By

Elizabeth McSheffrey

Global News

Published October 11, 2022

13 min read

From the age of 30, Angela Mock knew something was horribly wrong inside her.

The Port Coquitlam, B.C., resident was living in excruciating pain that, by 2020, had taken both her and her husband away from work to care for her and their three kids. Bedridden for days at a time, Mock said she had “constant burn marks” from the heating pad she carried everywhere.

“Bladder, lower back, lower abdomen, lots of bowel pain … I felt like someone was constantly stabbing me from the inside out,” she recalled.

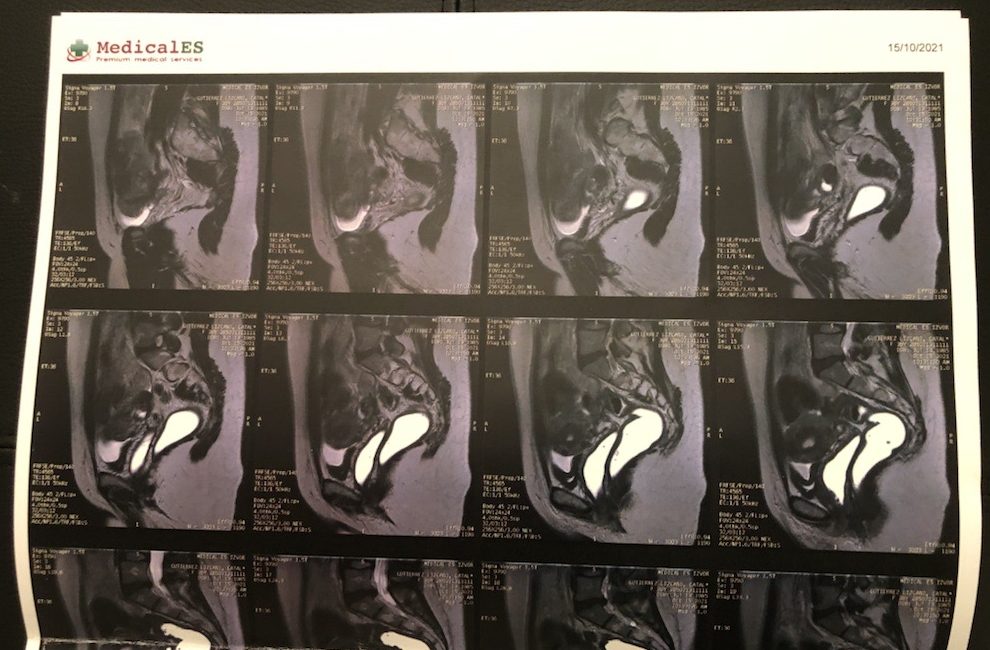

An MRI would later reveal her endometriosis had progressed, consuming her pelvic organs to the point where only “about three millimetres” of healthy colon tissue remained.

She said she was told her bowel could rupture and that her colon needed to be removed – the words “irreversible” and “colostomy bag” ringing in her ears.

“I knew it was bad. I didn’t know it was that bad at that point … it was a very blunt conversation.”

Mock didn’t want to accept that as her only option. Someone suggested she search for an alternative outside Canada, and after consultations with clinics in Germany, the U.A.E., the U.K., and the U.S., she settled on one in Romania.

The Bucharest Endometriosis Center was well-reviewed by other patients in Facebook groups dedicated to information-sharing about the disease, and Mock was on a plane a month later. Her six-hour operation in 2021 included five surgeons at an out-of-pocket cost of $9,500, plus about $3,000 in meals, accommodations and flights.

“He removed over 30 different endometriosis masses inside me. He worked on my kidneys, my bladder, my ovaries, my sacral roots, my rectal wall, and obviously, my bowel,” Mock said.

“I know it sounds dramatic, but he literally saved my life.”

There is no cure for endometriosis, but more than a year after the complex procedure, Mock said she feels “like a new person.”

She’s not alone: Every year, nearly 100 Canadians scour social media, conduct online research, and, in many cases, fundraise to fly to the clinic in Romania for surgery.

Global News reached 22 women living with endometriosis across the country, 12 of whom have been treated in Bucharest. They cited unbearable pain, long waitlists, and a history of having their pain dismissed as among the reasons that drove them abroad.

Top endometriosis experts in Canada have acknowledged there’s a problem, and while there’s no quick fix in an overwhelmed health-care system, they said they’re confident continued advocacy and resource-sharing is fostering change in a society that has long stigmatized and failed to adequately educate on reproductive and sex-based health issues.

Endometriosis is a painful and complex disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus implants outside the uterus, forming lesions, cysts and other growths. It most often impacts the ovaries and fallopian tubes, but has been found on every pelvic organ and surface, and, in rarer cases, outside the pelvis — even on the brain and lungs.

The growths can lead to swelling, bleeding, scar tissue and adhesions that can bind the body’s organs together. This can lead to excruciating periods, painful bowel movements and urination, pelvic pain, back pain, bloating, nausea, fatigue, infertility, and complications in mental health.

“I was trying everything. I was doing acupuncture three times a week, I was on CBD, I was doing chiro, I was doing physiotherapy,” said Mock.

“It was the most pain I’ve ever been in in my entire life … every day, I’d have a nap for three, four hours and then be in bed by 9:30 p.m.”

Endometriosis affects one in 10 women and an unknown number of transgender and gender-diverse people – more than a million Canadians altogether. For many, pain begins at menstruation, but a recent study published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada found the average patient is around 28 years old by the time the disease is properly identified.

Edmonton’s Trina Wagner was 44 when she was finally diagnosed, having been told by different physicians over the years that her pain was from gas, a hernia, depression, and a “nervous stomach.”

The pain was so severe, she added, that she visited the emergency department a dozen times one year, paying $385 for an ambulance each time because she was too incapacitated to drive.

“It was very demeaning,” Wagner said. “It just makes you feel less-than, like you’re not important and your pain is not legitimate.”

When Mock obtained her B.C. medical records, she said one doctor had written that the pain was “in the patient’s head,” and suggested it was “PTSD” from her hysterectomy in 2017.

Natalia Forero of Cambridge, Ont., said she was “gaslighted” many times before receiving a diagnosis at 42, with one physician recommending she read a “mind over matter” book after insinuating the pain was psychological.

“I have a huge respect for doctors, and when someone that you respect so much is telling you you’re wrong, (that) this is all in your head, you actually think it’s in your head,” she said.

After a while, Forero said her husband’s reaction to her suffering was the only thing convincing her the symptoms were real – whether it was urination so painful, it reduced her to tears, or a stabbing pain up her back every time she took a deep breath.

Both Wagner and Forero said they were told the waitlists for excision surgery – which cuts out the problematic growths at the root, rather than scraping them off at the surface – were more than two years in their provinces. Instead, they opted for Romania.

In June, Wagner had excision surgery for growths throughout her pelvis and a colpopexy for a collapsed bladder. With flights, meals and accommodations, she paid about $15,000.

Forero had a hysterectomy and excision surgery in November. She paid about $11,500 altogether – half of the down payment she and her partner had saved for a house.

“I’m not used to begging for health care, even coming from a third-world country,” said the Colombia native.

“We left behind loved ones, the comfort food and the nice weather because we have been promised better quality of life in Canada, but Canada, you are not keeping your promise.”

According to its website, the Bucharest Endometriosis Center performs about 400 surgeries per year. Canadians make up a staggering 30 per cent of the caseload – between seven and eight patients a month, according to founder Dr. Gabriel Mitroi.

By email, Mitroi said he believes the “lack of proper endometriosis care is a global problem, not specific to one country.”

“A general myth still persists that endometriosis is not a complex disease. Most physicians prescribe hormonal therapies, which are marketed as a solution for endometriosis,” he said.

“I think it all starts in medical schools, where outdated information about endometriosis is taught.”

Global News interviewed patients in B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario and Nova Scotia. Many said they were told they simply had “normal period pain.”

All 22 people said they have received medical advice or non-surgical treatment they considered unhelpful. They gave mixed reviews on hormonal therapies. And they described remedies such as yoga, laxatives, weight loss, over-the-counter painkillers, and even getting pregnant to reduce the symptoms for nine months, as ineffective or not relevant.

Global News requested comment from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, or SOGC, and was referred to Dr. Sukhbir Sony Singh, chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology and newborn care at the Ottawa Hospital.

Singh said he was “never really taught” about deep or complex endometriosis – his specialty – as a medical student or resident. While most of his physician peers have “some working knowledge,” it will take years to change the system at large, he added.

“I sought a lot of my training after completing my original training in Canada as well as Australia to be able to develop that skill set,” he said, a day before leaving for the annual conference of the Canadian Society for the Advancement of Gynecologic Excellence in Halifax.

“Education within our system is definitely lacking.”

Global News contacted eight of the top-ranking medical schools in Canada to gauge what formal exposure their undergraduates have to endometriosis.

Of the seven schools that responded, five confirmed all students learn about it – in at least one lesson – as part of regular curriculum. McMaster University in Hamilton responded with an additional commitment to review its curriculum for opportunities to improve.

Even after specializing in obstetrics and gynecology, Dr. Mathew Leonardi, an assistant professor in McMaster’s medical sciences graduate program, said few physicians in Canada have the skill set to diagnose endometriosis through diagnostic imaging – something he trained on for two and a half years. Often, the disease is diagnosed instead through a laparoscopy, which allows a surgeon to access the abdomen and see the growths first-hand.

Both methods are subject to human error, however, and diagnostic imaging may not detect the mildest, superficial form of the disease, he said.

“If we can improve (the diagnoses), I think that’s going to be a major game-changer,” said Leonardi, who is also a gynecological surgeon with Hamilton Health Sciences.

For more than two years, COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on health-care systems in every province and territory. Waitlists that were already long became longer, driving endometriosis patients like Kolbi Morley to consider shelling out thousands for quicker treatment abroad.

“I’m 33 and fertility is on the line,” the Halifax resident said. “Some women wait over a year to see a gynecologist and then however long to get a surgery.”

Morley has paid out of pocket for remedies not covered by public health care, such as pelvic floor physiotherapy and naturopathic medicine. She’s currently on extended sick leave from her hospitality job due to “24/7” pain in her pelvis, back and hips – pain so intense, she sometimes wonders whether her appendix has ruptured or a cyst has burst.

“You go to the emergency room and they just tell you to basically go home and take some painkillers … there’s nothing anyone really will do until you get in to see the specialist or until your surgery. You’re just kind of like a guinea pig on meds.”

Atlantic Canada’s first multidisciplinary endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain clinic is now up and running at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax, but its lead physician, Dr. Elizabeth Randle, said the waitlist is at least a year. Every effort is made to speed up the process for those in urgent need, she added, but the disease can get worse the longer a patient waits.

“It’s not uncommon for patients, by the time they are being seen by specialty and subspecialty physicians, to have more extreme presentations,” Randle explained.

“This type of complex disease process really does require a team of specialists who can approach it to manage it in the best way … We definitely need more of everything in order to be able to provide the care that we’re seeing the demand for.”

Singh said he respects a patient’s choice to go abroad if they can’t get timely treatment in Canada, but worries about them getting proper follow-up care for a condition that necessitates a “lifelong relationship” with the health-care system.

Endometriosis costs the health-care system an estimated $1.8 billion each year.

More resources for education, training and care – including dedicated operating room hours in hospitals – are needed, patients said, as well as more compassion and validation from doctors.

Catalina Lizcano, who lives in Montreal, said she advocated for excision surgery to treat her debilitating pain for years, but was told cryptically by several physicians there was “no point” unless she planned on having children. She said she also lost a job because of how much time off she took to manage her symptoms, and would like to see endometriosis recognized as an “illness that causes disability,” with protections in the workplace.

“I reached the point of being in pain three weeks out of four,” Lizcano recalled.

“I was calling in sick so often at work, I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t walk my dog, I couldn’t cook … I could do nothing other than try to keep going.”

Both Singh and Leonardi said they – and others in the field – are working to change a culture that has historically sidelined and stigmatized the health concerns of female, transgender and non-binary patients, but everyone has a role to play.

“To hear these stories breaks my heart … I hear this every single day in my clinical scenarios,” said Singh.

“The responsibility lies among all of us. The patients are speaking up – fantastic. I need to speak up. The SOGC needs to speak up.”

In his own practice, Leonardi said he now adds a line at the end of a patient’s report that says something like, “Just because today’s ultrasound is normal doesn’t mean the patient is normal … and this should not be the last point of investigation or validation for the patient.”

The SOGC, meanwhile, is developing a new endometriosis guideline, and the Canadian Association of Radiologists is working on a consensus paper to advance awareness and education for members.

Last year, Ontario’s Bill 273 formally declared March as Endometriosis Awareness Month, and this year, Vancouver-area MP Don Davies introduced a private members’ motion in the House of Commons calling for a national action plan. Australia has such a plan, and similar strategies are being discussed in France and the U.K.

“It’s time to put the focus and the resources and the finances behind funding endometriosis awareness (and) endometriosis support,” said Kate Luciani, executive director of The Endometriosis Network Canada.

“The trickle-down effect – we hope – means faster access to surgery, faster access to care, (and) getting this care in places that you don’t normally get it.”

Speaking to Global News, federal Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos did not say whether Ottawa would consider a national plan, but that it wants to continue listening to patients and researchers.

“Obviously, a lot of that responsibility falls in the domain of provinces and territories because it deals with the provision of health-care services. When it comes through the data and analysis of research, the federal government has an important responsibility to keep the capacity.”

Health ministers in Alberta and Ontario did not respond to requests for comment by deadline. Nova Scotia’s health minister declined a request, and B.C.’s health minister was not available.

More than a year after her successful operation, Mock encouraged governments to consider how other countries treat endometriosis with a mix of public and private services.

“It’s great that we have free public health care, but we should be able to have a choice,” she said.

“This could be prevented in really, really young ages of women and teens, and it is something that should be more carefully looked at and funded in our medical system.”

Mock said she knows that even after her surgery in Romania, there’s a chance the endometriosis could resurface. Until then, however, she will enjoy her new quality of life – with a new memory to overshadow the words “irreversible” and “colostomy bag.”

“I had my first shower after the surgery and it was like, the most amazing one ever,” she said with a smile. “I just stood in there and I was just sobbing because I felt like finally, somebody took me seriously and did something about it.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.