You’d be forgiven for having trouble placing the Korean War. It remains Canada’s most intense conflict in 60 years – the total of 516 Canadian dead is more than three times the toll from Afghanistan – but at the time it was overshadowed by the larger scale of the Second World War.

It was a UN mission but a Cold War conflict – one that took sides straightforwardly. (It certainly wasn’t peacekeeping, at least as Canadians like to visualize it.)

Profile: A Canadian hero of the Korean War

It didn’t end in a peace treaty – just a ceasefire that continues to this day .

And for many years it wasn’t even referred to consistently as a war – something veterans, remembering frozen trenches, shelling and nerve-wracking overnight infantry patrols, resented.

“It was just called the ‘Korean conflict’ for a long, long time,” says Calgarian and Korean War veteran Roly Soper. “The veterans didn’t think much of that at all.”

“It used to be a situation where nobody talked about it – that’s how it came to be called the ‘forgotten war’.”

Soper was in combat in Korea as a rifleman in Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in late 1952. He recalls a conflict that echoes the trench warfare of 1914-18.

“While we were there, there was the heaviest mortar bombardment of our lines of the war, as far as the Commonwealth Division was concerned. It was horrific – I have memories that I will never be able to erase. It was incredible, not only from the noise, which was incredible when a barrage set in, but of course from the fear of being hit, even crouched down in a trench, or taking refuge in a bunker.”

Troops patrolled at night, propelled by a life-or-death need to know what was going on out in the darkness in front of the trenches, where both sides waged a ruthless silent battle. Reconnaissance and standing patrols were “every night,” Soper said.

“We would have somebody out on a feature in no-man’s-land somewhere, we would run telephone wire out to some location in no-man’s-land, and go out after dark, and come back before first light. The Chinese did the same thing.

When the darkness was lit with the eerie light of a parachute flare, the soldiers were forced to stand still; any motion would draw unwanted attention.

“There we were, standing like statues in the light. If the flare dimmed out and another one went up, we had disappeared. That happened a lot.”

The Department of National Defence dealt with Korean casualties much as it had their World War Two counterparts: typed casualty lists released to the press with hometowns and addresses of the dead and wounded – “The Minister of National Defence announces with deep regret the following casualties,” they invariably began. “The next-of-kin have already been notified.”

Most Canadians left the experience of war behind in 1945. But for the hundreds of households that received a dreaded telegram announcing a death from combat, wounds, accident or some other twist of fate – three sailors, at different times, were lost at sea and presumed dead – it was still painfully immediate.

Soper made it back in one piece, returning in March, 1953.

“I feel lucky, yes,” he says. “The survival rate was pretty good, mind you, but nevertheless the fear was there.”

But the now-85-year-old was haunted by the war for years.

“One night on weekend leave at my parents’ home I experienced a horrendous nightmare: Chinese Communist soldiers swarmed my trench. In my dream I was alone and leaped out of the trench. In reality I leaped off the end of the bed, hurtled through the curtain-covered bedroom window and landed on the lawn (fortunately a ranch-style bungalow!). I have a jagged scar on one leg as a memento. Nightmares were frequent for several years then eventually faded away.”

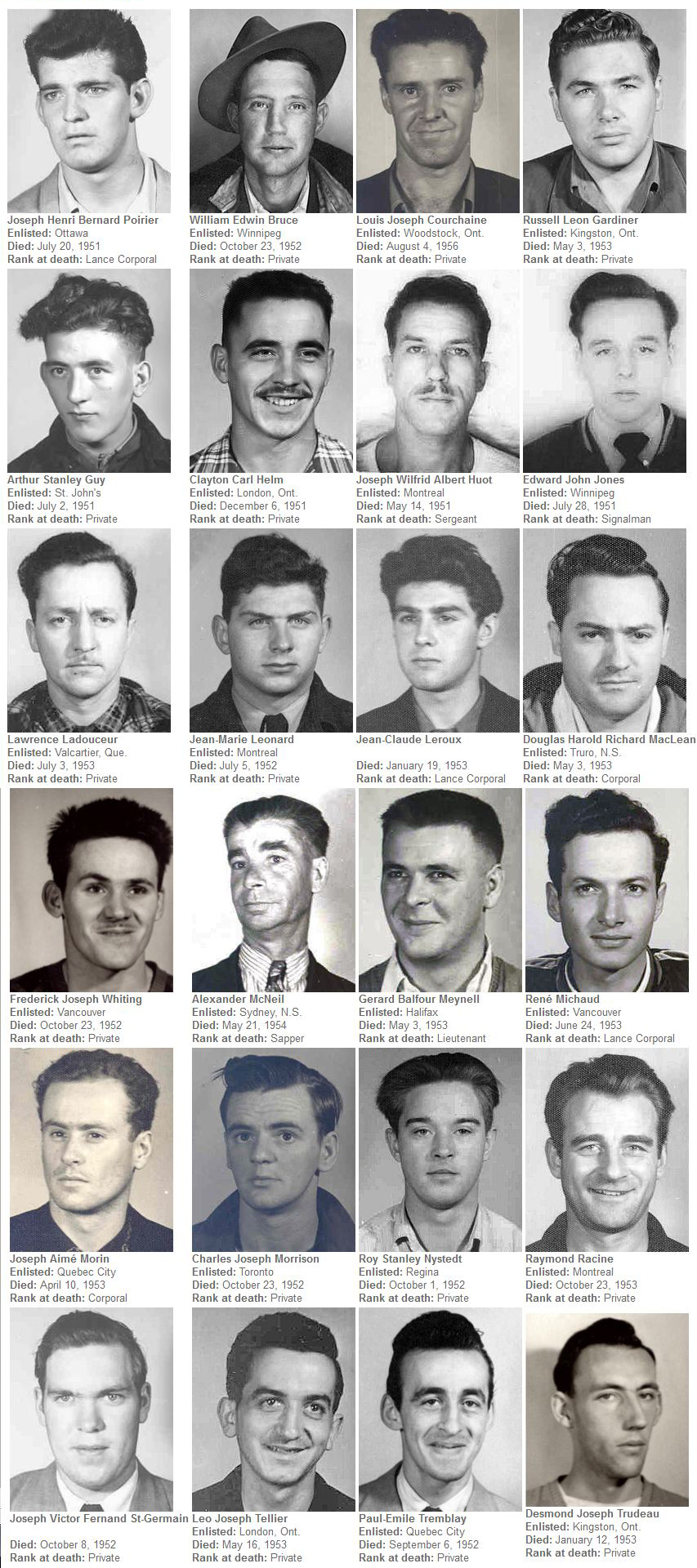

Using casualty lists published at the time and Veterans Affairs Canada’s Virtual War Memorial, Global News has mapped the home towns or addresses of 474 of Canada’s Korean War dead – more than 90 per cent of the total. The 42 we can’t place are listed here with a summary of what we do know – if you have information on any of these individuals, please get in touch.

Newfoundland

Eighteen of the casualties we mapped hailed from Newfoundland, which had become part of Canada just a few years before.

Maritimes

Quebec

Ontario

Manitoba and Saskatchewan

Alberta

BC

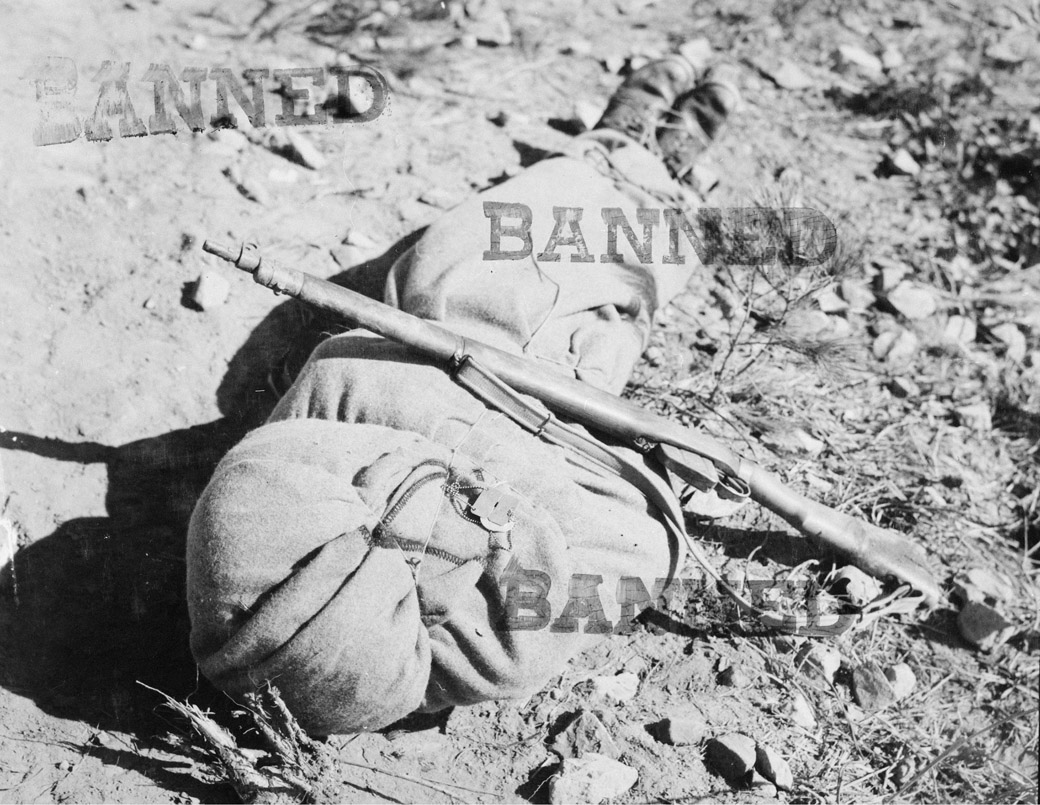

Gallery: Images of Canadian soldiers in Korea burying and remembering their dead

Enlisted

Many of these images of men in civilian clothes enlisting to serve in Korea were taken at recruiting offices as the army expanded in the summer of 1950. All died in Korea, or in Canada from wounds suffered overseas.

VETERANS AFFAIRS CANADA

Comments