By

Simon Little

Global News

Published June 14, 2022

15 min read

After a B.C. First Nation revealed that 215 suspected unmarked graves had been located on the grounds of the former residential school in Kamloops, the world paid closer attention to the cruel system of assimilation and abuse Indigenous Peoples have endured in Canada.

This is Part 1 of a three-part series examining the connection between residential schools in B.C., what is known as the ’60s Scoop and efforts to reform what’s been described as a ‘broken’ system of Indigenous child welfare.

Every time Marylou Fonda goes to the doctor’s office, she’s confronted with a question she can’t answer: are there health risks in your family history?

“I don’t have a history of anything. My history starts with me,” the Fort St. James, B.C., resident told Global News.

“Sometimes it’s downright traumatizing when you’re in a doctor’s office…. You have to say ‘no’ because you don’t know.”

Fonda is one of thousands of Indigenous people taken from their birth families, usually without consent, and placed in non-Indigenous homes in what’s now known as the ‘60s Scoop.

The term refers to a period between the 1950s and 1980s, after amendments to the Indian Act let provinces take over Indigenous child welfare. The children were stripped of their language and culture, and left with complex questions about their identity. Many faced physical and sexual abuse.

An $875-million settlement with the federal government has accepted claims from more than 20,000 survivors, but advocates say the true number is far higher.

Amid the national reckoning over suspected unmarked graves at residential schools across Canada, ’60s Scoop survivors in British Columbia are sharing their stories — and calling for more government action.

Katherine Legrange, a survivor and director of Sixties Scoop Legacy Canada, is leading the call for a national inquiry that she says would document the true scope and impact of the scoop. She’s also seeking provincial funding for an inaugural regional gathering for B.C. survivors to tell their stories and provide mutual support — an initiative backed by the Songhees Nation, where she serves as executive director.

“There really hasn’t been that study to look at those long-term effects of permanent child removal, where folks ended up, reunification and repatriation services that still need to be put into place — and folks who have been affected are still calling for healing resources,” she explained.

“Survivors have really expressed the need to share their stories and to connect with other survivors across the nation, so for us, it’s really, really important to be able to share our experience and have that validated.”

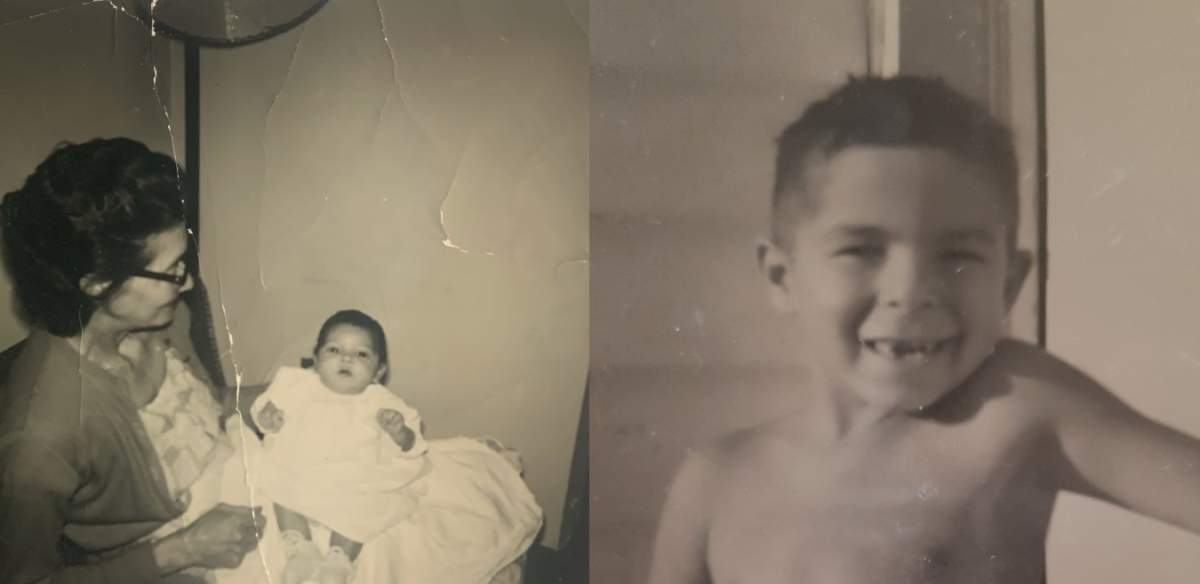

Fonda was taken from her mother, a woman of the Moravian of the Thames band near London, Ont., as an infant in 1963. She spent six months in foster care before being adopted by a white family who later moved to Fort St. James.

“I was told I was chosen,” she said. “It made me feel good … and also I used that when kids would be mean.”

Fonda’s parents told her she was from Ontario’s Six Nations reserve, but beyond that, she said, she had little connection to her First Nations culture.

“Mom never said you can’t learn about it or you shouldn’t learn about it, but I don’t know if they really knew how to help us do that,” she said.

At school, Fonda faced racism from non-Indigenous students, who called her names like “wagon-burner,” but she said she was also an outsider with First Nations students.

“The Indian girls were kind of like, ‘Oh, well, you know, you’re not one of us. She’s white, she looks white, but she’s not white,’ and so yeah, the name-calling … it was brutal.”

Fonda said she grew up loved, but because her adoption records were closed, she’s been left with a huge gap in her medical knowledge — and questions about the circumstances of her birth and adoption that may never be answered.

It wasn’t until 2016, after a grandson came to live with her, that she decided to open the “can of worms” of researching her lineage and apply for Indian status — a process that took nearly three years.

“I always kind of wanted to find out about things, but I think you just have to be ready in your mind, in your body and your soul, to actually make that step,” she said. “Is it going to be good or is it going to be bad? So it’s kind of scary.”

Finally, a letter came confirming her status and the band she belonged to.

“It was a very, very surreal moment to find out that’s where you came from and this is where you belong,” she said.

Some of the moments that followed, however, were not what she expected.

When Fonda called the band office looking for help tracing her lineage, she was told they were too busy and to call back another month. She never did.

“It made me feel like, do I even want to have anything to do with you people?” she said.

Fonda didn’t give up. Armed with her birth name and band, she began searching Facebook and identified two people she thought might be relatives. Taking a “huge leap of faith,” she reached out, and several months later, a man she believes to be her uncle responded, pledging to help any way he could.

The man sent her an old photo of a log house taken in 1909.

“He said, ‘Well, your grandmother, your grandfather, they’re probably in this picture right here.’ And I was like, ‘Whoa, really?’ It was just so, so amazing. It was it’s kind of like, ‘Oh, here’s people.’ Like it’s a part of my history.”

Further digging revealed a 2018 obituary for the woman Fonda now believes was her mother, but few answers about her mom’s life or the circumstances of her birth.

“I won’t ever meet my birth mother, and that’s on me, I guess. I just left it too long. But who knows? Like, who knew, right? I didn’t know,” she said through tears.

“I did get an answer … (but) the connection that I was kind of hoping for was a female … you know, women talk around the kitchen table … I thought maybe the aunties might have some answers for me that an uncle who’s the same age as me wouldn’t.”

Today, Fonda sits on the Indigenous committee with her union and has participated in projects supporting the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls movement.

Her family connection in Ontario recently invited her to her first powwow in September, which she’s planning to attend with her daughter.

“To me that is so special, to be able to go to the place where I guess I should have been from all along and to just take it all in…. It’s going to be very emotional, very exciting and kind of scary,” Fonda said.

“Being adopted has been very, it’s a personal thing to me…. You have to have a safe space to just share your story and share your feelings.”

Bruce Nichol was born in North Vancouver in 1959 to a Haida mother and adopted by a non-Indigenous family in Lynn Valley in North Vancouver nine days later. Growing up, he said he was told he was “lucky” not to have been raised by “those people.”

“I remember telling people when I would experience racism as a little kid, ‘Oh, no, I’m not like that, I’m white, I’m in a white family. My dad owns a business,’” he said. “It’s a balancing act because I loved my youth, but it’s not one that I was born to have.”

Other family members have since told him they would have taken him in at birth, had it been a possibility.

“I would have experienced my native life I was supposed to have,” he said. “Now I am who I am.”

Nichol described himself as a happy and outgoing youth, but said he encountered frequent racism, like being called a “half-breed” by an opposing soccer coach — experiences he said it took him a long time to come to terms with.

But he said he didn’t fit in the Indigenous world either; the first time he visited a reserve as a 13-year-old he was beaten up.

“Probably the first three times I went to a (reserve) I had not a welcoming that I expected because, hey, I’m half Haida, and I thought that was going to be my in,” he said. “Well, I showed up thinking like a white guy, like who is better than all these guys.”

After obtaining his Indian status at age 25, Nichol was able to track down his mother, who he learned was only a few kilometres away from where he lived at the time.

His biological father, he later learned, had been his mother’s caregiver who had sexually abused her as a teen. After Nichol was born, his mother was sterilized.

“The meeting was not Hollywood because as I said earlier, she had a caregiver impose himself upon her,” he said.

“When I met her, she opened the door and I looked like him, so she was not, ‘Oh, I’ve been waiting for this moment all my life.’ It was actually the opposite. It was a very sad situation and I felt huge compassion for her.”

Nichols said it was years before his mother was comfortable being called “mom.”

The two had eight years together before alcohol took her life, but during that time, he was able to meet an aunt and cousins, who he remains close with.

Nichol first visited Haida Gwaii for work in his 30s, where he made some family connections, but also felt a sense of dislocation.

“I figured, hey, there’s a Haida boy coming home. You know, I was expecting a, you know, not a parade, but, you know, maybe some kind of gathering and acknowledgment (but there was) nothing.”

It wasn’t until he became a father himself that Nichol found a connection with First Nations culture through the All Native Soccer Tournament, where he coached his sons.

Other parents were wary of him as an outsider at first, he said, but over time he built friendships and connections. He became an “uncle” to the players, he said, even though they still made fun of him for mispronouncing Indigenous names.

“We went to Denver for the North American Indigenous Games and both my boys were on team B.C. and we had big success and so much fun,” he said.

“That really cemented that, hey, I’m a native — I like it.”

The 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples found that Indigenous children made up fewer than one per cent of kids in care in B.C. in 1951, but that by the mid-1960s the number had climbed to more than 34 per cent. Some communities were hit particularly hard — the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs estimates that between 1951 and 1979, more than two-thirds of children from Spallumcheen First Nation were apprehended by provincial social workers.

But exactly how many children were taken in B.C. and Canada during the ’60s Scoop, and where they were sent, remains unclear.

Documenting the dispersal of children has fallen to grassroots groups like the Sixties Scoop Network, which has tried to map where Indigenous kids were “trafficked” as far away as Denmark and New Zealand, said co-founder Colleen Cardinal.

In August 2021, Sixties Scoop Legacy launched a call for a national inquiry, a campaign backed by numerous national and regional Indigenous groups and former senator and chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Murray Sinclair.

The settlement’s estimate that 20,000 children were taken can’t be accurate, said Legrange, because Métis and non-status Indigenous people were excluded from it.

“There’s more than we even know. I think that some of the records are not accurate, some of them are missing and some of them were just flat-out destroyed as part of that systemic racism,” she said.

Legrange said an inquiry would get a clearer picture of who was affected by the scoop, and touch on the intergenerational connection between residential schools, the ’60s Scoop and the “Millennium Scoop,” a name given to the ongoing apprehension of Indigenous youth who remain heavily overrepresented in the child welfare system.

Those connections were not explored in Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2015 report, she explained.

“It’s important to collect testimonials of survivors with lived experience through the ’60s Scoop, but certainly from our children and our grandchildren who have been affected intergenerationally with that trauma of permanent child removal,” Legrange said.

“We need to let our parents and grandparents know that this was not their fault, that our permanent removal was often a result of systemic racism.”

An inquiry would also highlight the lack of services available to survivors. While the 2018 settlement awarded them $25,000 each, it left the creation and delivery of services in the hands of the Sixties Scoop Healing Foundation, which has only just begun its work with a $50-million trust.

Executive director Jackie Maurice said the foundation gave out its first eight grants last fall with plans for two more disbursements this year. The money can be used in different ways, from counselling and health services for survivors to staging healing gatherings, she said.

“We’re just beginning to create a foundation for the healing foundation because we are brand new,” she said. “When these various organizations across the nation are applying for grants, that it’s a specific community that can decide what they need as it relates to directly serving survivors, it will be different across the nation.”

But Legrange said major gaps remain, particularly around helping individual survivors — including those sent overseas — with repatriation, reunification, language and culture.

“There’s still families that have never reconnected kids that don’t know their birth families or communities, kids who were lied to, told that they were different cultures or ethnicities to hide their past,” she said.

A final, key element of an inquiry, she said, would be a set of strong recommendations aimed at keeping Indigenous children in their communities and breaking “the cycle of systemic racism” that continues to bring so many Indigenous children into care.

In response to the inquiry call, an Indigenous Services Canada spokesperson pointed to the Sixties Scoop Foundation’s endowment’s “forward-looking funding to support healing, wellness, education, language and commemoration.”

“The Government of Canada remains committed to righting the wrongs of the past and bringing a meaningful resolution to this dark and terrible chapter of Canada’s history, and is open to considering all means of supporting Indigenous Peoples as they seek closure and restorative justice,” wrote Megan MacLean by email.

Ottawa remains committed to resolving claims, including those of Métis and non-status people not covered by the settlement, outside of court where possible, it added.

In the meantime, survivors wait, but Nichol said many of them can’t wait much longer.

“It’s got to be done soon because we’re old and people are going to die — and we are, we have people dropping off all the time for suicide, poor health,” he said.

“We’re invisible because we’re lost. The native culture is in the reservation world and in each nation, it exists…. We’re out there floating by ourselves and it’s a travesty.”

Earlier this year Fonda, Legrange and other survivors met with B.C.’s ministers of children and family development and Indigenous relations and reconciliation about securing funding for a regional healing gathering.

Fonda has also filed a grant application with the Sixties Scoop Healing Foundation in its latest funding round.

“We hope to create a safe space so that people feel like they can share, but share as much as they’re comfortable sharing. And some people might not be able to share anything and that’s OK,” Fonda said.

Colleen Cardinal, a ‘60s Scoop survivor and advocate who has organized four national healing gatherings, said such events are important for survivors who may not have an easy time reconnecting with their communities of origin or their culture.

Some return to find families still grappling with the trauma of their children’s apprehension or their own residential school experience, while others find themselves viewed as outsiders.

“It’s hard to explain to somebody who hasn’t been through that, who hasn’t been brainwashed like that because you don’t feel like you fit in with your native family, but you don’t really fit in with your white family and you don’t feel like you fit in anywhere,” she said.

“If you don’t have access to folks who carry ceremony or if you don’t know who to talk to, it can be challenging because you have this barrier where you don’t feel like you can ask anybody.”

Cardinal described her events as akin to a “sleepaway camp,” with workshops addressing culture and trauma during the day, and more lighthearted activities in the evening.

Participants start from “zero” she said, and are introduced slowly to things like sweat ceremonies or how to smudge.

“Those people come there strangers and they leave in tears. And there’s a lot of them are still lifelong friends and they’ve supported each other,” she said.

For Legrange, a regional gathering would also be a chance to map out survivors’ needs and challenges in British Columbia, like barriers to reclaiming their birth names or accessing adoption records.

She said she’s hoping for initial funding to hold the first gathering, followed by longer-term support to permit gatherings in different parts of the province.

B.C. Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Murray Rankin declined multiple request for an interview for this story. The ministry did not return a response to questions about funding for a regional gathering by deadline.

Fonda hopes to see regional gatherings eventually held around the province for survivors.

“Even to hold a drum in their hand and drum, or hear the beat of the drum like your heartbeat or attend a blanket ceremony, have people singing in native tongue — that’s a huge, huge thing,” she said.

“I didn’t grow up with that. None of us did. We didn’t have culture; anything I’ve learned I’ve had to go out and reach for that.”

Comments