James Wood was laid to rest this weekend, marking more than three months since his body was found and five months since he disappeared from his home.

For some of his friends and family, it was a moment of closure for a life that ended with too many questions.

“We will never know how he died,” his sister Aleesha Wood said Sunday.

“We couldn’t have an autopsy because his remains were found two months after he went missing. His cause of death is classified as undetermined.”

For Aleesha, however, closure didn’t come with Saturday’s service, and it won’t come with the answer to those lingering questions. It’s somewhere in the offing and tied to changes to the way missing person’s cases are addressed that she believes could have made all the difference to her brother.

“I hope my brother’s death wasn’t for nothing,” she said. “Dealing with a loved one going missing was a nightmare, there’s not a lot of support … I don’t want anyone else to have to go through this.”

James’s mental health was an ongoing and well-documented issue. When he left his home last November, he’d already gone missing months earlier and suffered an assault that added to his struggles.

He was suspected to have schizophrenia, though a diagnosis had yet to be made, Aleesha said.

In the last two months of his life, Aleesha said James had been to the emergency room at least once a week to address pains that were never identified and were possibly a reflection of his mental state, more than his physical one.

Near the end of his life, he’d lost the ability to feed himself and had stopped drinking water. His hair was matted, and he’d stopped bathing.

His family kept telling everyone they could think of that he wasn’t OK and needed help but Aleesha said he continually failed to meet the threshold for medical intervention.

Get daily National news

“They told me, ‘Sometimes the threads have to unravel more before we help,’” she said.

“But to me, there were no more threads left.”

On Nov. 8, during a Zoom call with mental health workers, whatever was keeping him tethered broke.

“He ended up going catatonic,” she said. “I don’t know if it was from schizophrenia or PTSD, but he did.”

In turn, he was told he’d be apprehended under the Mental Health Act by police and in what Aleesha believes was fear, he walked out of his home dressed only in his pajamas and, as is known now, died shortly thereafter.

“It’s not far from Peters Road in Westbank, to the top of the Smith Creek road,” she said. “It was an hour-long walk and he was found was only a minute and a half from the road.”

Aleesha and her sister plan to take the walk Tuesday.

- Free room and board? 60% of Canadian parents to offer it during post-secondary

- Trump keeps carveout under CUSMA in new 10 per cent global tariff

- Porter flight from Edmonton loses traction, slides off taxiway at Hamilton airport

- Coffee-hockey combo — or breakfast beers? — for bleary-eyed Olympic fans

“My sister wanted to do this to let James know he wasn’t alone and we will do the walk with him to where he laid to rest,” she said.

The path he travelled that night wasn’t hidden. It wouldn’t have been hard to find him had people searched right away but the missing person’s notification went out to the public a day after he left his house and search and rescue crews weren’t sent out for 48 hours after he disappeared.

Aleesha has learned since that there were three credible tips made about the sightings of her brother, but again, they didn’t come in soon enough to make a difference.

Three months after he went missing, in January, Kelowna RCMP said they’d received a report of human remains located by a group snowshoeing in the area of Smith Creek Road. The snowshoers had been assisting in an informal search to locate the missing man, who was reported to have been last seen in the area in early November. Criminality was not suspected.

So many things went wrong for her brother but there’s one area she thinks could have made the most change.

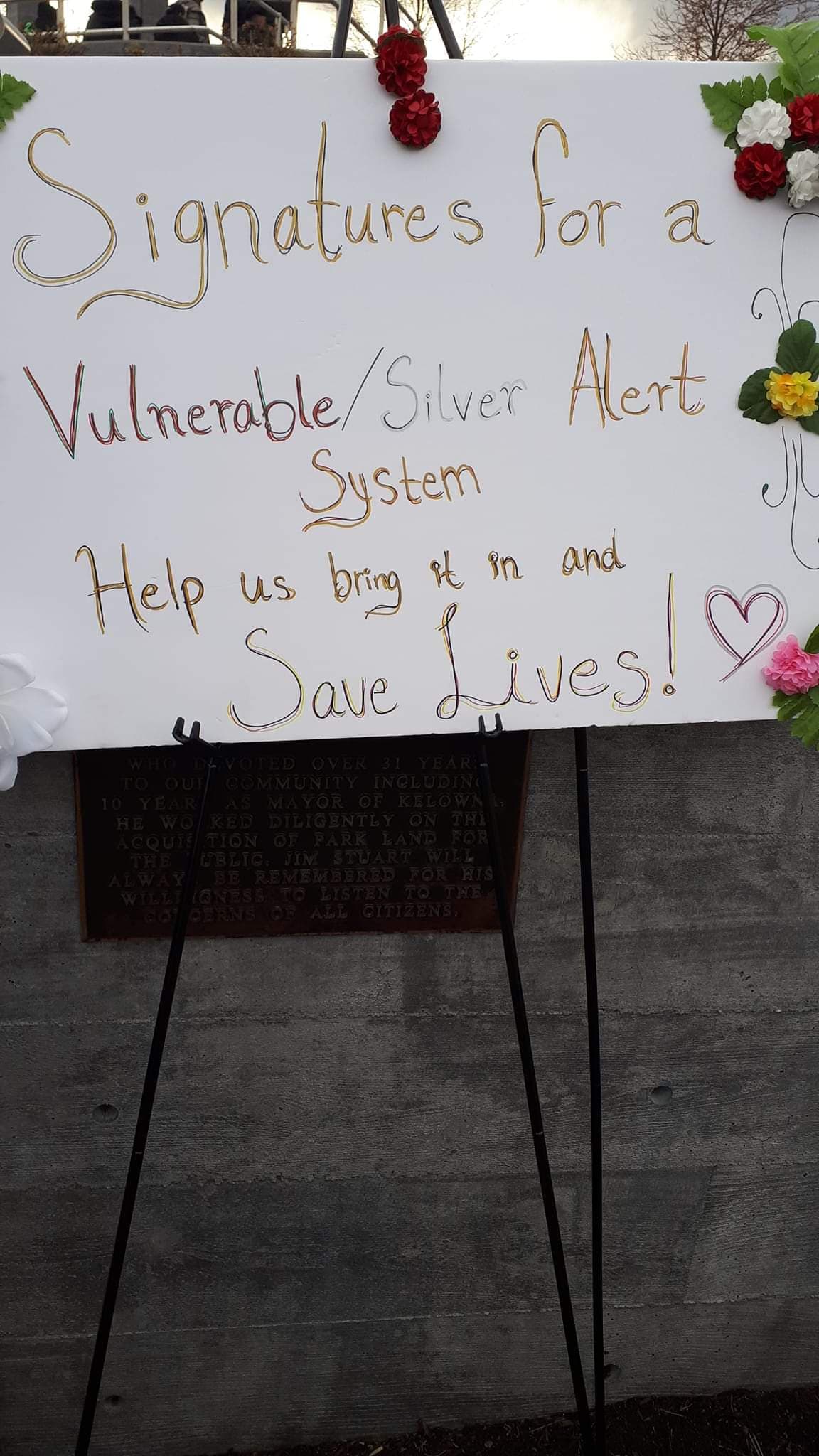

She’d like to see a Silver Alert System that is inclusive of all adults that have cognitive disabilities or mental health afflictions, not just seniors, to be instituted.

“An alert sent out to the Kelowna region could have saved his life, ” she said.

The couple who saw him that day wandering around would have heard he was missing and in trouble and would have alerted police to his movements early enough that he could have been saved.

“We could have saved him,” she stressed.

This weekend she and her family stood in Stuart Park and collected signatures for the Silver Alert implementation. She got around 100 there, and there’s another 1,100-plus on a Change.org petition. She’s also spoken to a local MLA who said he will bring it up with his colleagues.

She knows their support is largely symbolic but anything she can do to raise awareness, she said, is a step in the right direction.

It’s not an idea she came up with alone.

BCSilverAlert.ca already exists due to volunteers but she’d like to see it formalized and expanded.

Originally named for elderly, silver-haired missing people with various forms of dementia, the Silver Alert has been expanded to include other categories of vulnerable missing people. These include Alzheimer’s disease, which can affect people as young as 40 years old, dementia, and issues like brain injuries, autism and Down syndrome.

“People like this can vanish in an urban area and be very difficult to locate. They can perish, metres away from assistance. But because nobody knows they are lost, and they can’t ask for help, there is nobody to help them,” according to the website.

“The goal of the BC Silver Alert is to provide a valuable public alerting system so that specific, targeted alerts can assist first responders to locate missing people who meet the criteria for urgency and vulnerability.”

James would have met that demand for urgency and vulnerability.

“I am heartbroken over my brother and it shouldn’t have happened,” Aleesha said.

RCMP said that instituting such a plan would require a lot of work.

“The criteria to issue an Amber alert is a strict one, and one not often met,” Staff Sgt. Janelle Shoihet said in an emailed statement.

“To institute an alert system similar to that of the Amber Alert would require further discussion at the government and law enforcement levels.”

In B.C. alone she said RCMP receive over 25,000 missing persons report per year. Most of whom are located.

“Under the Provincial Policing Standards, police in BC, including the RCMP, are required to follow strict guidelines with respect to conducting missing persons investigations and those guidelines include risk assessments,” she said.

“Part of the assessment includes determining whether or not a media release should be issued related to the missing person. Once issued, the news release is automatically issued on our social media channels, our website and is, thanks to our media and community partners and followers amplified through their channels, allowing us to reach people locally, provincially, nationally and internationally. In this day and age of social media we have much greater capacity than we ever have to share such information.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.