The first five days of Gavin Zima’s new job were uneventful. The sixth day — February 12, 2014 — changed everything.

The young man, with a loving family and so much promise, died that day. While he lived another seven years, the life that he had previously lived was over.

As the opening line of his obituary from this past April so painfully and honestly pointed out: “Gavin Paul Zima, 33, of Edmonton, Alta., took his own life to end his chronic pain and suffering after struggling with multiple injuries in a crippling work accident that left him with a broken body and mind for the past eight years.”

Zima is one of thousands of Canadians that suffer workplace injuries. The public usually hears about the large, dramatic accidents and we sometimes know about the workers who are killed.

But many of those that are injured suffer in silence and anonymity, their lives altered forever.

That was Zima’s story.

Early years

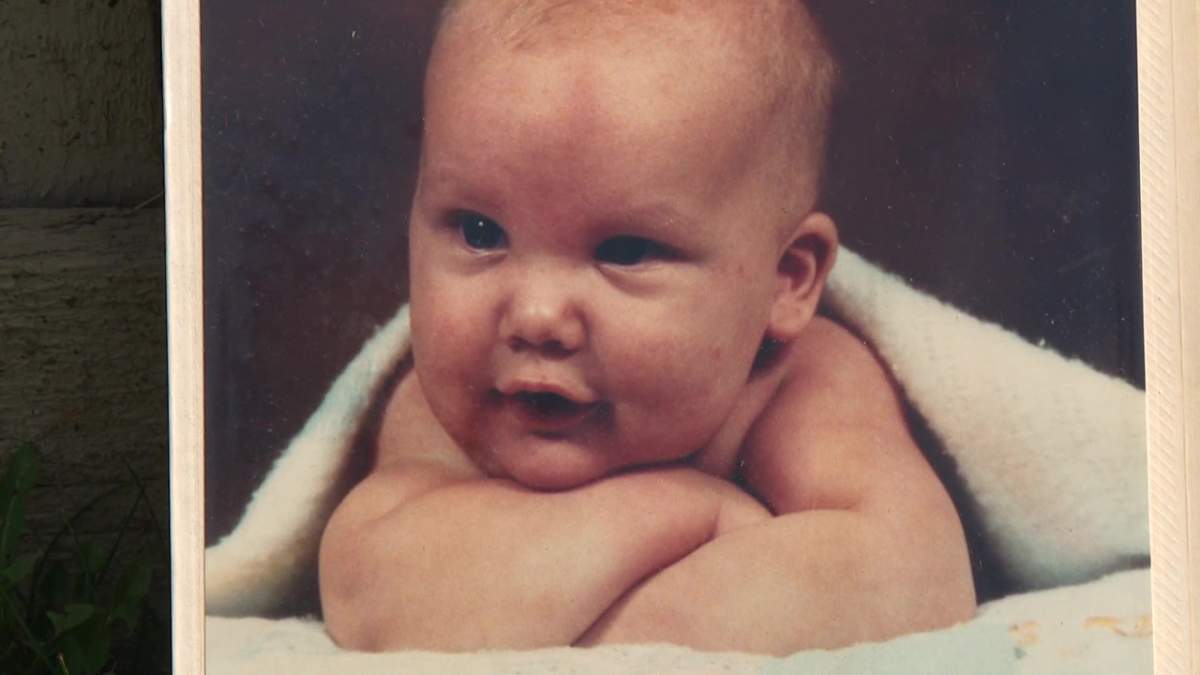

MaryAnn Reinke was 10 months pregnant when Zima was born on Aug. 20, 1987. She said her son took his time entering the world, but moved quickly through the rest of his milestones.

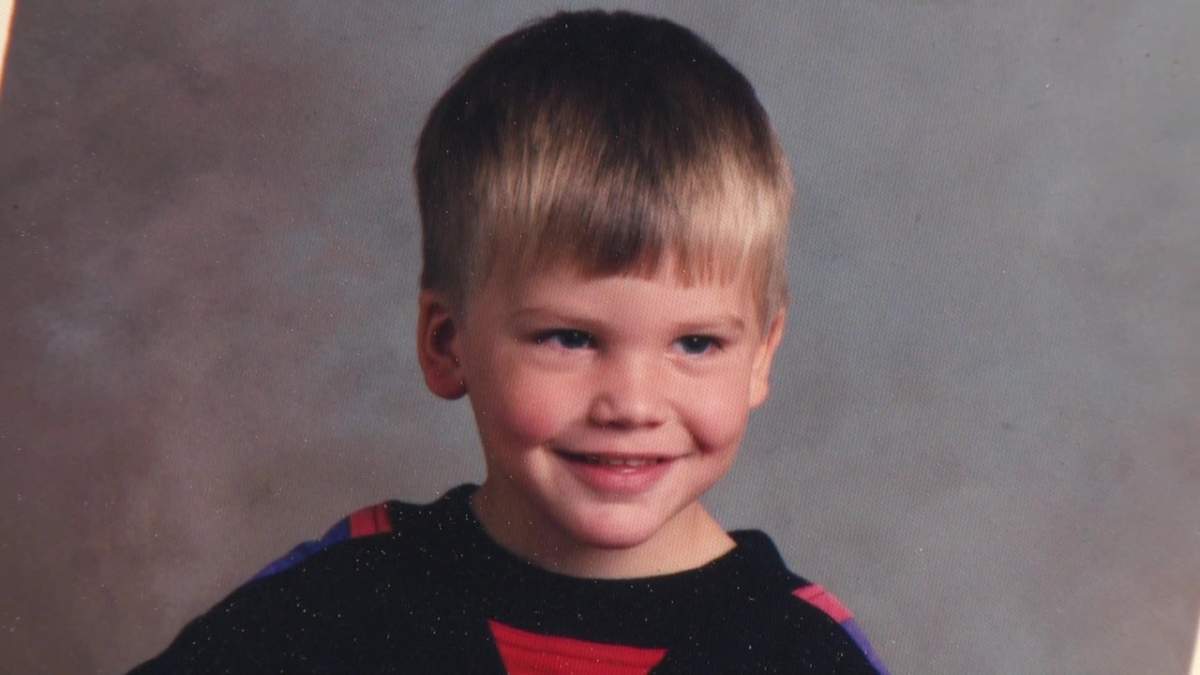

“He was such a happy kid. Nothing bothered him. He was naturally bright and strong,” she said from her Spruce Grove home. “He’s six years old, playing with his siblings and he’s almost beating them at a hockey game!”

Adored by his older brothers and sister, his family said Zima had a heart of gold — and a particular love for his two dogs, Gav and Beagrr. Reinke said he treated the pair like his own children.

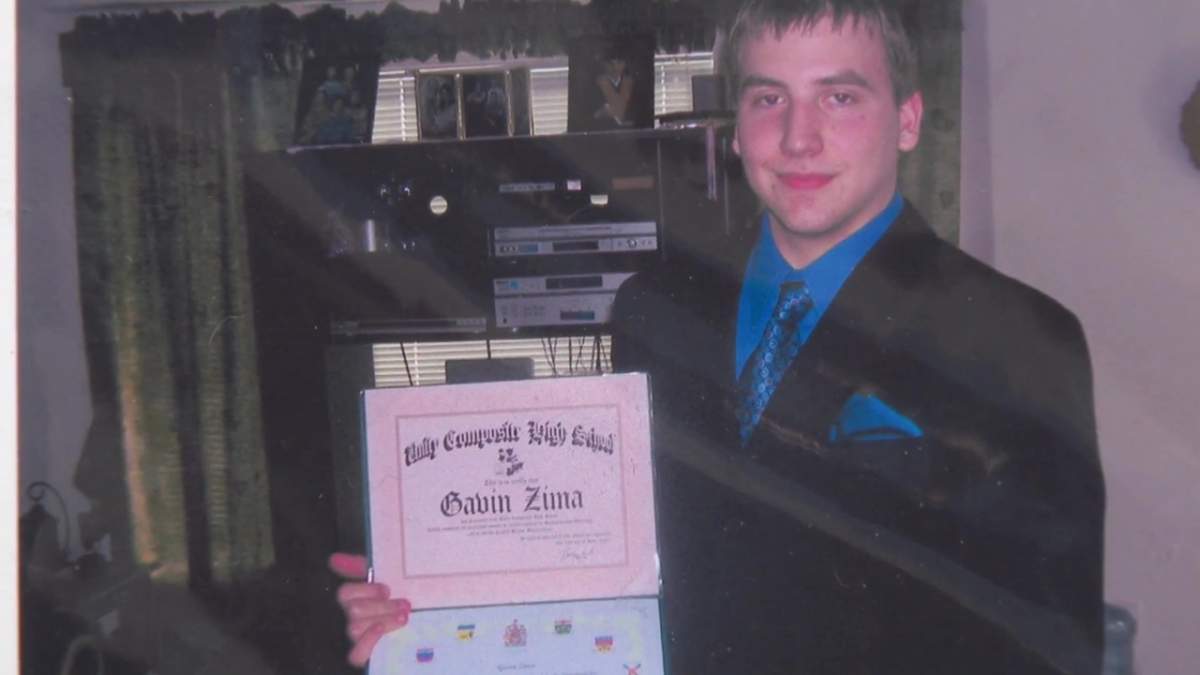

Zima graduated with honours from Unity Composite High School in Unity, Sask. After graduation, he went into sprinkler systems and installation.

“He was so hard-working. He was extremely well-respected,” she said. “Even though he was busy, he still made time for me. You know, ‘Mom do you need anything before I go? Can I help you?'”

“He was just so determined,” Reinke said. “He made goals and he stuck to them. My neighbours would come up to me and say, ‘How do you get your teenager up at 6 a.m. every morning? I can’t get mine off the couch.'”

Zima received his Alberta Journeyman certification in sprinkler systems and installation, but after eight years in the field, he was ready for a new challenge.

Devastating crash

Zima had travelled to Saskatchewan from Edmonton to work as a pipeline inspector. He was early in the trade, but a quick learner.

“As much as my company liked me… Gavin was the real rock star,” his older brother Sheldon Hildebrand said. “I was really excited to see how he was going to excel… he was already so good a few days into the job.”

At the end of a snowy shift in February 2014, Zima was driving down Highway 1 in Saskatchewan when a blizzard hit.

Get daily National news

“They were going 30 km/h with their hazard lights on,” Hildebrand explained. “There was a (Chevrolet) Suburban on the side of the road and Gavin hit its mirror.”

Hildebrand said Zima wanted to check if anyone in the vehicle needed help.

In an unmailed letter written to AISH in 2019, Zima detailed what happened next.

“I was first hit from behind by a tow truck travelling 100 kilometers an hour, which caused my initial injuries,” Zima wrote.

“I was then carried several hundred feet by first responders to an ambulance where I was loaded onto a stretcher.”

As the paramedics began to load Zima onto the stretcher, a semi-trailer lost control and hit his stretcher, launching him several hundred feet away.

“The semi-trailer jackknifed and broke the ambulance in half. It broke the pelvises of both paramedics,” Zima wrote.

“A second ambulance arrived and those paramedics went to retrieve my body, thinking I was dead, only to find me still conscious.”

Zima was in hospital for two weeks. A broken sternum, legs and vertebrae made the 26-year-old feel like a stranger in his own body. He would later be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

Reinke said her son was unable to enter a vehicle or travel for long periods of time due to high levels of anxiety.

Workplace accidents

Hours after the crash, Zima applied for support through the Workers Compensation Board (WCB) and worked to heal his body and mind.

While his case was complicated by the cross-provincial nature of his employment, turning to the WCB for support is done by thousands of Canadians every year.

Zima was one of thousands of people injured on the job left with long-term effects. In Alberta, 18,000 workers are currently receiving ongoing benefits and services for workplace injury claims registered at least five years ago.

In total, WCB Alberta has received more than 600,000 claims over the past five years.

Of those 18,000 workers, about 60 per cent are receiving wage loss payments such as a pension. The remainder receive only non-wage benefits like ongoing medical treatment, medications and tools like hearing aids.

In 2020, fewer than 30 per cent of workers who reported claims missed time from work due to their injuries. The average lost-time claim is about 60 days.

Zima’s accident initially left him in a wheelchair with numerous braces due to a broken leg and back. Over time he progressed to a walker, then crutches and finally a cane.

Reinke said Zima was cleared by WCB as ready to return to work about two years after the accident — he had a job lined up as a warehouse manager in Saskatchewan once he recovered from his PTSD — but she said he was far from ready.

Changes in Gavin

As his prognosis became clearer, Zima realized some of his injuries would require long-term, even life-long care.

“The doctor told him: ‘You will always have a cane. You will always be in pain. It’s chronic pain,'” Hildebrand said.

“Afterwards, he lived in my mom’s basement. He was scared to get in the car. He couldn’t move until noon when his pain pills kicked in.”

“He had to sell his truck because he couldn’t drive it anymore. He lost total use of his right leg,” Reinke said. “He couldn’t even go and get a coffee for himself.”

Still suffering, Reinke said her son made her hide all of the photographs of him from before the accident.

“I had placed the photographs so he could see them better,” she said. “He said, ‘You know, this just hurts me.'”

Once an eternal optimist, his mom said the “loving, caring and fun” Zima receded into himself.

“I kind of didn’t want to talk to Gavin after because it made me sad about who he was… before and after,” Hildebrand said.

“The accident took him away. We didn’t have Gavin anymore,” Reinke said.

Final years

“At one point he said, ‘I don’t want this pain and I don’t want this fight anymore.’ Then, for two years after he didn’t talk about it,” Reikne said.

Reinke said she created the most positive and loving environment possible for her son as he battled depression and chronic pain under her roof.

Gavin died by suicide on April 12 in Spruce Grove. He was 33 years old.

“I’m so sorry mom, I tried my hardest to keep going — to take care of you and the dogs longer. I just can’t do it,” Zima’s last note to Reinke read. “I love you more than words can ever express.”

“Sure, he’s a strong, tough guy — but he’s not on the inside. It broke him,” Reinke said.

Where to get help

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, resources are available. In case of an emergency, please call 911 for immediate help.

The Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention, Depression Hurts and Kids Help Phone 1-800-668-6868 all offer ways of getting help if you, or someone you know, may be suffering from mental health issues.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.