The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is once again showing off its optical brilliance — this time, as it enters the home stretch of testing, it’s capturing stunning new images of a neighbouring satellite galaxy.

The JWST beamed back its latest round of test pictures, and when compared to images taken by NASA’s previous infrared observatory, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the results are astonishing.

The photos show the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy near the larger Milky Way, and when compared to Spitzer’s photos the new test images reveal unprecedented details of interstellar gas between the stars.

Each of the 18 mirror segments on the new telescope is bigger than the single one on Spitzer.

“It’s not until you actually see the kind of image that it delivers that you really internalize and go ‘wow!’” University of Arizona’s Marcia Rieke, chief scientist for Webb’s near-infrared camera, told a press conference Monday. “Just think of what we’re going to learn.”

The JWST is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has not only provided stunning images but has also been vital in providing scientific knowledge about our universe and its origins.

The $10-billion JWST has a much larger primary mirror than Hubble (2.7 times larger in diameter, or about six times larger in area), giving it more light-gathering power and greatly improved sensitivity than Hubble.

Get breaking National news

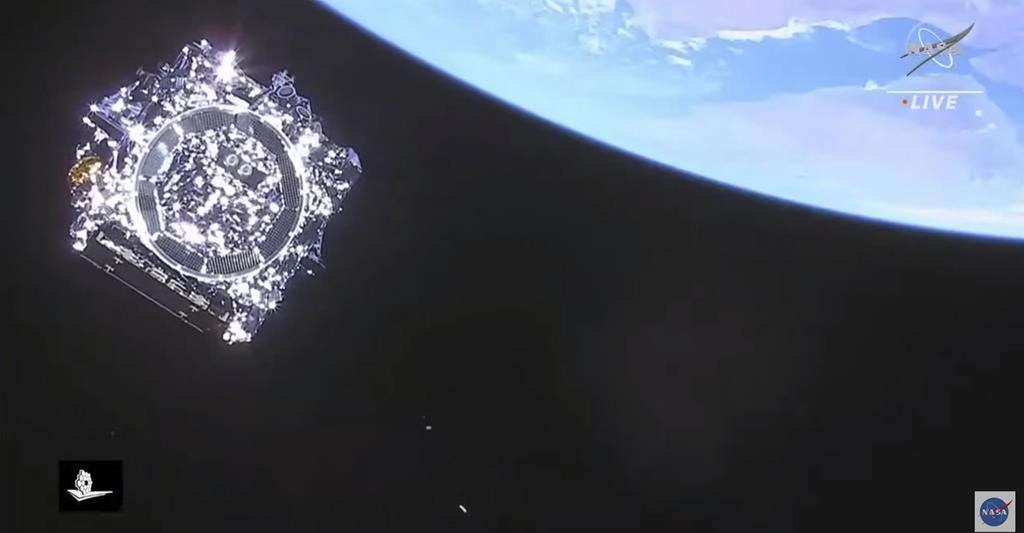

The telescope was launched into space on Christmas Day last year, and teams held their breath as there were worries the unfurling of its many parts might not go to plan.

The JWST launched, and there were no second chances — its extremely distant location in the solar system makes it impossible for human crews to work on it.

But the telescope’s massive sun shield, with 107 restraints holding it in place, was released correctly and everything has been smoothing sailing, so far.

Last month, the Webb sent back a first round of astonishing images of the Large Magellanic Cloud.

The sharply focused images showed a dense field of hundreds of thousands of stars rendered by each of the JWST’s science instruments.

At the time, the Webb team confirmed the telescope is now fully aligned and will become fully operational in July. However, scientists are keeping the identity of Webb’s first official target a secret, for now.

Once fully operational, scientists believe the telescope will be able to peer back in time, possibly to 100 million years after the Big Bang. And not only do scientists think they can look back into galaxies from that time, but they also think they might be able to determine the composition of those galaxies.

“Astronomy is not going to be the same again once we see what (Webb) can do with these first observations,” said Christopher Evans, Webb project scientist at the European Space Agency, said during the news conference on Monday.

— With files from the Associated Press

Comments