A British Columbia Supreme Court judge ruling on a First Nations land title lawsuit says it did not prove it had rights to its entire claim area, although he suggested it may be time for the provincial government to rethink its current test for such titles.

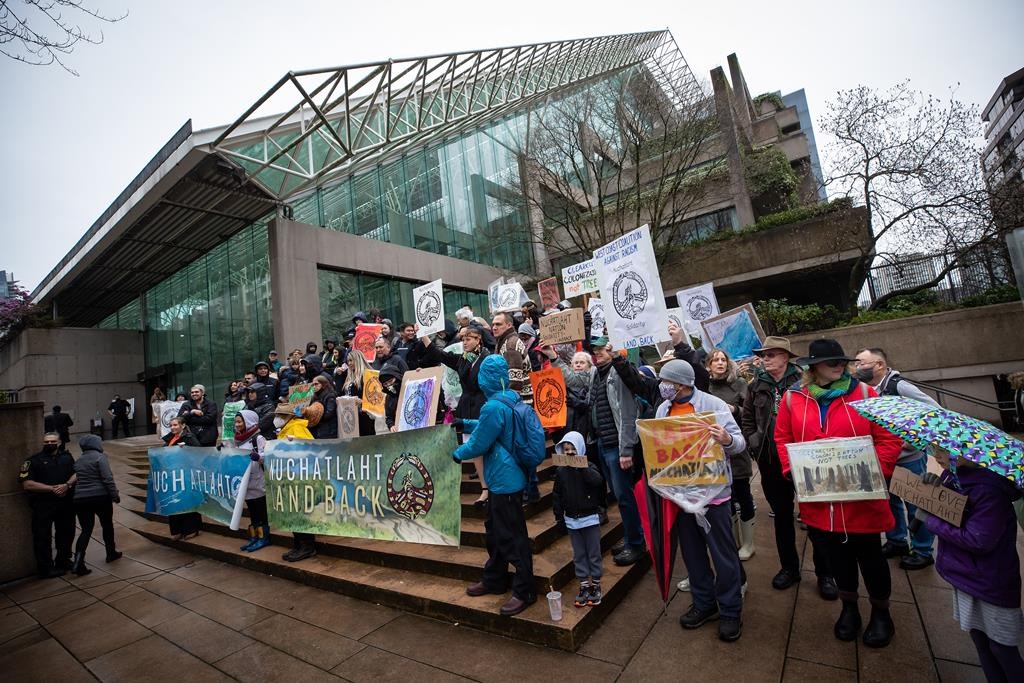

The Nuchatlaht First Nation, a community on Vancouver Island’s northwest coast, wanted title over an area of Crown land that included a portion of Nootka Island and much of the surrounding coastline.

Justice Elliott Myers said in his decision issued Thursday that there “may be areas” the nation can establish in its claim, but if it wants to do that another hearing would be required.

“I stress that I am not prejudging any of the issues or whether a pleading amendment would be necessary,” he said in the decision. “I am merely leaving it open to the plaintiff to come back before me to canvass these issues should it wish to do so.”

He’s given the nation 14 days to decide if it wishes to proceed on the further claims.

The court heard the Nuchatlaht moved to a village on Nootka Island in the 1780s and they say they occupied the area in 1846, when the Crown resolved boundary disputes with the United States and claimed sovereignty over what is now British Columbia.

Get breaking National news

However, the province denies the Nuchatlaht occupied all of the territory it was claiming.

“Nuchatlaht are considering their options at this time,” Owen Stewart, a lawyer for the First Nation, said in an email.

In the lawsuit filed in 2017, the nation argued that the B.C. and federal governments denied Nuchatlaht rights by authorizing logging and “effectively dispossessing” the nation of territory.

The B.C. government denied the Nuchatlaht hold Aboriginal title over the 230-square-kilometre area, and said it has met its obligations under agreements with the nation related to forest resources.

Myers said in his decision that the case demonstrates “the peculiar difficulties of a coastal Aboriginal group meeting the current test for Aboriginal title, given the marine orientation of the culture.”

For example, he said it is difficult to prove the nation had used the land because they primarily travelled by canoe so there were no established trails between coastal locations.

He wrote that this case may be indicative of the need for a “reconsideration of the test for Aboriginal title as it relates to coastal First Nations.”

“That would be for a higher court to determine,” the decision said.

The land claim was the first to be heard since B.C. passed legislation in 2019 to align its laws with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

It was also the first case since the landmark 2014 Tsilhqot’in Aboriginal title decision by the Supreme Court of Canada, which recognized the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s rights and title over a swath of its traditional territory in B.C.’s central Interior, not only to historic village sites.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.