One year after the first cases of COVID-19 were detected from Canadian jails, community activists say those behind bars are still not being protected from the virus.

With signs reading “Free them All,” roughly 50 people rallied outside of Maplehurst Correctional Complex in Milton. Through a car caravan, the group then made their way to the Toronto South Detention Centre, where they further protested against prisoners’ current conditions. The event was held by the Toronto Prisoner’s Rights Project, a collective of individuals with lived experience, prisoner’s loved ones and those who have been impacted by carceral violence.

“Folks are dying inside. Folks are being severely impacted by the virus, by the pandemic. Their loved ones on the outside are also being impacted,” said Gabby Aquino, a member of the group.

“It’s not just the virus and the pandemic that’s the problem, it’s the prisons themselves.”

Aquino says prisons are not built for incarcerated individuals to survive the pandemic.

“We’ve heard stories of folks inside being denied PPE because it’s being considered contraband. We’ve heard of folks being placed in isolation for months on end.”

She adds visitations have been suspended, preventing families from seeing their loved ones inside, and those imprisoned have been facing challenges when it comes to contacting legal counsel.

- Mother of B.C. mass shooting survivor shares update, says breathing tube removed

- Canada halts deportations to Israel and Lebanon amid ongoing conflict

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

- Carney says former prince Andrew should be removed from line to throne

Rajean Hoilett, who is also a member of the Toronto Prisoner’s Rights Project, says his brother was incarcerated during the pandemic. Hoilett says he was highly concerned for his well-being.

“It’s been heartbreaking to go weeks without calls, not knowing what’s happening, not knowing if your loved one is safe,” he said.

Hoilett says the group has been in touch with current prisoners, who say treatment towards them has been “inhumane.”

“Folks are protesting for basic human needs, for access to clean air, access to clean laundry, personal protective equipment,” he said.

Get daily National news

He adds the restrictions have left “people locked down in their cells for two weeks at a time.”

“(That’s) with maybe a day out,” Hoilett said. “Sometimes people are (getting) two hours of fresh air within two or three weeks time (based on) some of the stories that we’ve heard.”

Both the Milton and Toronto institution have experienced the worst COVID-19 jail outbreaks in the province. As of March 18, there have been 34 active inmate cases at the Toronto South Detention Centre.

Similar rallies, themed “Free Them All: National Day of Action,” were held in various cities across the country Saturday. The protests come at the same time as a report revealed increased incarcerations since the start of the pandemic.

The report was released by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, in partnership with The Centre for Access to Justice and The Criminalization and Punishment Education Project (CPEP). It cites that while drastic measures were taken during the first wave of the pandemic to decrease Canadian prison populations, numbers have been increasing since.

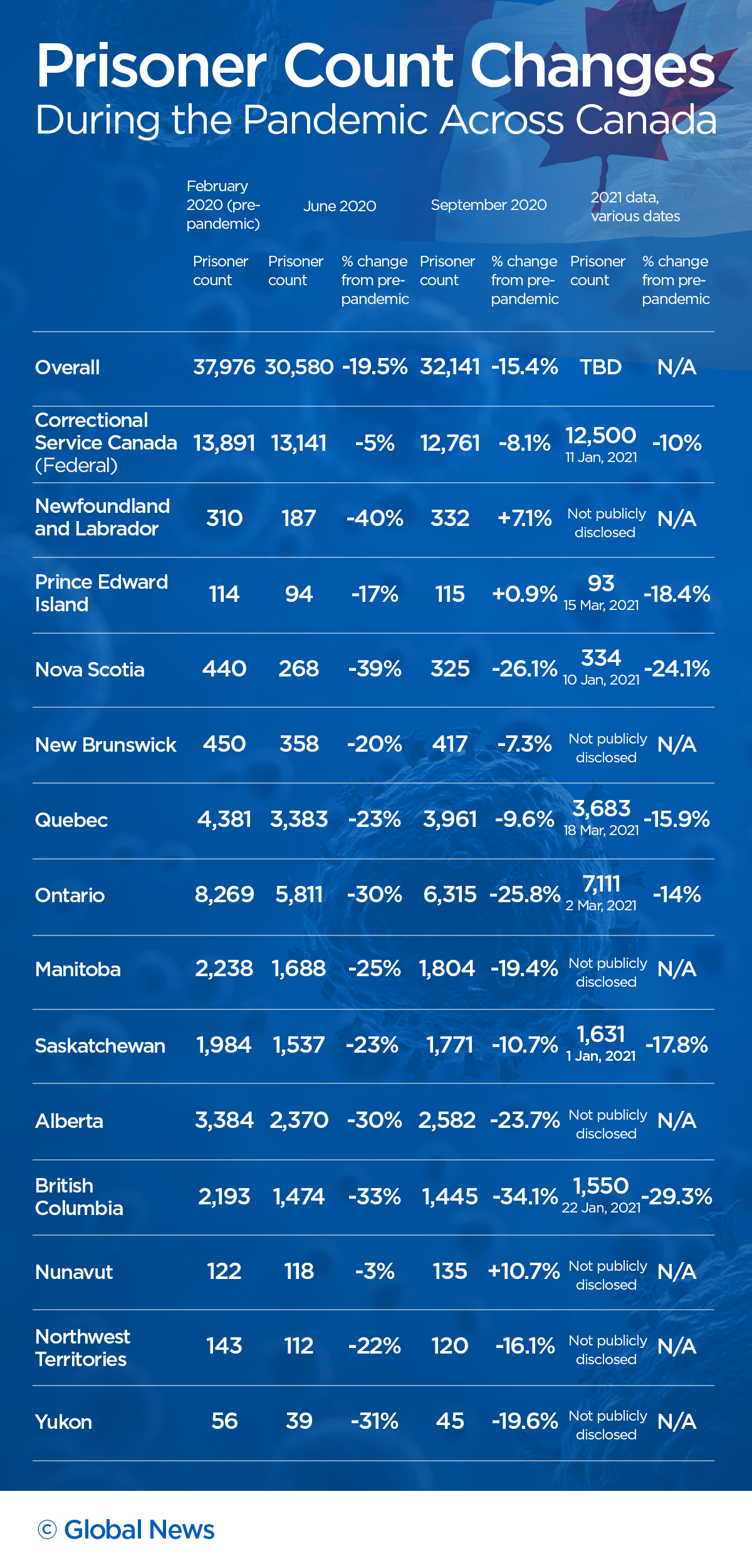

Overall, Canada’s incarceration count dropped from 37,976 to 30,580 during the first wave. In September 2020, that number rose to 32,141.

Ontario’s incarceration count dropped 30 per cent during the first wave. As of March 2021, it has increased by 16 per cent.

Justin Piché is an associate professor with the University of Ottawa’s criminology department and part of CPEP. He says the data shows since the start of the pandemic, seven thousand cases have been linked to Canadian provincial and territorial jails, prisons and penitentiaries. Five thousand of those cases have come from incarcerated individuals, and six prisoners have died from the virus.

“Right as the second wave was getting ready to take off, jurisdictions took their foot off the gas. The provinces and territories started imprisoning more, so jails started filling back up right when COVID-19 was transmitting more in our communities,” said Piché.

He adds, as a start, individuals convicted of non-violent crimes should be released.

“Prison authorities should have reviewed every single prisoner in their care to see whether or not they could be safely released into the community and see what those assessments say and release people based on those kinds of evaluations,” he said.

“A number of folks can be safely released into the community, sometimes without community support. They may have homes to go back to, others may not. So if they’re provided with housing, income support and other kinds of supports in the community, they can live safely among us.”

According to the report, which uses the latest information from Statistics Canada, 600 of those behind bars in the country have been vaccinated, which Piché says is a far cry from how many should be getting inoculated.

“We have a lot of work to do,” he said.

The report shows most provinces have planned for prisoners to get their shots in Phase 2 of the vaccine rollout. It says no plans have been disclosed for Quebec, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“Prisoners need to be vaccinated sooner than later, and the same goes for prison staff,” said Piché.

A spokesperson for Ontario’s office of the solicitor general told Global News, “The Ministry of the Solicitor General is working with its partners to keep provincial correctional facilities and our communities safe during the COVID-19 health emergency.”

The ministry adds they have made changes across all provincial correctional institutions, including the “decision to give temporary absences to intermittent inmates who serve time in custody on weekends, allowing them to serve their time in the community.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.