In a sparse hospital room in the eastern Ukrainian city of Dnipro, 42-year-old Oleh runs a thick piece of metal over in his hands, considering its size and weight.

The piece of shrapnel, about five centimetres long and one centimetre thick, was embedded into his right shoulder. The Ukrainian soldier still marvels at the fact he survived the blast.

But while he counts himself lucky, in other ways, he says he is not.

When he considers the fact that he is here on a hospital bed recovering, while his comrades remain out on the front lines fighting the Russians, he finds it unbearable. He pauses and takes a long, drawn-out breath, staring intently at the fragment between his fingers, before covering his face with both hands and breaking down.

“I’m sorry. I did not expect such a reaction from myself,” Oleh says after a few minutes, having pulled himself together.

“It’s because the guys from my unit, many are young and not very experienced, and because I was with them when I was evacuated here. My thoughts were always with them, with those who remained.”

Oleh, whose last name we cannot use, was rushed to the hospital one week ago — the piece of shrapnel he has kept as a talisman responsible for the gaping hole in his right shoulder.

The Dnipro resident is the chief sergeant of his battalion and was driving with another soldier when their car came under fire. He says an explosion behind the vehicle blew out their windows and sent fragments of metal flying inside.

The soldier he was travelling with was not wounded, he says, and the man healed the wound in his shoulder as the shelling continued around them. The soldier was pressing so tightly on Oleh’s wound, that the heat from the shrapnel burnt his hand.

He says he was stitched up and stabilized at a field hospital by an American medic from Kansas, before being transported to Dnipro.

His first thoughts, however, were not to inform his wife and two sons who are currently in Warsaw, Poland, of his injury, but to check on his soldiers.

Dnipro serves as wartime hub

The closest city to the front lines of the war in Ukraine’s southeast, Dnipro has become a hub for war efforts — both humanitarian and military. The bustling city of about one million residents is Ukraine’s fourth largest, and has remained a relatively safe island as war rages along a 480-kilometre front line just several hundred kilometres away.

Get breaking National news

Accurate estimations of casualties suffered by the Ukrainian military are hard to come by.

About one month ago, Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelenskyy told CNN that about 2,500 to 3,000 Ukrainian troops had been killed and 10,000 had been injured. Russia claims the casualties are much higher.

Even estimations are tightly guarded information. During our visit to the hospital, Global News was restricted from asking any questions about civilian casualties or deaths. We are also not permitted to identify where soldiers are fighting or the hospitals they are brought to, in case they are targeted by missile attacks.

There is one dedicated military hospital in Dnipro, while the others in the city are treating both civilians and military, such as the one Oleh was brought into.

Ahead of our visit, a hospital representative meets us outside. She says many of the soldiers currently being treated aren’t willing to talk to the media just yet. She’s found just two who will speak.

We’re led into the Soviet-style hospital via the main entrance and up a concrete staircase, into a wing painted a light shade of pink. The wide hallway is devoid of people, other than three doctors — two female and one male — lingering by the first doorway. Inside, two injured Ukrainian soldiers sit on their beds chatting to one another.

The doctors will only answer very general questions and say nothing even in reference to the number of soldiers being treated here, nor how old they are. They say most of the injuries they see these days are similar to what the two men are being treated for — shrapnel wounds, primarily on people’s hands, legs, chest or stomach.

While they say they are well-stocked for most of their operational needs, they’re in need of metal rods used to reconnect bones. They say their patients, like Oleh, usually receive first aid at a field hospital before being transferred into the city.

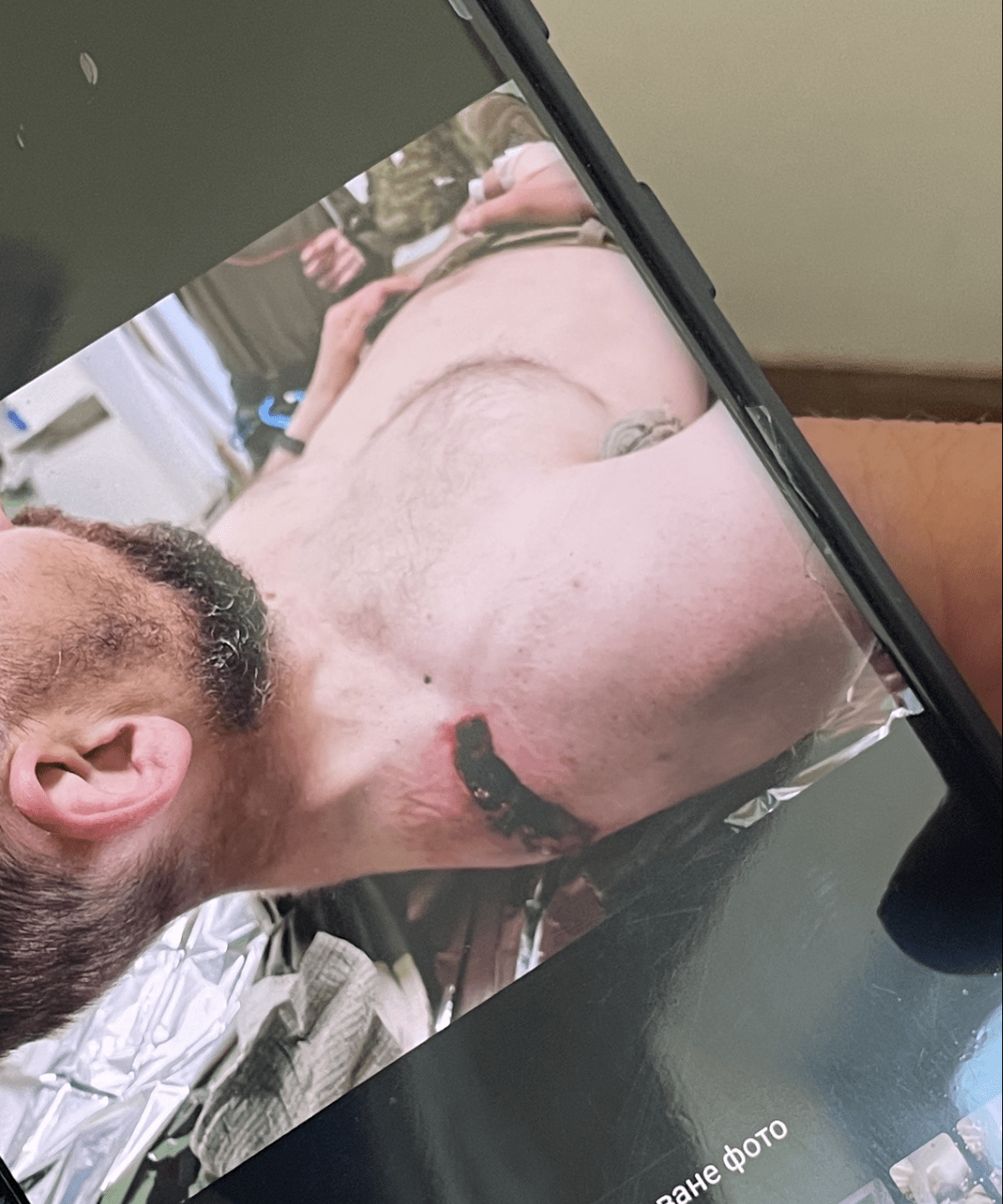

Oleh is sitting on his bed shirtless when we arrive to see him, his right shoulder covered in a large, white bandage. The room is nothing more than two single cots and two small tables between them. Another injured soldier, Yevgen, reclines on the opposite cot.

- Bodies found in area in Mexico where search is on for 10 missing workers from Canadian mine

- Israel team, JD Vance booed at Olympics opening ceremony

- Latest alleged Iranian regime official found in Canada wants his identity hidden

- Trump takes down racist AI video of Barack and Michelle Obama as monkeys

The table is stocked with bottles of water and dishes left over from lunch. Yevgen waves us in.

While the soldiers say they’re open to being filmed, hospital protocol dictates that faces must be blurred.

The three doctors and the hospital representative linger in the back of the room.

‘There are much worse casualties among us’

For Oleh, this war is nothing new. He volunteered with the Ukrainian Armed Forces when the war began in the Donbas and then returned to civilian life as an entrepreneur, before returning to live combat once more when the full-scale Russian invasion began in February.

“In comparison with 2014/2015, all this is much more difficult. The density of artillery fire, aircraft, helicopters, everything is much more complicated,” he says.

“There are many more casualties among us — wounded and killed. And it is very difficult, but as my brother told me, we are fighting for our freedom. We are fighting for our country, for our future.”

But their fight is not only happening on the ground, Oleh says. He says his men are in desperate need of humanitarian, medical and military aid. He is grateful that there are donations in the first place, but says they are often slow to make it into their hands. But it isn’t only weapons they are lacking.

“The war takes place not only with ammunition and weapons, the war takes place on different fronts — on the cultural fronts and information fronts, as well as the ideological front. And we need support for all of it,” he says.

“We are fighting for freedom, for our own, both for Ukraine and for the whole free world.”

‘Russia is the enemy’

Oleh’s 52-year-old roommate Yevgen, from Western Ukraine, was brought in about three days ago, after sustaining a similar injury on the front line. He was driving with four other soldiers when the shelling began. Yevgen received a shrapnel injury to his hip, which he says went bone-deep, but was the only one injured.

“Thank God that it was only me, and all others were alive and well. Thank God we continue to serve. I was lucky,” he says.

He has crutches propped up beside his table and struggles to move without wincing.

However, both men are desperate to recover as soon as possible so they can return to active service. They each say they will be home only long enough for them to get the clearance to return to the front again.

The most animated they both seem is when asked if they have any message for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Yevgen scoffs, propping himself up in bed.

“The enemy has already shown his face, through what he has done to the civilian population. He did not come to release us. He came to plunder, defeat and destroy us as a nation,” he says emphatically.

Oleh agrees. He grabs a black t-shirt that was folded at the end of his bed and holds it in the air, saying he’d bought it a few years ago, because it was how he felt at the time. It says: “Russia – enemy.”

“Many people in Ukraine did not perceive Russia that way, and it is only now, after this large-scale offensive, that they finally understood this. This applies both in Ukraine and around the world… that who we are dealing with is the personification of evil and everything barbaric in the world. That is modern Russia.”

During our interview, an air raid siren sounds. Barely anyone notes it has happened. There is no running in the hallways or moving patients out of rooms. Everyone is used to it now. Oleh looks bemused that we have even noticed it.

After the hospital spokesperson informs us the interview is over, Oleh isn’t quite ready for us to go. He waves me over to look at his phone, to show off a photo of the blood-stained hole in his military uniform where the shrapnel ripped through it.

There’s a video of him in the back of an ambulance with two other men, periodically giving the thumbs up and smiling into the camera. There’s a photo of him being seen in the field hospital, by the American nurse from Kansas. There’s a picture of him on the operating table, a close-up on the deep, bloody gash in his shoulder. There’s a photo of him and a cat. It’s not his.

“Ukraine will win this war, it’s only a question of the price it will cost,” he says.

“For less Ukrainians to die, we need more support. And better support. And we will win.”

Comments