Every time Abdullah Barez opens his Instagram and scrolls through his feed, he feels a sense of anxiety to improve his already-clean diet, or to go harder in the gym. Whatever he’s doing is just not enough.

“There’s this unrealistic expectation of having this six-pack, washboard abs and whatnot. Even a part of me wants it and social media kind of echoes me to have that,” he said.

Social media’s impact on how Barez feels about himself is not unique.

A 2020 study done by a researcher at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania found men who were exposed to muscular figures on Instagram immediately experienced “lower appearance satisfaction, weight satisfaction, and more social comparison compared to the neutral images.”

Barez admits to having been obsessed with how his body looked and while he has not been diagnosed, he thinks he checked off all the boxes for body dysmorphia.

Body dysmorphic disorder is a mental health problem that results in people having negative thoughts about their bodies and spending hours analyzing their bodies, trying to make improvements.

“The average man is comparing himself to a hyper-muscular, very lean body type and is going to make him feel worse about his own body because he does not live up to that ideal,” said Jennifer Mills, an associate professor of clinical psychology at York University said of the condition.

“That ideal could be incredibly unattainable for the average person, it requires a ton of time and discipline and access to exercise and nutrition that most men don’t have.”

If it’s abs, big arms or trying to get a wider back, hyper-focusing on certain body parts can be a common feature amongst men who try to achieve muscularity. Mills noted that the hyper-focus on specific body parts can lead to overexercising, major diet changes and potentially use of harmful substances or surgeries.

“Hyper-fixation could lead to really risky behaviours like steroid use because they feel like no matter what they do, their body isn’t good enough,” she said.

Some major red flags, according to Mills, include working out multiple times a day, significantly cutting calories or a willingness to seek out steroids. While social media does have a negative impact on men’s body image issues, she said, it’s hard to tell how much of a driver it is.

“If men are already vulnerable, then it’s going to make it worse for those folks,” Mills said.

Men’s body dysmorphia is not often centred around eating disorders or trying to look slim, according to Mills. She noted that changes to men’s caloric intakes aren’t drastic.

“We don’t see the same kind of extreme dieting behaviour necessarily that would qualify as an eating disorder,” she said.

Mills said that men with body dysmorphia often focus on achieving a certain level of muscularity. She noted they will convince themselves that going to the gym 2-3 times a day for several hours is necessary, begin to use unregulated supplements like anabolic steroids or consume an unhealthy amount of over-the-counter supplements like mass gainers, fat burners and creatine in hopes of achieving their goals.

The number of men suffering from body dysmorphia is pegged around 1-2%, but real number is likely significantly higher, according to Mills. The condition is not very well researched and that men would rather try to solve the problem than seek help, she said.

“It’s often under-diagnosed because men don’t necessarily seek treatment for this. If they’re dissatisfied with their bodies, they may be more likely to join a gym or to sign up for a supplement program or even riskier,” she said.

While body dysmorphia and image issues are mental health problems, Mills said they’re also social and health problems with far-reaching consequences.

“There may be other health consequences that are not even in the psychological realm, but injuries related to over-exercise that men may be experiencing or side effects from supplement use,” she said.

The 'negative role of social media images'

Participants of the Allegheny College study were split into multiple groups. Two groups of students were randomly assigned and shown a different set of photos. One group was shown muscular photos and the other a regular and more neutral Instagram feed. The results found the participants who saw muscular images of men “demonstrated a significant reduction in scores in appearance satisfaction compared to the group exposed to neutral images on Instagram.”

Get weekly health news

“The novel and interesting findings from this study provide preliminary evidence for the negative role of social media images, specifically via Instagram, on men’s body image and social comparison,” reads the study.

Authors of a similar study that analyzed 1,000 fitness-related Instagram posts for men wrote that the constant barrage of “perfect” male body types on Instagram photos “are potentially harmful to men’s body image, even if one considers that health-related messaging and physical activity promotion was prominent.”

Kyle Ganson, an assistant professor of social work at the University of Toronto, is currently studying eating disorders, muscle-building behaviours and body image. He said of the 20 people he’s interviewed so far, almost all have referenced certain Instagram influencers or YouTubers that are inspirations.

Through his research, Ganson has learned there is a large prevalence of men wanting to achieve what they view as the ideal body type — naturally or with the use of steroids and other performance-enhancers.

To Ganson, men’s perception of their body is a growing concern.

“I think they know that these sorts of (social media) platforms influence their body image and the desire to change their body in specific ways,” he said.

The negative effects of social media determining what the ideal male body looks like are not foreign to Barez.

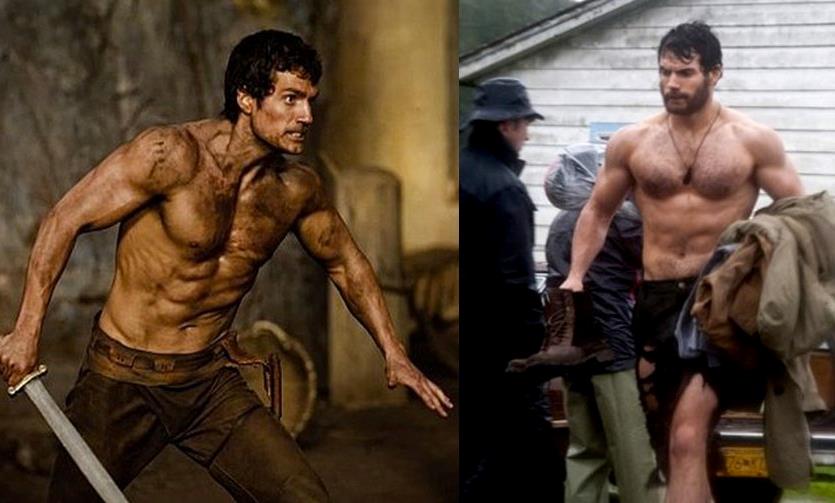

The avid superhero fan follows social media pages such as those of Henry Cavill, who played Superman, and Hugh Jackman, who played Wolverine.

“They present this insanely muscular, non-fat, unrealistic image … It’s made me have unrealistic expectations a little bit … that I don’t have enough muscle, I’m not big enough or not strong enough. It kind of feeds into that and slowly makes me think like that,” he said.

Barez, who regularly exercises and follows what he says is a good diet, said he’s coming closer to the point of accepting his body for what it is and not constantly focusing on where it should be.

“I can practically look at my body and say that I’m a healthy individual because I’m exercising and also eating right now, and I’m not starving myself,” he said.

Barez isn’t alone.

Sartaj Sandhu, who calls Surrey, B.C., home, said he’s been led to believe the perfect body is visible abs, big arms and toned legs and shoulders. Sandhu is aware of his body image issues and said that certain posts on social media still catch him off guard at times, leading him to make drastic changes to his eating habits and workout regime to achieve those goals.

“Even if it is not conscious, sometimes subconsciously, I am working on achieving that body, too, (telling myself), let’s go to the gym, dieting to achieve it,” he said.

Sandhu would often look at himself in the mirror during or after a workout and compare what he looked like to what he saw on his phone screen, constantly telling himself that he wasn’t good enough. That had him focusing less on having balanced and nutritious meals and more on starving himself, where he would not eat for days, so he could have a six-pack of abs and vascularity in his arms.

“We start comparing ourselves and if I do not get the same results … I feel I need to do more,” he said. “The thought process changes from ‘I need to exercise or work out for my health’ purpose to something more of a superficial image purpose.”

How Instagram fitness pages became addictive

The algorithm on social media, especially Instagram, uses collaborative filtering, where if someone spends a lot of time on the app looking at certain photos or accounts, they can get inundated with similar content, according to Jenna Drenten, an associate professor of marketing at Loyola University Chicago.

“If you start to look at some images of The Rock or Cristiano Ronaldo, Instagram will say you must spend a lot of time on this app. If you see these images, you must like them, so let’s show you more of this so that you can spend more time here,” she said.

The algorithm can send people down a rabbit hole, according to Drenten. She added that more people interacting with popular male athletes or muscular men’s photos help the app push that content more broadly too.

Instagram said it made changes to its algorithms in April 2021, noting that women were often being inundated with posts making them eat less and pushing a ‘skinnier’ body image. But even while it acknowledged the change, accounts promoting toxic eating habits were, according to CNN, able to circumvent the new policies and carry on posting content.

Creators on the platform need to be more cognizant of the content they’re creating and how it can affect people, Drenten said.

“Social media platforms like Instagram have a really powerful opportunity for consumers to change how we perceive ideal bodies and what we value as far as body image,” she said.

“The onus is on these platforms to understand from a more cultural perspective how these societal norms are shaped and then on consumers to be the ones to make the change in the content that we put out there.”

Whistleblower Frances Haugen, a former product manager at Facebook, whose parent company Meta owns Instagram, said internal studies from the company showed the app intensified eating disorders amongst young girls.

In a response to Global News, Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, said it has launched campaigns to help with negative body image and eating disorder issues.

The organization said they’ve “launched dedicated resources for Canadians coping with eating disorders and body dissatisfaction, based on the recommendation of experts” and creating “resources for people who may be affected by negative body image or disordered eating.”

They also launched a feature called the sensitive control feature which allows users greater control of the images they see by allowing them the ability to restrict and limit triggering posts and stories. A Meta spokesperson said they’re focused on creating a “supportive, healthy environment” and want to find the “right solutions to some of the most complicated issues we face” like eating disorders and body image.

Meta did not clarify if photos of muscular men, which can be triggering to some, would be covered by that feature.

How to navigate the pitfalls of Instagram-fuelled body dysmorphia

Instagram needs to take initiative to explain how their algorithm curates content to users and limiting what content could be triggering and undesirable, Ganson said.

If people had a higher level of transparency around the content they’re being fed, they could have greater control over what is coming into their feed and avoid being bombarded by certain images or videos, he said.

“I think the responsibility does lie on transparency, and ultimately being a private company they get to decide on how much you engage with certain posts,” said Ganson, who is skeptical that such a change will ever occur.

Abdullah Barez said that it’s taken years for him to get comfortable with his own body. Barez agreed with Ganson that Instagram is unlikely to make wholesale changes, especially to its algorithm. A Meta spokesperson pointed again to their newly-launched sensitive control feature noting that people have greater control over what they view, but Barez thinks that men will likely just have to “learn to live with it,” and that the changes still have gaps.

“We should have warning signs regarding that it’s not necessarily realistic, that some images are enhanced at certain points,” he said. “I would say social media literacy could help us guide us.”

The social media site has launched a series of new tools to combat mental health concerns. The Take a Break feature will send notifications after a certain amount of time reminding users to set the app aside, while also showing “expert-backed tips to help them reflect and reset,” the company said. In addition, parents will have greater abilities to monitor who interacts with their kids, from tagging them in posts to who follows them.

Ganson said body image issues should be treated as a “public health concern.”

“I think we need to also shift our focus a little bit towards educating young people about the risks of these behaviours and using social media,” he said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.