By

Stewart Bell

Global News

Published June 22, 2023

8 min read

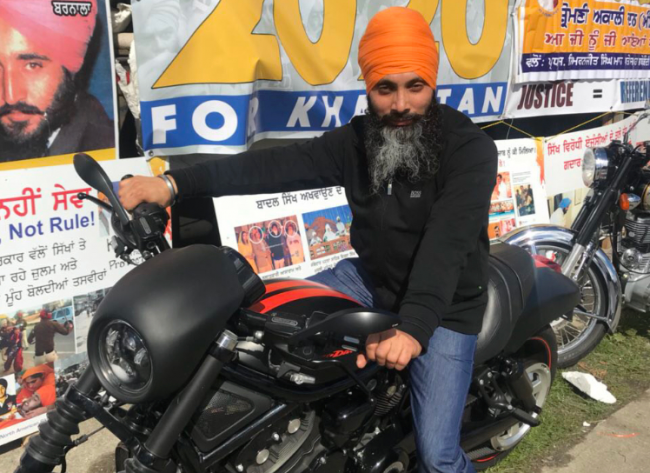

Hardeep Singh Nijjar was a plumber who served as president of a Sikh temple in Surrey, B.C. He was also wanted in India, where he was accused of being a leader of a militant separatist group.

That contradiction did not die with him when he was gunned down in a temple parking lot on Sunday night. Since then, he has been both mourned as a community leader, and cast as a terrorist.

Speaking to Global News long before his killing, the 45-year-old insisted India was falsely smearing him in retaliation for his activism in support of Sikhs.

Whether or not that was true, India wanted him arrested. The RCMP did so once, but he was not charged, although he was put on Canada’s no-fly list.

The investigation into his murder is taking place amid concerns India may have grown tired of waiting for his arrest and ordered his killing.

His friend Gurpatwant Singh Pannun said Nijjar told him Saturday that gang members had warned him Indian intelligence agents had put a bounty on his head.

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service also told Nijjar they had information that he was “under threat from professional assassins,” Pannun said.

“We’re open to any potential motive at this time,” the RCMP homicide unit investigating Nijjar’s killing said on Wednesday.

But investigators are grappling with a question they so far cannot answer: if not an extreme act of foreign interference by India, then what else could it be?

Nijjar arrived at Toronto’s Pearson airport on Feb. 10, 1997, using a fraudulent passport that identified him as “Ravi Sharma,” according to his immigration records, obtained by Global News.

His refugee claim said he feared persecution in India because he belonged to “a particular social group, namely, individuals associated with Sikh militants.”

In the account he gave immigration officials, he said his troubles began in 1990, during a police crackdown on the insurgency in Punjab.

Amid attacks by militant groups seeking independence for the Sikh-majority state, police arrested Nijjar’s brother Jatinder, he wrote in a sworn affidavit.

Following the arrest, Nijjar said his father sought help from a human rights group. As a result, his father was himself arrested and tortured, he said.

In 1995, police came for Nijjar as well, he wrote. They took him to the police station in the city of Phillaur, he said.

To coax him to give up the whereabouts of his father and brother, police hanged him with his hands behind his back and electrocuted his “private parts,” he said.

“When they would do bad things, and beat me, they would ask about my brother Jatinder Singh and father accusing me that I shelter militants,” he said.

Threatened with death, he said he arranged a 50,000 rupee ($800) bribe to secure his release. He cut off his hair to change his appearance and hid out at a relative’s house.

Police raided the home in Uttar Pradesh in 1996, but Nijjar said he was away working as a “truck helper,” and his uncle was arrested instead.

“I know that my life would be in grave danger if I had to go back to my country, India,” he wrote in his affidavit, dated June 9, 1998.

But Canadian refugee officials didn’t believe him. They said a letter he submitted to support his narrative had been fabricated.

The letter was supposedly written by an Indian physician who said he had treated Nijjar after police electrocuted his “intesticals.”

The misspelling of a body part, together with an account that refugee officials found implausible, led them to dismiss him as unreliable and untrustworthy.

“The panel does not believe that the claimant was arrested by the police and that he was tortured by the police,” according to the ruling.

Eleven days after his refugee claim was rejected, Nijjar married a B.C. woman who sponsored him to immigrate as her spouse.

“I do not want to live apart from my wife even a single day,” he wrote, as he embarked on his second attempt at a life in Canada.

On his application form, he was asked whether he was associated with a group that used or advocated “armed struggle or violence to reach political, religious or social objectives.”

He wrote: “No.”

To show the authenticity of the union, he submitted a wedding invitation, wedding photos, and a picture of the couple cuddling in a chair.

But immigration officials considered it a marriage of convenience and rejected Nijjar’s application.

They also noted his wife, who worked for a Surrey produce company, had arrived in Canada in 1997, sponsored by a different husband.

Nijjar appealed to the courts and lost in 2001, but he later identified himself as a Canadian citizen.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada declined to comment, citing privacy legislation.

In Surrey, Nijjar ran a small plumbing business and fathered two children, while also agitating for Sikh rights.

He travelled to Geneva in 2013 to ask the U.N. Human Rights Council to recognize anti-Sikh violence as a genocide.

At U.N. headquarters in New York in June 2014, he lobbied for a referendum for the independence of India’s Punjab state, he wrote in a letter.

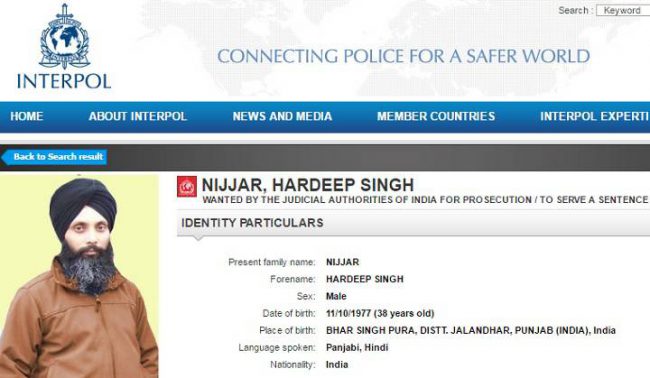

Five months later, on Nov. 14, 2014, India issued a warrant for his arrest through Interpol’s National Central Bureau in New Delhi.

The document described him as a “mastermind/active member” of the Khalistan Tiger Force militant group.

A summary of the case said Nijjar’s name had surfaced following the 2007 bombing of the Shingar Cinema in Punjab.

Suspects arrested for the blast confessed they were “acting under the instruction of Hardeep Singh Nijjar,” according to the summary.

Pannun, a Canadian lawyer and activist, said Nijjar was accused of conspiracy in the cinema bombing but all the other suspects were acquitted.

“So who did he conspire with? Nobody,” he said.

A second Interpol notice in 2016 made fresh accusations against Nijjar, calling him the “mastermind and key conspirator of many terrorist acts in India.”

Like before, the summary said suspects had pointed to Nijjar as having passed on the orders of the Tiger Force leadership.

It said he was wanted for committing acts of terrorism, as well as recruiting and fundraising, and faced a possible life sentence.

Confronted with the allegations, Nijjar denied them in a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, calling them “baseless and fabricated.”

He portrayed them as a campaign to discredit him in response to his activism, and said his father and brother had been warned that, “If Nijjar does not stop his anti-India campaign, we will implicate him in criminal cases.”

Despite the allegations of terrorism, Nijjar took over the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara in 2018, becoming president of the federally registered charity.

According to Surrey provincial court records, Nijjar was charged with assault in March 2019, but the case was stayed that December.

A later dispute over a commercial printing press may have put Nijjar at odds with Ripudaman Singh Malik, who was acquitted of involvement in the deadly 1985 Air India bombings.

The machine was purchased by Malik and a partner, who intended to use it to print Sikh religious scripture, according to court documents.

Malik handed the press over to Nijjar in November 2020 “for safekeeping,” according to B.C. Supreme Court records.

But Nijjar refused to return it, a civil suit alleged. Malik was murdered in July 2022. A lawsuit launched in February 2023 sought the return of the equipment.

Recently, Nijjar was working on a planned referendum on independence for India’s Punjab that was scheduled for Sept. 18, said Pannun, who is with the group Sikhs For Justice.

But he was worried about his safety.

Pannun said Nijjar phoned him and said gang members had warned him that Indian intelligence agents had placed a bounty on both their heads.

Nijjar also disclosed he had been approached by CSIS officers who were concerned, Pannun said, adding he was to meet them on June 20.

“Additionally, it was only a few weeks earlier that India’s NIA (National Investigation Agency) had announced a reward of 1 million (CDN$16,000) for Nijjar,” Pannun said.

On Sunday, Nijjar left the temple and got into a gray Ram 1500 pickup. He was leaving the parking lot at just before 8:30 p.m. when two men shot him through the driver’s window.

Police described them as heavy-set males with covered faces. They fled south to a getaway car, police said on Wednesday.

The World Sikh Organization of Canada has asked for an investigation into whether India had a role in the killing.

“Nijjar openly and repeatedly stated that he would be targeted by Indian intelligence and this was made known to CSIS and law enforcement,” the WSO said.

India has long complained that Canada is a base for extremists active in separatist violence. In 2018, Canada and India signed a co-operation framework pledging to work together on the issue.

Pannun said he believed that after India’s campaign to tarnish Nijjar’s reputation failed, he was targeted for killing.

He said he had no doubt India was behind it.

“From the time he started actively campaigning with us, he got noticed and they started pursuing him,” he said.

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments