro).

The NDP, the party of the left, is now almost shutout of the IWA’s old turf, as mills have closed and workers have disappeared. Its support is more concentrated in urban centres. One has to wonder what Munro would make of this ongoing shift in the party and movement he was once so active in. I can’t see him liking where things seem to be headed.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.