After months of fundraising and planning, London’s historic Fugitive Slave Chapel began its slow journey on Tuesday to Fanshawe Pioneer Village (FPV), its new permanent home.

The hours-long move began around 9 a.m., with the 174-year-old structure positioned onto the back of a large flatbed truck for the long trip from Grey Street, in London’s SoHo neighbourhood, to the city’s northeast end.

From there, the truck carefully navigated the small, single-storey building through the neighbourhood, under low-hanging power lines, and onto Hamilton Road, where it continued eastward before turning north onto Highbury Avenue around the noon hour.

The trip through the east end of London was expected to continue through most of the afternoon, with the chapel turning east onto Fanshawe Park Road from Highbury, and continuing on toward the rear entrance of Fanshawe Pioneer Village.

Once settled in at the village, the chapel will be readied for the winter months, and in the spring, will be restored to educate future generations. Officials have said they hope to have it opened to the public sometime in the summer.

Speaking with Global News before the move, Christina Lord, a member of London’s Black History Coordinating Committee and the FPV’s board of governors, said the move was the result of “a lot of hard work by a lot of wonderful people.”

“It really does take a village to get this all done,” Lord said.

It’s the second time in less than a decade that the chapel has been lifted from its foundations and carted off to a new location.

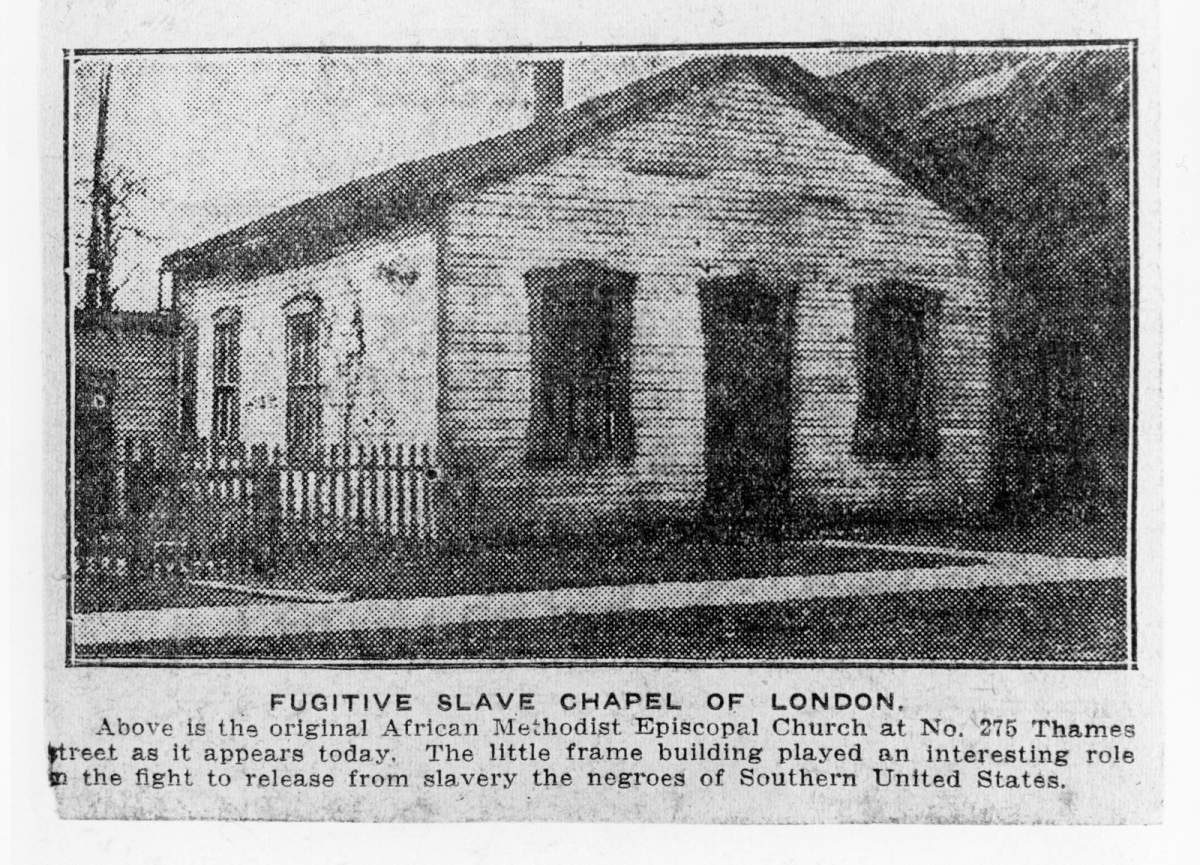

Originally erected in 1848 at 275 Thames St., the chapel, originally the African Methodist Episcopal Church, served as a sanctuary for African Americans who had escaped slavery in the U.S. through the Underground Railroad, and who had built homes in what is now SoHo.

Get breaking National news

In 1856, the chapel became the British Methodist Episcopal Church, and was replaced 13 years later by a new building on Grey Street, according to the London Public Library.

For decades, the former chapel remained on Thames Street, where it served as a private residence until 2013, when it was threatened with demolition.

A community-led effort succeeded in getting the building moved by truck to Grey Street in November 2014, next door to the church that had replaced it nearly 150 years earlier.

“Many of the folks who were part of the original conversations are on the steering committee, as well as some additional people from Black Lives Matter and Congress of Black Women, and of course, from Fanshawe Pioneer Village,” Lord said.

It was August of last year when the chapel’s owner, the British Methodist Episcopal Church of Canada, began talks with the village to gift it for relocation and preservation.

A fundraising campaign was launched earlier this year to help finance the move, with a $300,000 goal.

“We certainly are very, very grateful to our community because we’ve had some amazing contributions,” Lord said.

“We’ve received a lot of support in terms of folks on the ground helping, making some real big decisions. Many of the historians in London who have contributed as well as outside of London, some of the other Black organizations outside of London have also contributed.”

The campaign has seen several major contributors, including $5,000 from the Diocese of London, $50,000 from London-based Ironstone Building Company and $50,000 from Drewlo Holdings.

In April, city politicians endorsed a move to have city hall provide a $71,000 grant to the initiative through the municipal Community Investment Reserve Fund. Last month, the campaign passed its fundraising goal with the help of a $150,000 grant from the federal government through the Canada Cultural Spaces Fund.

Those involved with the project have said the chapel will allow for a different narrative about London’s past than what has been seen at the village previously, highlighting the contributions of the Black community in London, including before the city was incorporated.

FPV officials have said the museum is working with members of London’s Black community to “develop interpretation which will include the history of the building and London’s involvement in the Underground Railroad, as well as commemorating the region’s diverse Black histories.”

“Not only will it be that space that was used originally as it was as a chapel for the enslaved people who had escaped from the U.S., but it will inform a lot of the other programming … to help us understand the history of the Black communities in and around the London area over the years,” Lord said.

“It will give … a great opportunity for particularly our younger generations to learn more about the history of either where their families have been from, or where they themselves have recently come to.”

— with files from Devon Peacock

Comments