By

Ashleigh Stewart

Global News

Published September 24, 2022

38 min read

The day before the stabbing rampage at James Smith Cree Nation, Damien Sanderson’s wife, Skye, called 911 to report her husband.

He had taken her car and was high and drunk, driving around the tiny Saskatchewan community with his brother, Myles, lurking around her father’s house and trying to intimidate him.

She believed the only way to stop them from doing something “stupid” was to get them both locked up.

“I was trying to save my husband from his brother. I knew that wasn’t my husband.”

But, she says, her pleas fell on deaf ears. RCMP members arrived and returned her car to her but didn’t do enough to locate Damien and Myles — despite the pair’s outstanding arrest warrants.

Twenty-four hours later, on Sept. 4, 10 people were dead, 18 people were injured, and the Sanderson brothers were prime suspects in one of the worst mass killings in Canada’s history.

Skye believes the RCMP failed her and her community. If they’d been more responsive to her call, she says, James Smith Cree Nation (JSCN) would not be in mourning.

As the community struggled to understand the senseless violence on their doorsteps, one of the victim’s families invited Global News to spend time in JSCN. We were there when the sacred fires were lit, loved ones were buried and the population swelled with well-wishers from across the country. In the days since, we have attempted to piece together the details of that night and the events leading up to it alongside the community.

For many, like Skye, this is the first time they are speaking openly about what they witnessed that night. They describe an early morning frenzy where nobody was spared, young or old, from Myles’s rampage. Damien is notably absent from most accounts.

Many believe Damien has been miscast in his role in the murders. His body was found at the crime scene, while Myles’s escape sparked a four-day manhunt before the RCMP apprehended him and he died in police custody. A common refrain is that Damien should be counted among the victims.

“Damien wasn’t a threat to society. He was a family man,” JSCN Chief Wally Burns says.

Both brothers had run-ins with the law. Myles had racked up 59 convictions by the age of 31 and was already a wanted man when he committed the murders. Damien was, too; there were two outstanding warrants for his arrest for assaults in 2021 and 2022. Both had issues with substance abuse and violence toward their partners

But, Skye says, Damien was working to overcome his demons. There was just one bad habit he couldn’t break free from: his brother.

“Myles took Damien away from me,” she says.

“Damien was afraid of his brother. He really was. Because he was unpredictable.”

It all started going downhill two months ago.

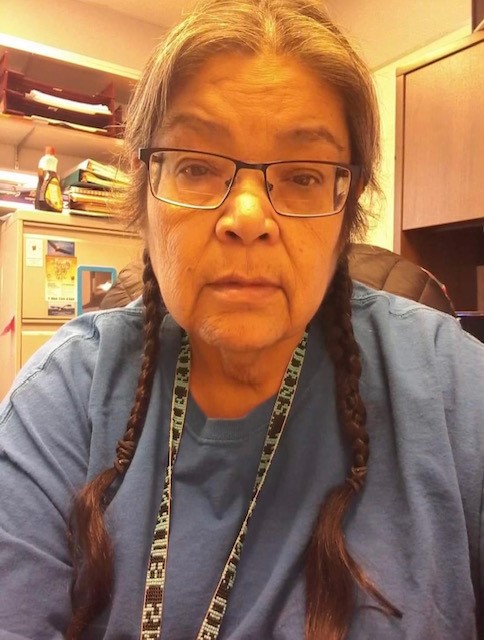

“I want to start from the start,” Skye Sanderson says with a deep breath.

Her voice is steady. She is sitting on the couch in her new home in a town nearby JSCN, which she doesn’t want to name. Every so often, her two daughters, aged 14 and five, appear at her side, demanding their mother’s attention. Her 10-year-old son is staying with his grandmother.

Even with the distance that her new home has brought, she isn’t sleeping well. She is worried about the cost and burden of raising three children alone. She’s been receiving death threats and vicious insults about her husband’s role in the murders. She’s considering keeping her children home from school indefinitely, worried that they’ll be harassed about their father.

She is finally ready to speak, she says, because her husband was not the monster people have depicted. She’s concerned about the impact this narrative is having on her children. Her five-year-old daughter is autistic and has intellectual disabilities. Her 10-year-old son found out his father died from a TikTok video.

She takes another deep breath.

“Damien never had a relationship with Myles. But around two months ago, Myles started wanting to come to the reserve,” she says.

It was shortly after Myles had been released from prison — again. He’d been granted a statutory release in February after serving a four-year sentence for assault, assault with a weapon, assaulting a police officer, uttering threats, mischief and robbery.

Myles had racked up 59 criminal convictions at that point — many for assault. He was only 31.

The brothers stopped talking during Myles’ 2018 incarceration. Damien had grown tired of Myles calling and asking him for money.

“But then he was released. And all of a sudden, he was calling Damien to check up on him every day. Damien was kind of getting sick of it. He wasn’t used to being checked up on by his brother because his brother never cared,” Skye says.

“Then he started showing up at our house, unexpectedly and unwelcome.”

Skye had always gotten a “bad vibe” from Myles. She describes him as “dangerous and hateful.” She recalls making her children’s lunches, or doing the dishes, as Myles watched from across the room in a “creepy way.”

“He creeped Damien out, too. Myles came down the first time saying that they were going to go hunting, do brotherly things and everything.

“But that wasn’t the case. He came down and he started feeding my husband cocaine. And then he asked Damien if he can go sell this s–t for him to drug-deal and make money and all that.

“And my husband got hooked right away.”

Skye and Damien had their own substance abuse issues. Skye says her husband had battled anxiety and had been hooked on pills to deal with it. She suffered from depression after being sexually assaulted when she was young and was on “five pills a day to make me feel normal.” They both used drugs and drank too much.

“But we were on the road to recovery. We were trying really hard.”

Earlier in the summer, during a drug-and-alcohol binge at their house one night, Skye retreated to the bedroom because Myles’s behaviour was making her uneasy. Damien followed her soon after. He was worried about some of the things his brother was saying about his common-law spouse, Vanessa Burns.

“Damien said, ‘I get the feeling my brother’s like the devil or something.’”

Damien told his wife that he worried Myles would try to target her, too. They stayed up for hours, listening to Myles as he approached their bedroom door and walked away again.

Eventually, Myles left for Saskatoon, where he was in an on-off relationship with his common-law spouse, Vanessa Burns. A man who lived next door to Myles in Saskatoon for a year — who did not want to be named for fear of repercussions — said Myles was frequently abusive and intimidating toward him for no reason. He often heard Myles and Vanessa fighting.

“Vanessa was a really lovely girl but she was so intimidated by that guy. She said to me that she couldn’t talk to me, because if she did, Myles would kill me,” the man says.

Myles returned to JSCN about three weeks after that visit, Skye says, again selling drugs around JSCN and set on emotionally manipulating his brother. He would cause fights between the couple and urge Damien to leave his wife. Myles brought his brother crack cocaine and Damien smoked it with him, “because he felt like he had to.”

Skye says she reported Damien to the RCMP several times for being violent towards her, but he was never arrested. But he wanted to get better.

“The night before Myles came down, we were talking about getting help.”

As well as anxiety, Damien battled with overthinking and had constant negative thoughts. He started working with Gloria Burns, an addictions counsellor at JSCN, and described her as the “coolest counsellor he ever met,” Skye says, her voice breaking. Gloria would later be among the dead.

“That hurts me because she worked with our family. We went to a family trip to Tobin Lake, and we told her our secrets, and she told us her secrets, and she told us it was safe with her, and we don’t have to worry about anything.

“But he didn’t f–king come home.”

Located northwest of Melfort, JSCN is a small community on the Saskatchewan River. It’s a sparse stretch of arid land and wheat fields, bisected by gravel roads. In September, combine harvesters trundle up and down the roads between fields, kicking up dust. At night, the dust clouds hang in the air like fog.

The territory is shared between three first nations: JSCN, the Peter Chapman First Nation and the Chakastaypasin First Nation. The on-reserve population is estimated to be about 1,900 members. Many share one of a handful of last names — Sanderson, Burns and Head among the most common.

It was here that Skye and Damien met when she was just 14, he was 15. Skye, a Head; Damien, a Sanderson.

They were forced to grow up quickly. Skye became pregnant and they had their first child, a girl named Cora, a year later.

Damien had a difficult upbringing. When his parents, whose marriage was troubled, separated and his father moved to Saskatoon, he lived between his mother’s and grandmother’s houses. After Skye and Damien got married, when she was 19, Beverly moved in with them.

Skye was close with her family. When the couple married in 2012, Skye’s father, Christian Head, was in prison for assault and wasn’t able to give her away. He was incarcerated at the same time as Myles and upon both of their releases, Christian helped Myles get into a healing lodge he was going into to seek help.

Christian returned home a changed man, Skye says, and their relationship strengthened. Myles, however, did not appear to have changed.

Christian was also among the dead on Sept. 4, killed in his home alongside his girlfriend Lana.

“My family loved and adored Damien. That was Damien’s family, basically,” Skye says.

Two more children followed — a boy, Deighton, and a girl, Lilliana.

Damien left school and got a job at 15 to provide for his family. He worked odd jobs, labouring and contracting mostly. But he could never quite get away from his brother. When he wasn’t in prison, Myles would show up out of the blue to try to drive a wedge between his brother and his family, Skye says.

“Myles was out messing around and doing whatever he wanted. Damien was a family guy that always stayed with his wife, was always with his kids.”

Around JSCN, people remember Myles as a dangerous guy, someone whom people tried to avoid. He had committed many of his assaults at JSCN or on its members. His violence towards Vanessa was well-known.

But members speak openly of their affection for Damien. Many whom we interviewed at JSCN recall him as an active member of the community, a family man.

“Damien was a very passionate man. He worked and was a very active band member,” says Chakastaypasin Chief Calvin Sanderson.

“He liked to hunt and to do outdoor activities.”

Pictures uploaded by Skye of her husband on Facebook show him holding his children, baking with them in the kitchen, and cuddling his wife.

The couple celebrated their 10-year wedding anniversary on Aug. 31.

“Have a great day everyone. Feels good to be back at work and the kids’ first day back at school.”

Four days later, all hell broke loose.

Damien and Skye were babysitting Myles and Vanessa’s four children. That Friday, Skye was taking a nap when one of her nieces started yelling for her to wake up and help her Mum. Outside, Skye saw Myles beating up Vanessa on the road. She had two black eyes and a lump on her head.

“He was trying to run her over with her vehicle. So I woke up Damien.

“So he gets up and he goes out and his brother was, like, trying to fight him … getting mad at Damien, like, ‘Oh, you think you’re so much f–king better than me all the time. You’re just protecting these f–king bitches.’”

Damien put Vanessa in her car and locked the doors as his brother ran around the outside, trying to find a way to grab hold of his wife. Vanessa drove off. Damien came inside the house to tell his wife that he was going to take Myles away for a while. He didn’t say for how long.

“He said, ‘Babe, I’m going to take my brother to cool off. He’s mad.’ I said, ‘Okay then.’

“Then I said, ‘F–k, I hate when their problems become ours.’ And he said, ‘I know, right?’

“And that was the last time I ever saw my husband. He didn’t come back.”

Skye breaks down as she recalls the events of the next two days. At some point during the day, Damien stopped replying to her messages asking where he was and when he was coming home. Witnesses later told her that both brothers were high and drunk for most of that weekend.

“Then my husband turned against me. He was out looking for me,” she says.

That evening, Damien and Myles began driving around, intimidating people. They drove slowly past where Skye’s father, Christian, lived with his girlfriend, Lana Head. Skye asked her sister to watch her son, who has ADHD. She worried the brothers would come for her.

On Saturday at 4:30 a.m., she says she called 911 to report Myles and Damien.

An RCMP car showed up and asked her where the brothers might be. She told them that he was hiding, to look around the territory. The RCMP soon located her car at a friend’s address. Members searched the house and returned her car keys, but they found no sign of Damien or Myles. Skye says she pleaded and begged for them to look harder, but she says they didn’t.

The RCMP declined to answer questions about this visit. However, Skye’s niece Samara Stonestand, who was at the house at the time, confirmed they were there and did not locate the brothers.

Later, Samara gave Damien and Myles a ride to pick up more alcohol. Damien told her that, when confronted by police inside the house, he gave RCMP his cousin’s name. The picture on his arrest warrant was outdated — he’d gained a lot of weight since then.

Skye gave up searching for him.

“So I went and stayed at my friend’s house. Damien still wasn’t coming home. He was texting me some stuff. Like ‘I’m going to do some s–t with my brother.’… His brother was putting s–t in his head.

“He said, ‘I have nothing to lose.’”

Damien and Myles were no strangers to the law.

At the time of the murders, Damien had two outstanding arrest warrants for assaults against unnamed victims — one in August 2021 and one in June 2022. Skye says she filed a raft of reports for domestic violence, but police usually did not make an effort to arrest him.

Myles, on the other hand, had a hefty court file — a catalogue of violence, second chances and missed opportunities.

His parole documents detail a troubled upbringing bouncing between homes and being exposed to violence, drugs and alcohol at a young age. He started drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana at age 12 and began using cocaine at 14. He said his regular use of hard drugs and alcohol made him lose his mind. He may have been a gang member at one time, the documents state.

Seven of Myles’ charges were for assaulting Vanessa. A week after one of his attacks on her in 2015, he allegedly tried to stab her father, Earl Burns Sr., to death. He also attacked her mother Joyce Burns. Earl Burns Sr. was among those killed on Sept. 4, and Joyce Burns was injured.

Upon his release from the two-year sentence for assaulting Earl and Joyce, he stabbed two men, beat one of them unconscious and, when he was being arrested, fought with police. That earned him a 569-day sentence.

Together with other crimes he committed around that time, his sentence came to over four years. But he was freed on statutory release in August 2021.

The Parole Board said in a statement that statutory release was mandatory after offenders had served two-thirds of their sentence.

Three months later, he was locked up again for violating the terms of his release.

While he was inside again, though, he was allegedly planning his next attack.

Brian “Buggy” Burns, a member of JSCN, said he had a friend who was imprisoned with Myles. The inmate said Myles had talked about a revenge killing before he was released. His target was Earl Burns, Sr., he said.

Earl was helping to raise Myles and Vanessa’s four children. Myles also had an older child with a different woman, whom he did not see. Vanessa declined to be interviewed for this story.

Skye says Earl was desperate to protect his family from Myles.

“He never got along with Earl. Myles was never in the picture and Earl did most of the raising of the kids,” Skye says.

But Calvin Sanderson, the Chakastaypasin Band Chief, says Myles had tried to turn his life around about a year ago.

“Myles had his issues, he didn’t contact me so much. When he was going through a few incidents, he phoned me and said he was trying to change his way of life. He was doing well for a while and was trying to be a good band member. He sounded genuine. And he made many attempts to try, but he must have relapsed.

“Maybe the system failed him. I don’t know.”

There was some rivalry between the two brothers. Myles was jealous or bitter toward his brother because he seemed to have his life together, Skye says. Damien repeatedly tried to help Myles, to try to get him to straighten himself out. But it never worked.

“He should’ve known already that he couldn’t fix his brother. He tried so many times.”

The Parole Board released Myles in February on the basis that he would “not present an undue risk,” to society. Upon his release, Myles was prohibited from consuming alcohol or drugs. He also had to follow a treatment plan, avoid his victims and their families, and refrain from contacting his children a person identifiable only as “V.B”.

By spring, Myles had stopped communicating with his parole officer, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. For most of that time, Skye says, Myles was hiding in plain sight, driving between JSCN and Saskatoon.

On Sept 3, the day before the murders, Skye didn’t hear from Damien. Eventually, after making her children dinner, she went out to a bar with her dad, Christian, and his girlfriend, Lana. She left her phone at home for her eldest daughter to use because they’d run out of WiFi.

Around that time, Damien and Myles reportedly beat up 28-year-old Gregory Burns in an alleged random act of violence. Gregory’s best friend, Creedon DiPaolo, says Myles had sent Gregory a message saying he wanted to see him. When Creedon dropped Gregory at home, Myles and Damien were waiting across the road. Myles attacked him without warning.

“Gregory was pretty shaken up. He walked back to my car, holding his jaw, saying he would see me later,” Creedon says.

“Then Damien and Myles started walking fast towards my car. They asked me if I was Terror Squad.”

Terror Squad is a notorious street gang based in Saskatoon. Creedon replied that he wasn’t, and the brothers surrounded him in his own car. Damien slid into the front seat, Myles into the back, where Creedon says he threatened him with violence if he didn’t drive.

“They wanted to go find Terror Squad members to beat them up. Myles was high and Damien was drunk. He had a 40-ounce of Wiser’s with him,” Creedon says.

“I felt like they wanted to hurt me. Myles asked me if I was scared and I thought I was going to get attacked.”

Creedon says he had an unopened bottle of alcohol in his car and offered it to Myles, who declined, saying, “If I drink, then I’ll really be plotting to murder someone.”

After about half an hour of driving without finding any gang members, Creedon told the brothers that he needed to go and have a shower and that he would pick them up later. He was lying.

“I didn’t know Myles, but I worked with Damien, and at one stage, I was talking to Damien and I said, ‘I know you’re not like this.’ He replied, ‘When it comes to it, I can be.’”

Meanwhile, Brian “Buggy” Burns, Gregory’s father, received an anxious call from his wife, Bonnie. Buggy was away at a horseracing tournament for the weekend.

Christian, Skye and Lana returned to Christian’s house at about 2.30 a.m. Skye left about an hour later to meet a friend. Around that time, her sister messaged to say she’d spotted Damien and Myles lurking around the reserve again. The pair had already jumped back in their car and driven back into town but ran out of fuel. When her sister said the brothers had disappeared again, Skye went to stay at her friend’s house.

The details of what happened next are hazy. But in the early hours of the morning, Myles went back for Creedon DiPaolo.

Creedon says he awoke at about 4 a.m. to his 65-year-old mother, Arlene, screaming from her bedroom. When he rushed in there, he saw Myles standing over her on her bed and stabbing her in a frenzy. His 11-year-old niece, who was in the room at the time, would later tell him that Myles had knocked at the door, then kicked it down and stormed into Arlene’s room looking for her car keys.

“I went charging at him and then he was trying to stab both of us.

“The last thing I remember was him stabbing me on the side of the head close to my temple. It hit a bone, but if it was half an inch away, I’d be dead.”

Creedon fell to the ground, losing consciousness for a few seconds. In the meantime, Myles had taken his mother’s keys and fled.

Selene Goodvoice, Creedon’s partner, rushed to his side. He had eight stab wounds across his torso and head.

“I was freaking out, crying, trying to stop the bleeding while his nephew was trying to stop Arlene’s bleeding,” Selene says.

Martin Moostoos, another of the early victims, says the brothers showed up at his house around 5 a.m. Myles kicked the door open.

“He punched me and then got some scissors and held them to my neck,” Martin says.

“That guy was out to kill me … just because I owed him $50.”

But that’s when Damien fought his brother off, Martin says, and removed Myles from his house. Outside, they were fighting. Martin was left with stab wounds on his chest and neck.

“If it wasn’t for Damien, I would’ve been dead. He saved my life.

“After he left, I right away called 911.”

The first report of a stabbing at JSCN came into the RCMP’s Melfort detachment at 5.40 a.m. Three minutes later, two members were dispatched to the scene.

Just before 6 a.m., a second call came into the RCMP about two more people injured. The two Melfort police officers arrived at 6:18 a.m.

In total, there were 13 crime scenes. Loved ones were felled alongside each other. Some died trying to protect family members or friends.

Aside from Creedon and Martin’s accounts, most stories and rumours from around the community portray Myles as the sole attacker. It is believed that many of his victims were targeted, related to drug deals or money being owed. Others were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Gregory Burns and Bonnie Goodvoice-Burns were killed in their driveway alongside Gloria Burns, the 62-year-old addictions counsellor Damien once described as the “coolest counsellor he’s ever met” and Bonnie’s close friend. Gloria had been responding to an early-morning crisis call from Bonnie when she was caught up in the attacks.

Shawn Burns, a family friend, awoke around 6:40 a.m. to a private message on Facebook from Buggy’s son Dayson. He said his Mum was gone.

“I went flying down to his house as fast as I could,” Shawn says.

“When I got there, I saw the bodies just lying there and some of the people told me what happened.”

A window in their basement was broken, which is how Myles allegedly gained access.

“The house was so bloody, it was all over the kitchen. They chased Gregory through the house and caught up to him outside. Bonnie went outside to try to help,” Shawn says.

Meanwhile, Dayson, Buggy’s second-eldest son, had locked his two brothers and Bonnie’s two young grandchildren in a bedroom and told them not to come out. He was stabbed in the neck during the frenzy.

Earl Burns Sr, Vanessa’s father, a 66-year-old school bus driver and a war veteran, was attacked in the home he shared with his wife, Joyce. Earl’s four grandchildren were home at the time; Skye had dropped them off that Friday.

Earl’s body was found in his school bus, which had been heading up the hill from the north part of the reserve and had rolled into a ditch.

The circumstances in which the bus was found remain mysterious. Some say Earl was trying to chase Myles down in it. Others say he was searching for help but died from his wounds. Joyce survived the attack but was critically injured and remains in the hospital, fighting for her life.

Twenty-three-year-old Thomas Burns was killed alongside his mother Carol Burns, 46. Carol’s uncle, John Burns, says they lived out of town and were visiting Carol’s father for the weekend.

Christian and Lana Head were found dead in their home. Christian’s sister, who did not want to be named, found their bodies early that morning.

“I was calling him to ‘wake up, wake up please.’ He wasn’t breathing, and I checked and he had no pulse. I sat there beside him crying. I was in shock, I guess.

“Then I saw a trail of smeared blood going towards the bedroom on the floor, like someone was dragged. I went in there and checked and there was Lana, face down in a pool of blood, same as my brother. Her hands were clenched tight on a blanket.

“There was so much blood. My poor little brother. I couldn’t save him. I’m broken.”

Skye’s sister and brother-in-law, who were there too at the time, were among the injured.

The circumstances of the death of the last of the 11 murder victims, Robert Sanderson, 49, are unknown.

By 6:35 a.m., the scale of the tragedy was becoming clear, and the Saskatchewan RCMP prepared to issue an emergency alert. It was sent out at 7:12 a.m.

Saskatchewan residents awoke to a dangerous persons alert after several calls of stabbings on the James Smith Cree Nation by two male suspects. People in the area were urged to remain in place or seek immediate shelter.

The words “chaos” and “war-zone” are those most frequently used by JSCN members recalling what they awoke to that morning. Most say they woke up to calls from friends or family, or the emergency alert. Some rushed to help. Others went looking for the perpetrators.

Selene Goodvoice drove Creedon and Arlene to the band office, where paramedics and STARS air ambulances had accumulated. The RCMP prevented them from going to pick up the wounded because they weren’t sure where the suspects were.

“Once we showed up, people kept coming, they kept coming. They were all stabbed up and people were saying the names of the ones who died. It made everyone cry,” Selene says.

Her grandfather, Earl, was among the dead. So was her close friend, Gregory. Everyone knew someone who had died. The overwhelming outpouring of grief was magnified due to the size of the community; many were related to the victims.

At 7:57 a.m., an updated emergency alert was issued with the names and descriptions of Myles and Damien. Twenty-three minutes later, another was issued, this time with the description and licence plate of their getaway car, a black Nissan Rogue.

Skye didn’t know anything had happened until about 9:30 a.m. She’d left her phone at home. Nobody could get ahold of her.

The RCMP were waiting at her house. Her two daughters were inside and the house had been pulled apart. Her daughters told her that Damien and Myles had been there at some point during the night. Her eldest told her that they kicked down the door and then stormed into Skye’s bedroom.

“Damien said to Cora, ‘Oh, s–t, I didn’t know you were home.’ She said that ‘Dad came and kissed me and Liliana and said, ‘This is probably the last time you’re ever going to see me.’’”

Nearby, the residents of the small village of Weldon, 30 kilometres southwest of JSCN, had woken to a death of their own. Myles had approached the home of 78-year-old widower, Wes Petterson and murdered him as he answered the door. Wes’s 25-year-old grandson was hiding in the basement, from where he called the police.

Weldon residents say the attack was likely random and that Wes would open the door to anyone; he was that kind of person. Some in JSCN say Myles had a connection with his grandson.

Myles approached at least one other house in the tiny village of 300 residents before fleeing. Doreen Lees was sitting outside on her porch with her daughter when Myles arrived.

“This guy came along — he just appeared about 20 feet away,” she says.

“He had a jacket around his face. I could only see his eyes and hair. He said, ‘Can you help me? I’ve been stabbed.’”

Lees’s daughter snuck away inside to call the police. Myles immediately fled.

“I tore after him to see what was going on, to see where he was going and if there was a car. But my daughter called me back,” Lees says.

Lees wasn’t sure if Myles was telling the truth about his injuries: she couldn’t see blood on Myles’s body. But later, the RCMP mentioned there was evidence he’d been seeking treatment for some kind of injury — he’d broken into a car in Weldon and had stolen a first aid kit.

The fourth emergency alert that morning was issued at 10:01 a.m. New photos of the brothers were released, the warning growing more urgent.

“There are multiple victims, multiple locations, including James Smith Cree Nation and Weldon. Early indications may be that victims are attacked randomly

“This is a rapidly unfolding situation. We urge the public to take appropriate precautions.”

After leaving Weldon, Myles’s movements remain largely unknown. A possible sighting placed him in Regina just hours after the murders, at 11:45 a.m., according to another emergency alert. An Interprovincial Emergency Alert went out for Alberta. Over the next four days, potential sightings of him streamed into the RCMP from Ontario to British Columbia.

In JSCN and nearby communities, people were terrified. Hotels kept their doors locked, asking guests to use the back doors. People peered outside from behind their curtains. It was a province on edge.

The dead were removed from JSCN and taken to morgues in Melfort, Prince Albert and Saskatoon because there were so many of them. The injured, too, were spread around the province.

An emergency alert issued by the RCMP at 11:39 a.m. the next day laid bare the monumental task ahead: There was no new information to share but the suspects were still at large. Their direction of travel was unknown.

That changed on Monday afternoon when the RCMP announced they’d found Damien Sanderson’s body. He had never left JSCN.

Damien was found in the north part of the reserve, in a heavily grassed area near Chakastaypasin Band Chief Calvin Sanderson’s house,

Chief Calvin says he’d spotted some concerning signs of someone being injured nearby — blood on a fence post and on the gravel, a bloodied T-shirt — and reported it to the RCMP.

“I didn’t realize that Damien was lying nearby all night,” he says.

“He must’ve sustained his injuries and then come to my house to get help. But I was at home in the trailer and had the AC on. It’s pretty loud, so you can’t hear anything.”

Damien’s injuries did not appear to have been self-inflicted. It is still not clear how he died. Skye believes her husband was murdered by his brother after he tried to stop him from killing Martin. Similar ruminations have been floated around the community.

The RCMP seems to be following a similar line of inquiry.

“We may never know how that incident unfolded between the two of them,” RCMP Assistant Commissioner Rhonda Blackmore later told the media.

Skye had to drive to Saskatoon to identify her husband’s body. She was on her way when her 10-year-old son discovered via TikTok that his father had died. He was distraught.

“Maybe the media is putting s–t in his head like his Dad was a monster, but I’m trying to tell him his dad was not like that. But he’s badly confused.”

In the end, Skye walked out of the funeral home before identifying Damien. She was angry he’d been taken to Saskatoon like they were trying to hide him away, when he didn’t even live there. Skye’s mother identified his body instead, and after laying eyes on him, told Skye she shouldn’t see him. He had deep slashes across his chest, his hair was falling out and his skin was dark.

In Cree tradition, caskets are supposed to be open. Given the condition of Damien’s body, the family would not be able to comply with that ritual.

Skye worried that no one would show up at Damien’s funeral, given the circumstances. But 1,900 people did. Even now, people choose to believe that his brother forced him into being part of the murders.

The disruption caused by the manhunt complicated the community’s attempt to mourn. On Tuesday at 11:40 a.m., the RCMP announced a possible Myles sighting at JSCN. Police cars streaked across the countryside and headed back to the scene of the crimes. Armoured vehicles and ambulances poured into the reserve. A police helicopter hovered overhead. Members either shut themselves indoors or drove around the boundary, telling people to be careful.

Three hours later, police resources began trickling back out of the community. The sighting had been false.

Another day with no information passed. But on Wednesday, everything changed.

Shortly after 2 p.m., Wakaw RCMP received a 911 report of a break-and-enter in progress. Myles Sanderson was said to have been standing outside a residence northeast of Wakaw, armed with a knife.

Myles had broken into a woman’s home and held her at knifepoint, demanding she hand over the keys to her white Chevrolet Avalanche, according to several accounts. The woman did so, pleading for her life. She declined to be interviewed because she was too traumatized by the experience.

An account from a neighbour named Richard Orenchuk was later posted on Facebook. Upon hearing about the robbery, Richard called his wife, Shawna, who was coming home from work and saw the truck heading north at between 130 and 140 km/h. Shawna called the RCMP and followed Myles but couldn’t keep up on the gravel roads.

Between 2:49 p.m. and 3:35 p.m., the Saskatchewan RCMP operations communication centre received more than 20 reports of sightings of Myles.

Shortly after 3 p.m., One Arrow First Nation chief Tricia Sutherland alerted her community, located 60 kilometres west of where the Chevrolet was stolen, of a sighting of Myles on the territory and ordered a full lockdown. Sutherland would not speak about why Myles was in the community, but JSCN members say he had family there.

Myles didn’t stay in the One Arrow First Nation long. At about 3:30 p.m., he drove past an unmarked RCMP cruiser at 150 km/h and a police pursuit began. Police cruisers shunted his car off the road and into a ditch shortly after 3:30 p.m. He was apprehended and taken into custody but later went into “medical distress” and died upon arrival at Saskatoon Hospital. Sources have since told Global News that Myles died by ingesting pills shortly before his arrest.

“This evening, our province is breathing a collective sigh of relief,” RCMP Assistant Commissioner Rhonda Blackmore said later that night during a media conference.

But that relief didn’t extend to investigators. Myles’s cause of death remains unknown. So does his motive. So do his whereabouts for the four days he was at large.

On Sept. 9, the black Nissan Rogue Myles was travelling in when he first fled JSCN was found in a thicket just off a gravel road, five kilometres east of Crystal Springs — just 60 kilometres south of JSCN.

The area is sparsely populated, with only fields and one or two houses for miles in every direction. The Rogue was dumped beside an abandoned house, barely concealed by the trees it was left beside.

It seems unlikely that Myles would have driven 300 kilometres south to Regina, only to return and dump his getaway car so close to the crime scene. The RCMP did not answer questions when asked if they had ruled this sighting out.

Farmers in the area say they didn’t see him while he was on the run. But they say that doesn’t mean he wasn’t around — there are plenty of places to hide.

“I did start carrying a gun when I heard he was in the area,” one farmer said.

The home Myles broke into on Sept. 7 and stole the Chevy Avalanche from is a rural property near Wakaw and Yellow Creek, 12 kilometres south of where the Nissan Rogue was dumped. We traced the journey between the two points. It’s one long gravel road until you reach Highway 41, and there is little sign of life among the endless wheat fields.

Wakaw residents say there were sightings of Myles walking along the highway in the days prior.

It’s unclear if they are legitimate. A lot of things remain unclear.

“Without him being alive at this point in time, some pieces of that may not be able to be pieced together,” Blackmore said on Sept. 7.

“His motivation may at this time, and forever, may only be known to Myles.”

Myles’s death brought both relief and anger to JSCN. Some were glad the “monster” was gone. Others believe he should have lived long enough to face repercussions.

Without him, there will be no public criminal trial. No statements read to him of the pain he wrought, him sitting in a dock. On Wednesday, two public inquiries were announced to take place into the deaths by the Saskatchewan coroner’s office, but it is of little solace. There is no closure.

JSCN Chief Wally Burns labelled his death “cowardly.” Many concur.

As the sacred fires were lit and the funerals began, JSCN members tried to refocus their attention on healing. A large cross was erected for Earl Burns, near where his bus was found, his cap placed atop it.

People poured in from across the country. Cars with licence plates from as far afield as New Brunswick and Ontario overran the once-quiet gravel roads, as people travel from service to service, paying tribute to victim after victim.

People brought food, money, fuel cards. Community fish fries were held at the school — with hundreds of kilograms of fish brought in from 500 kilometres away, at Reindeer Lake.

Mourners pointed to the sky as eagles circled overhead, watching over ceremonies. Eulogies preached forgiveness to the Sanderson brothers, despite what they’d done.

Concerned that Damien’s role in the spree would stigmatize Skye, one of the victims’ brothers, Darryl Burns, brought her back into the community fold in a moving moment. At a press conference four days after the attacks, Darryl gathered Skye into his arms during his speech and told his audience that he was there to forgive her.

Skye, who had been slumped in a seat for most of the event, her face fixed in a vacant stare, started sobbing, and howled: “I lost my husband and my Dad too.”

But amid the sombre moments, laughter abounded across the community. Jokes were shared. Wakes and communion ceremonies were for singing and feasting. At Gloria’s funeral, Chief Burns recalled her introducing herself to him as a “queen” and wondered how that was going to go in heaven with the recent passing of Queen Elizabeth.

Fish fries were for reminiscing and sharing memories of the dead. Spirits were kept high. But many fret about what happens after the funerals end, when the visitors leave, their houses are empty and the headlines fade. How would they keep their spirits up then?

One victim still remains in hospital, while 16 have been discharged. Creedon DiPaolo was released with “lots of nasty scars” about a week ago. His mother, Arlene, was released on Thursday. He says she is still “shaken up” and doesn’t want to return to JSCN.

Creedon went back, albeit briefly, to pick up some clothes.

“It seemed totally different. It didn’t seem like home anymore.”

Creedon says he will return at some point, but for now, he is not ready. It still pains him to discuss the stabbing. His two-year-old daughter, who was home at the time of the attacks, is afraid every time she hears a knock at the door, asking if “that guy is coming back.”

The healing has begun, but the road will be long. The issues of mental health support and ongoing trauma loom large. Chief Burns has asked Ottawa for ongoing support in these areas. On Friday, he was in Toronto for the National Summit on Indigenous Mental Wellness, which brought together Indigenous and federal leaders from across Canada. The stabbings were a central focus.

“Yesterday was the start of a new tomorrow for our nation,” Chief Burns told Global News afterwards.

As well as working on their support requests, JSCN leadership will now work with the Department of Justice to ensure communities are informed of the release of dangerous offenders, he says.

Chief Burns was supposed to stay in Toronto until Monday. But he flew back after just 24 hours because he didn’t feel comfortable being away from his community that long.

“We have to lay down the foundation for our healing,” he says.

For Skye, she simply wants an apology. She says the RCMP should have done more to stop Damien and Myles the day before the attacks. She wants her husband to be counted among the victims.

She moved house for a fresh start but admits she’s still struggling. She believes many people helped Myles escape, and she is scared they will come after her. She worries for her son, who still thinks his Daddy is coming home. She doesn’t want to raise three children alone.

“Maybe they should’ve murdered me, and then my husband or my Dad, and all those people wouldn’t be dead,” she says through tears.

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.