By

Jeff Semple

Global News

Published June 11, 2021

11 min read

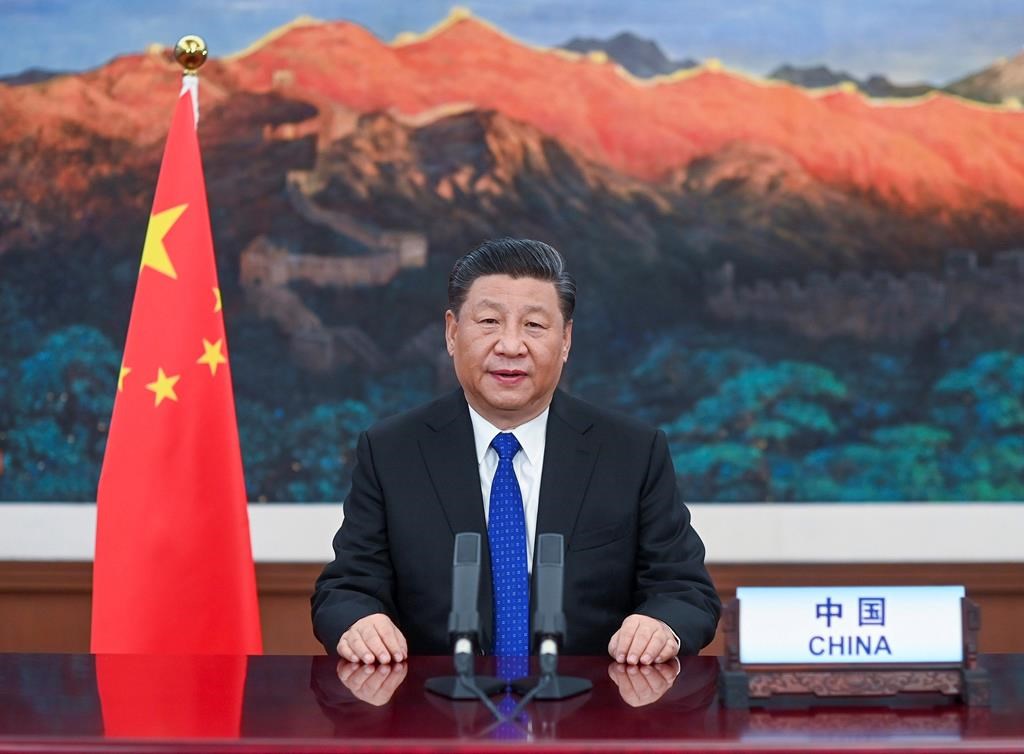

The 2017 Chinese film, Wolf Warrior 2, tells the fictional story of a Chinese soldier fighting to save an African country from an evil American mercenary. The Rambo-style blockbuster became the highest-grossing film in Chinese history and it has also inspired a new political term: ‘Wolf Warrior Diplomacy,’ used by some in China and the West to describe the Chinese government’s newly aggressive and combative foreign policy under Chinese President Xi Jinping.

On Episode 3 of China Rising, Wolf Warrior, we’ll discuss how Canada and its allies should respond to an increasingly bold and brazen Beijing by taking an in-depth look at China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ president; Xi Jinping is one of the world’s most powerful men, and yet people in the West know remarkably little about him.

“He is a major figure, but he’s also one of the world’s most mysterious individuals,” said Joseph Torigian, a China expert at American University in Washington, D.C., who is writing a biography on Xi’s father, Xi ZhongXun.

“One reason is that history in China is very hard to do these days is because Xi Jinping himself has stated that certain versions of history that are critical of the regime are dangerous to the Chinese Communist Party’s long-term stability,” Torigian explained.

While bookstores sell biographies on political leaders from Donald Trump and Justin Trudeau to Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un, it’s difficult to find a substantive biography on the current president of China.

“This is almost a tradition with Chinese leaders that they don’t see biographies written about the leaders while they are still in power,” explained Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C.

“If you want to write a biography, it is very difficult to have the complete story,” Yun said. “And I think with Xi Jinping, in particular, there’s also this factor of the narrative being closely guarded and being closely managed by a very complicated system of message control or the ‘propaganda department,’ if you will.”

But by combining Beijing’s official version of events with other interviews and known details from Xi’s early life, one can piece together an outline that offers some insights into the man who would become president.

Xi was born in 1953 into a life of luxury. He was a ‘princeling,’ a term that referred to the sons of China’s original revolutionary leaders. The country had just been through a brutal civil war and the Communists had won.

In 1949, their leader, Mao Zedong, declared victory and founded the People’s Republic of China. Mao became its ruler and Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

Xi’s father was a famous general, considered a war hero, and he became a high-ranking official under Mao. Xi’s family lived in a famous compound in Beijing, along with other Chinese leaders.

As a young boy, Xi was described by his teachers as a polite, shy bookworm. But around the age of ten, Xi’s father had a falling-out with Chairman Mao; he was stripped of his position, separated from his family and sent to do manual labour far away in the countryside.

A few years later in 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, to purge the Communist Party and the country of what he called capitalist “roaders” and influences. The revolution spiralled into a decade of chaos, destroying much of the country’s social fabric. Millions died.

At the time, Xi was just a teenager. His family’s house was ransacked, one of his sisters is said to have died by suicide and his mother was forced to publicly denounce both Xi and his father — her husband — as enemies of the state.

In 1969, Xi, along with around 16 million other young Chinese, the so-called “sent-down youth,” were loaded onto trains and sent to the countryside to work in the fields with the peasants.

Xi endured seven years of physical labour.

“A lot of people see that experience as significant in shaping his personality, shaping his approach to politics,” said Yun Sun. “The Cultural Revolution showed him how cruel power struggle could be in China, especially within the power centre. And there is a sense of ‘if you lose, you could lose everything.'”

Xi often talks about his time in exile and how it opened his eyes to the suffering of ordinary rural Chinese. Propaganda videos show Xi mingling with farmers, to highlight the president’s concern for the rural poor.

Xi’s government claims to have lifted nearly 100 million people out of poverty (though that figure was calculated using a poverty line that the World Bank applies to poor developing countries).

Torigian said the chaos of the Cultural Revolution also taught Xi that a strong central government and Chinese Communist Party were needed to hold the country together.

“What’s so interesting is that this individual, who for Western observers might seem like someone who would be upset with this organization that had caused him to go through all of those emotionally distressing experiences, was actually someone who took pride in what he faced, because in his words they were forging experiences,” Torigian explained.

“They were moments in time that not only allowed him to rededicate himself to the party, but also demonstrate his belief that the party was the only organization that could save China.”

After Mao died and the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, Xi returned to Beijing to study. His father was welcomed back into the Chinese Communist Party and became a champion of economic reform. In fact, Xi’s father became one of the first Chinese officials to visit the United States in 1980.

“For anybody who studies Chinese elite politics, the conventional narrative for a very long time was that, after the Cultural Revolution, the leadership in the party decided that it would be disastrous for another strongman to emerge. And in fact, Xi Jinping’s own father was of that particular opinion.”

Over the next three decades, Xi slowly climbed his way up the echelons of power, before being elected Chinese president in 2012. Many believed Xi would follow his father’s footsteps and push for reforms, by further opening China’s economy and drawing closer to Western democracies.

But some observers believe the events of 2008 may have dissuaded him. Xi and other Chinese officials watched as the financial crisis devastated the United States and its allies.

“And I think we see a very discernible shift in mentality and attitude among many of the elite leaders in China, including many of those who were very sympathetic to the United States and perhaps wanted to move their economy – if not their politics – more towards a Western model of development,” explained Tony Saich, a China expert at Harvard University who met Xi while he was vice president in 2007.

“And I think that really created a shock. And that idea that somehow the West is the master, we are the people who you should study, certain parts of it faded away and it became a much stronger confidence that perhaps what China was doing was best and that China could get it right.”

Xi’s backstory paints a picture of a man who has witnessed extreme poverty and political chaos, and who believes the best backstop against both is a powerful Chinese Communist Party.

“I think from his perspective, when he took power in 2012, China looked an absolute mess,” Saich said.

“Corruption was endemic. Local government, local society seemed to be pursuing its own interests with little attention to what Beijing was intending or Beijing was pushing. And I think as he looked around at that, I think he thought that unless there was strong central control through a unified Chinese Communist Party, China would be in trouble.”

After Xi took power, he wasted no time tightening his grip. Xi’s political philosophy, called ‘Xi Jinping Thought,’ is now enshrined in the constitution. In 2018, Chinese lawmakers abolished the five-year term limits, allowing Xi to remain president indefinitely. He’s now widely considered to be China’s most powerful leader since Chairman Mao.

“Xi Jinping has been particularly successful and skillful in playing the political game, in aiming at his political opponents and gradually removing them from their power,” said Yun.

Another one of the hallmarks of Xi’s rule has also been a zero-tolerance approach towards anyone who dares to challenge his government and its policies, by cracking down on dissent both at home and abroad.

The arrests of the ‘Two Michaels,’ Canadians Kovrig and Spavor, in December 2018 are widely seen as retaliation for Canada’s arrest of Chinese telecom executive Meng Wanzhou at the request of the United States. Beijing also temporarily blocked billions of dollars in imports of Canadian canola, beef and pork.

Jeremy Paltiel, a China expert at Carleton University, says Beijing is punishing Canada to send a message.

“The Chinese expression is ‘killing a chicken to scare a monkey,’ that faced with the pressure from the United States and the attack on China’s trade, China wanted to make clear at that time that if people would follow Donald Trump’s way, there would be consequences for it.”

Those consequences have sparked a debate in Canada over how to respond. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has tried to walk a fine line, talking tough at times, but also unwilling to take any real action against China.

An Ipsos Poll for Global News last year found Canadians are similarly torn: around half said Canada should be careful not to offend the Chinese government and risk further retaliation, while the other half disagreed and wanted Ottawa to take a tougher stance.

One thing both sides agreed on: 82 per cent of those polled said Canada should reduce its trade reliance on China.

“There is no doubt that there has been a collapse of trust,” said Paltiel. “And yet we live in a world which is profoundly interdependent. Probably three out of four packages that arrive on your doorstep that you’ve ordered contained stuff that’s been made in China and will continue to be made in China. Our prosperity does depend on having some relationship with the growing prosperity of China.”

China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner — albeit a distant second behind the United States. Last year, China accounted for 14 per cent of Canadian imports and less than four percent of Canadian exports.

“Canada’s economic dependence on the Chinese regime is not as great as most people think,” argued Charles Burton with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute think tank in Ottawa.

“It seems to me that so long as the government only condemns the Chinese violations of the international rules-based order in diplomacy and trade and human rights by simple lip service or virtue signalling — simply saying Canada is very concerned or we would like an investigation of this or that, but we don’t take any effective retaliatory measures — that this emboldens the Chinese regime to do more of this kind of thing.”

For a lesson in what can happen when a mid-sized country decides to challenge China, one need only look Down Under. Australia has become Beijing’s favourite political punching bag, banning a long list of imports, including Australian barley, wine, beef, cotton and coal.

Chinese officials recently provided Australian reporters with a list of 14 reasons why Beijing is angry with Canberra, including Australia’s early calls for an inquiry into the source of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Australian journalist Hugh Riminton.

“When there are criticisms that need to be made about China, people have learned from the Australian experience that it’s unwise to go as a single nation and criticize China because you’ll be picked off,” Riminton said.

As a result, Western allies are now talking about locking arms. U.S. President Joe Biden is focused on building a coalition of countries to stand up to China.

In March of this year, the U.S., EU, U.K. and Canada came together to pass joint economic sanctions, targeting a number of Chinese officials for their alleged role in persecuting China’s Uyghur minority.

“The Biden administration, perhaps wisely, has thought that the United States can’t take on China by itself, but would do much better with its European allies, with its Asian allies; and has been steadily, quietly trying to explore ways that jointly, collectively they can bring pressure on China to change its behaviour,” explained Steven Myers, the New York Times’ Beijing Bureau Chief.

“China sees that as an inevitable threat. It’s doing its best to try to block that, to split the allies when they can. But it’s also very happy to compete and show that they have their own allies that they can turn to,” Myers said.

Senior Chinese officials have held a flurry of meetings in recent months with their Russian counterparts; Russian President Vladimir Putin described ties between the two countries as being at the “best level in history.”

China is also investing heavily in fostering relationships with poor and developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, offering support from loans to Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines.

“And I think that if you talk to most thoughtful Chinese officials … their intention is not to alienate themselves from the world, but they’re demanding respect and it’s respect on their terms,” Myers said. “They’re not just saying, ‘respect us and hear us out.’ They’re like: ‘do what we want.’ And right now, looking around the world, it seems to be working.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.