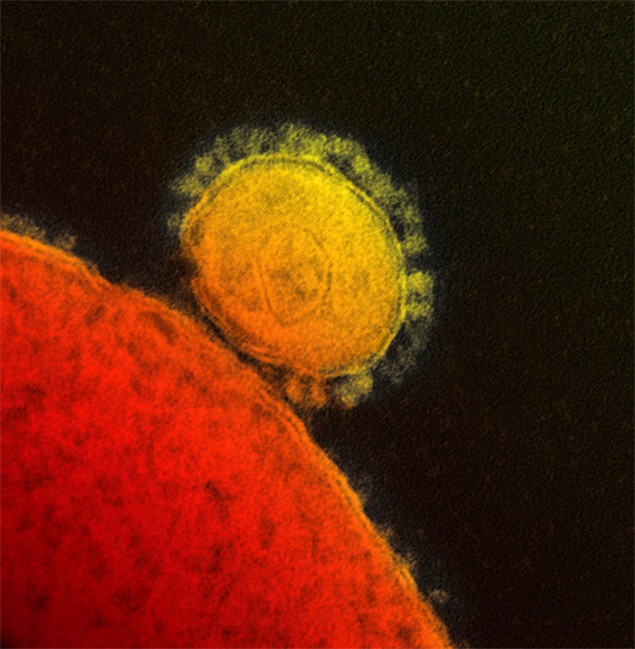

Scientists from Saudi Arabia and the United States have reported finding a partial match for the MERS coronavirus in a sample taken from a bat in Saudi Arabia.

The fragment of viral DNA was extracted from a fecal swab from an Egyptian tomb bat – the species’ proper name is Taphozous perforatus – in the western part of the country. The bat is an insect eater, and is often found among fruit trees because the fruit attracts insects.

The small fragment is a perfect match for the corresponding portion of the MERS virus isolated from Saudi Arabia’s first known case, a man who died in June 2012. The bat was found in a colony that roosted in ruins near where the man lived.

This the first time a match for the human virus – even a fragment of it – has been found in samples taken from an animal. But while the finding adds further support for the widely held suspicion that the new coronavirus originated in bats, the fragment isn’t large enough to say definitely that the bat virus was identical to the MERS coronavirus, an expert said.

If the scientists had been able to sequence the full genetic blueprint of the bat virus differences between it and the human virus might have been spotted, explained Andrew Rambaut, a professor of molecular evolution at the University of Edinburgh who has been following the MERS story.

“There’s still potential for it to be relatively distant if we had the complete genome,” he said in an interview.

“It’s definitely implicated in the story, but we don’t quite know where it lies in that story.”

- Invasive strep: ‘Don’t wait’ to seek care, N.S. woman warns on long road to recovery

- Canadian man dies during Texas Ironman event. His widow wants answers as to why

- ‘Super lice’ are becoming more resistant to chemical shampoos. What to use instead

- ‘Sciatica was gone’: hospital performs robot-assisted spinal surgery in Canadian first

The report was published online Wednesday in Emerging Infectious Diseases, a journal published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. It was reported by scientists from the Saudi Ministry of Health, Columbia University and the organization EcoHealth Alliance.

Lead author Dr. Ziad Memish, the Saudi deputy minister of health, said bats have always been suspected to be the original source of the virus, but there are probably other players of the chain of transmission that haven’t yet been identified.

“There must be something in the middle,” Memish said during a talk on MERS in Washington, D.C., that was organized and webcast by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Center for Health Security.

“Is it food? Is it (an)other animal reservoir? That’s something to be determined.”

The finding is one that senior author, Dr. Ian Lipkin, has publicly spoken about in the past. In early July, he said in an interview with The Canadian Press that he might not publish the results because of the limited size of the fragment.

It would have been bigger, but for a heartbreaking twist of fate.

Last October, researchers from Lipkin’s Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University and from EcoHealth Alliance gathered different types of samples – blood, fecal swabs and fecal pellets – from seven species of bats they found roosting in abandoned buildings near Bisha, near where the first Saudi MERS case lived.

The samples were shipped back to the United States for testing in Lipkin’s lab, which is famous for finding new viruses.

However, a mixup occurred at customs when the samples reached the United States. The material sat at room temperature for two days. All the samples, which had been shipped frozen, thawed. As a result, the material degraded. Lipkin’s team hoped to be able to extract more DNA from the sample, but they were unable to because of the poor state of the specimen.

Then a group of international scientists reported finding a coronavirus in a South African bat that was a close relative – the closest seen to date – to the MERS virus. Lipkin said he felt it was important to get his team’s finding into the scientific record.

“I looked at that and I said: ‘Well, that’s clearly not the closest match. If that’s what’s out there, we need to put this out.”‘

He put the finding in context this way: “Let’s say you’re looking for a fingerprint at a crime scene. And you’d love to get all four fingers, right? But you’ve got half of one finger and it’s a perfect match. That’s enough, if you have the rest of the evidence, to say yes, this was certainly somebody who was here at the scene of the crime.

“And that’s what we’re saying. This is a bat that clearly has a virus that is identical in this region (of the genome). So that’s good enough to make that link.”

Rambaut agreed the finding is important but noted it doesn’t help answer the key question about MERS: How are people being infected by a bat virus?

Many scientists believe, as Memish does, that another type of animal or animals is serving as a bridge, getting infected by bats and then transmitting the virus to people. But Rambaut believes it is possible that there is no other animal bridge. Bats might be infecting people indirectly by contaminating something people eat or drink, for instance.

“I think it’s a tantalizing clue, but it’s too early to say whether it is a virus that has given rise to that human case directly from the bat or whether there is an intermediate host that is spreading it through the area,” Rambaut said of the viral fragment.

More pieces of the MERS puzzle may come into focus soon. Lipkin said his lab has been testing blood and other samples from camels and other animals from Saudi Arabia and he expects to publish the results within a few weeks.

Suspicion has shifted to camels of late, after another group of scientists reported finding antibodies to MERS or a closely related coronavirus in camels in Oman and in the Canary Islands, off North Africa. As well, a few – though certainly not the majority – of people who have become infected with MERS reported having had contact with camels before they became ill.

Rambaut said the jury is still out on camels, suggesting that while they appear to be susceptible to the virus, it’s not clear they play any role in passing it to people.

To date there have been 97 confirmed cases of MERS and 46 of those infections have ended in death.

All cases have originated from four Middle Eastern countries – Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. MERS infections have also been diagnosed in Britain, France, Italy, Tunisia and Germany. But in these instances the virus was brought into the country by someone who had travelled in the Middle East before getting sick or who travelled to Europe by air ambulance seeking care.

Comments