Across the country, there has been a growing dispute within the Métis Nation over who is, and isn’t, Métis.

“The Red River Métis and the historic Métis Nation need to stand up for what we actually are,” said Will Goodon of the Manitoba Métis Federation. “We’re not just a mixture, we are an actual, distinct Indigenous nation.”

Infighting amongst Métis got so bad that the Manitoba Métis Federation left the Métis National Council in 2021 saying the national body wasn’t doing enough to sanction the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) — the representative body of Métis people in Ontario — over identity and claims to territory.

The Métis debate has reached a boiling point in Ontario as First Nations Chiefs have begun to weigh in.

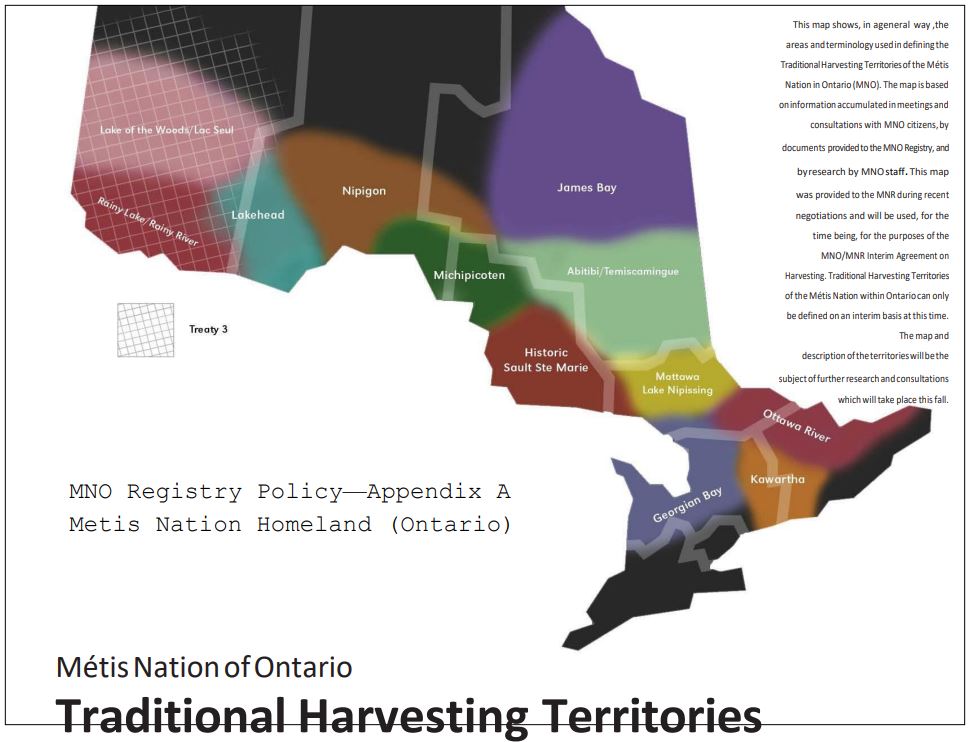

At issue is the location of historic Métis communities and the power that comes with signing a self-government agreement that may impact First Nations.

The MNO signed a self-government agreement with the federal government in 2019 and an implementation agreement in February 2023.

A self-government agreement typically sets up new funding agreements and transfers jurisdiction over decisions like governance, social and economic development, education, health, and lands, as well as authority over the delivery of programs and services.

Prior to signing their self-government agreement, the MNO conducted research to identify historic Métis communities in Ontario. In 2017 six were co-announced with the province, most of which overlay Treaty territory.

First Nations are concerned that the MNO will exercise its jurisdiction on their land without consultation. As the Métis Nation of Alberta and Métis Nation of Saskatchewan have also signed self-government agreements with the federal government this issue could have far-reaching impacts.

Numerous First Nations organizations across Northwestern Ontario have rejected the MNO’s self-government agreement and claims of historic Métis communities.

The Wabun Tribal Council — located near Timmins — has filed an application for judicial review in federal court. The Robinson Huron Waawiindamaagewin Chiefs disavow the presence of historic Métis communities and commissioned a report to that effect.

Get daily National news

The Chiefs of Ontario joined in saying; “MNO’s recognition of these aforementioned communities relies on changing the identities of First Nations individuals into Métis, simply because they are mixed-race, and not because they identified with an existing Métis community. Mixed-race does not mean that someone is Métis.”

Grand Council Treaty #3 has also rejected the MNO’s claims and self-government agreement. Even some Métis organizations outside the province agree.

“With the First Nations in Ontario having this really ‘come to Jesus’ moment … I think it underlines what we’ve been saying for so many years that the Ontario Métis — outside of the little part (around Kenora, Ont.) — is very much not us,” says Goodon. “They are not part of the historic Métis nation.”

Some in Temagami and Teme-Augama Anishnabai communities, near Surbury, Ont. even allege MNO is using their ancestor’s as their own to prove presence in the area.

“They used a picture of mine and (Temagami First Nation Chief) Shelly’s great-great-grandparents,” said Teme-Augama Anishnabai Second Chief John Turner.

“It seems to us a case of identity theft of our ancestors, our family portraits are being used to convey a sense there’s some legitimacy behind their claims.”

“What they are doing essentially is just claiming these identities through censuses, erasing stories, erasing our oral history,” adds Temagami Chief Shelly Moore-Frappier.

“There are no Métis in our territory, in our homeland … If you’re an Indigenous person in N’dakimenan (their word for the region) … you are Teme-Augama Anishnabai. You are not Métis.”

First Nations are also upset that they weren’t consulted by the provincial and federal governments before the signing of MNO’s self-government agreement.

According to the Temagami and Teme-Augama Anishnabai, a member of the MNO even built a cabin on their territory.

“The notion of the research being flawed to me became clear because we were telling the province, like, what? What’s the nature of this claim or this asserted Métis (homeland)?” said Turner.

“They claim that the gentleman was supported by the leadership at the MNO and they sent us a link (to the MNO website) to just where his claim was justified.”

MNO president Margaret Froh says it shouldn’t shock anyone that First Nations and Métis share ancestors.

“It’s troubling and disappointing but at the same time I think we still have a lot of education to do within this country including with our First Nations kin,” said Froh. Adding that the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed 20 years ago with the Powley hunting rights case that Métis do exist in Ontario.

She believes there is likely some confusion around what the self-government agreement and federal recognition and implementation actually entail. “This is not about lands. It’s all about recognizing our right as Métis to govern ourselves.“

Like many Métis organizations to the west, Froh defines Métis as a distinct people who are descendants of historic Métis communities that were here before Canada. “That’s why we as Métis people are recognized within Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act,” she said.

“The MNO has always positioned ourselves as the eastern border,” Froh adds. “We do not recognize Métis in Quebec, we do not recognize Métis in Eastern Canada … there are a lot of groups (there) that are popping up that oftentimes are there, I think, to undermine First Nation rights, which we find appalling.”

Goodon, a self-described historic Métis Nation protector, says the situation in Ontario needs to be handled swiftly before bad blood spreads.

“When we look at this idea of the ancestors that MNO is recreating … they’re looking at folks who are trying to assert that they’re Métis today, then they go back in time, find this ancestor, rebrand this person as Métis because of some document that they have found, and then they are able to again assert that the present-day person is Métis,” he said.

Adding, “(outside) academics have found no connection to the historic Métis nation (in certain parts of Ontario) and the connections that they have are actually connected to the First Nation. So where does that leave these so-called new communities that MNO has created? In my opinion, it leaves them nowhere.”

Comments