When something goes amiss at the Moosomin First Nation water treatment plant, Nathan Martell is often the man who gets a call.

Whether it’s a power outage in the middle of the night or a broken part on a weekend, Martell or one of his two co-workers, who are often on call, will troubleshoot from home or the plant to make sure the 238 homes in their community have access to safe drinking water.

Martell received his certification in water and waste water management nearly two decades ago and started working at the Moosomin water treatment plant in 2003. His skills are in high demand across Saskatchewan, and it wasn’t long before he was hired to work in waste water treatment at the City of North Battleford, roughly 40 kilometres south of Moosomin First Nation. The pay was better and Martell also got a pension and benefits — perks his First Nation could not afford.

Despite landing the new, more lucrative job, he continues to work at the Moosomin water plant, largely because there’s no one else to take over for him if he leaves.

“The big thing for me is, it’s our community,” he says. “We grew up here and my family’s from here and if they’re not getting good quality water, then that drives me … I don’t want nobody to get sick or anything to go wrong. And it’s my home. You can’t turn your back on home.”

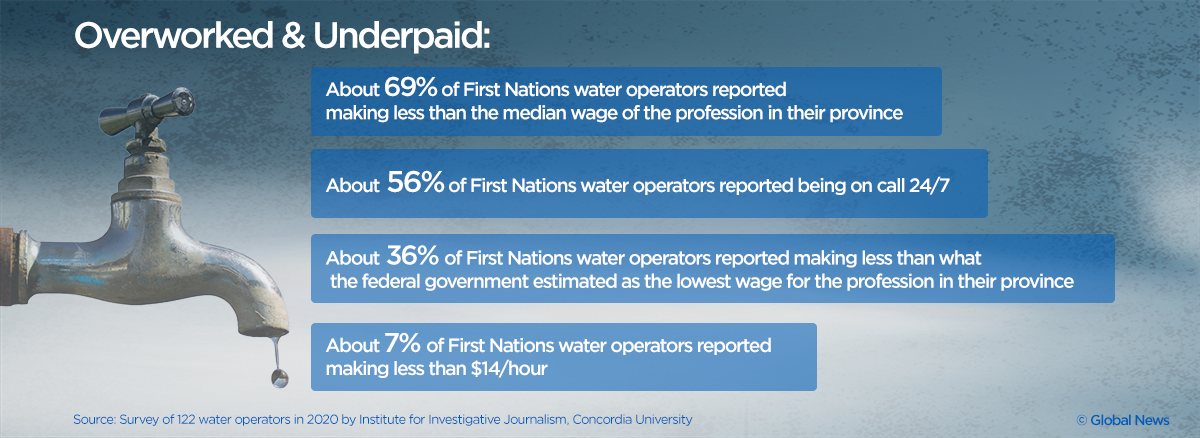

Martell is not the only one working long hours for low pay at an on-reserve water treatment plant.

A consortium of universities and media outlets led by Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism conducted a survey of water plant operators, managers and public works employees from 122 First Nations across Canada in 2020. The consortium, which includes the University of Regina’s School of Journalism and First Nations University of Canada Indigenous Communication Arts, found that two-thirds of water operators on those First Nations were earning lower than the median wage of operators in their province — sometimes close to minimum wage — while often on call 24/7.

That’s in part because, even though the federal government has known for years that First Nations are underfunded for the operation and maintenance of on-reserve water and waste water systems, Indigenous Services Canada hasn’t updated its funding formulas since 1998.

Water systems underfunded

Rebecca Zagozewski is the executive director of the Saskatchewan First Nations Water Association, a non-profit organization that works to build First Nations’ capacity to take care and control of their own water services. She says recruitment and retention of water treatment plant operators is a “real problem” on Saskatchewan First Nations, largely because First Nations often can’t pay operators competitive wages.

That means some water operators are stuck in essential jobs feeling unsupported and with no replacement if anything goes wrong. Many First Nations operate in this state, with the safety of their drinking water reliant on just one or a few underpaid and overworked operators.

“I know some operators that have been in the same position, operating the same water plants for 20 years, and never got a raise, never get vacation,” Zagozewski said.

Water services on First Nations are largely funded by Indigenous Services Canada, but Zagozewski says the money provided does not reflect present-day costs of running water treatment plants and paying staff appropriate wages.

After Justin Trudeau’s Liberals took power in 2015, the federal government promised it would end all long-term boil-water advisories in First Nations communities — those lasting longer than a year — by March 2021. The government has since acknowledged that timeline will not be met.

Since 2015, more than $1.74 billion of targeted funds has been invested to support water and waste water projects on reserves. However, most of it is intended for new construction and major upgrades, not operations and maintenance (O&M), the umbrella term for the day-to-day activities that ensure residents receive safe drinking water.

O&M costs include the salaries of the water operators and public works personnel who work in water treatment plants and distribution systems, as well as the cost of replacement parts, supplies, chemicals used to treat water, electricity and inspections.

Between 2015 and 2018, federal spending on water- and waste water-related O&M averaged $146 million per year, according to data provided by ISC to the consortium. However, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated in December 2017 that annual O&M needed to be $361 million, rising to $419 million if different projections for population growth are used.

Read more: Many Saskatchewan First Nations residents are travelling hours to get coronavirus treatment

The consequences of insufficient funding extend beyond operators’ salaries.

In a 2018 presentation obtained by the consortium, ISC officials suggested underfunding of O&M contributes to infrastructure failing prematurely. ISC’s 2017-18 annual departmental results report noted that only 77 per cent of inspected water and waste water systems on reserves were “projected to remain operational for their life-cycles.”

Nearly 23 per cent of respondents to the consortium’s survey said they don’t have enough funding to run their water treatment plants and distribution systems. Another 11 per cent expressed other funding-related concerns — for instance, that it can take a long time for funds to be unblocked when emergency repairs are needed.

Shoestring budgets leave First Nations little choice but to “juggle funding around,” said Mervin Lathlin, the operations and maintenance manager for Shoal Lake Cree Nation, 210 kilometres east of Prince Albert.

In his community’s case, bill payments sometimes get delayed. He said there have been a few times when shipments of chemicals used in water treatment were held up by a local supplier after Shoal Lake wasn’t able to settle a bill in a timely manner.

Get daily National news

“That’s when I start panicking,” he said.

On one occasion, he was able to borrow chemicals from neighbouring Red Earth Cree Nation to hold him over until he received his shipment.

Change to funding models slow to come

ISC’s funding formula has long included a requirement that First Nations cover 20 per cent of O&M-related costs for water and waste water infrastructure, including operator salaries. But reports by both the government and external organizations have noted for years that many First Nations struggle to come up with their share, unable to charge much in user fees for water services because of the high costs of living and unemployment levels in their communities.

Minister of Indigenous Services Marc Miller said last year that the federal government is moving to fully cover the calculated O&M costs of on-reserve water- and waste water-related facilities, and additional funds are expected to be rolled out by the end of this fiscal year. However, this does not address the concerns that the funding formula does not sufficiently capture the costs of running the facilities.

Read more: Indigenous minister says racism in health care can’t be fully addressed without provinces

ISC’s existing O&M policy was developed in the 1980s. There is almost universal consensus that it’s antiquated and inadequate. Experts say the current funding model hasn’t kept up with the pace of technological progress or changes in labour market conditions.

“It’s not really based on what the real cost is to sustain that asset. It’s based on this funky, 30-year-old model that was developed when infrastructure was light years simpler than it is now,” said Craig Baker, the general manager of First Nations Engineering Services Ltd., a Canadian Indigenous-owned firm that has designed water infrastructure for many First Nations.

In 2017, then-Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett and Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde agreed in a joint statement that ISC’s O&M policy was “outdated, and does not reflect First Nations needs.” The federal government and the AFN have been working on reforms to the policy and other aspects of the fiscal relationship between Canada and First Nations ever since.

While neither side can yet provide a timeline for the reformed policy’s implementation, a general strategy has been agreed upon — one that would allocate funding based on the costs each First Nation actually incurs and what’s needed to make infrastructure last as long as possible, not a one-size-fits-all formula.

“We’re working to change that formula and I think this is what communities want,” Miller said in an interview in December, weeks after the federal government announced that Canada would miss its March 2021 deadline to lift all long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities.

However, the government said it was committed to working with communities long-term to address O&M concerns. The 2019 federal budget included $605.6 million in new funding over four years, beginning in the 2020-21 fiscal year, for the operations and maintenance of on-reserve water and waste water systems, according to a statement from ISC.

Read more: Indigenous Services minister says Trudeau government won’t end boil-water advisories by March 2021

In December, Miller announced more than $1.5 billion in additional investments for on-reserve water infrastructure, including another $616.3 million over six years and $114.1 million per year ongoing thereafter to support O&M.

“If you want to ask me about what I thought about the old formula, I think that the funding commitment (in December) shows what I think about the old formula,” Miller said.

“These additional funds, in part, are expected to assist First Nations in their ability to retain qualified water operators,” ISC said in an emailed statement.

While waiting for new funding to roll out, First Nations have been making do with what’s available to them.

The Saskatchewan First Nations Water Association did a survey of Saskatchewan First Nations water operators in September 2019. Only 18 people responded, reporting a wide range of salaries, from $20,001 to $60,000 annually. By comparison, the median salary for water operators in Saskatchewan is roughly $57,000, according to the federal government’s data. Most respondents of the survey also indicated they worked overtime or were on call several hours during a typical week. The lower an operator’s salary, the more likely they were to do so.

In its statement, ISC said that while responsibility for safe drinking water on reserves is shared between First Nation communities and the federal government, First Nations are the owners of their water and waste water systems and responsible for their daily operation and management.

“As such, water and waste water operators are employed by First Nations and operator salaries are determined by First Nations. ISC recognizes that First Nations communities face challenges with recruiting and retaining operators, which is why we continue working with First Nations to assess their needs and ensure operator salaries are factored in when determining funding allocation,” the statement read.

Moosomin First Nation Chief Bradley Swiftwolfe said he has about $40,000 a year to pay the three employees at his community’s water treatment plant.

“We’re very fortunate to have Nathan and (the other operators) because they really don’t get paid according to everybody else, I’d say, on a national scale. They’re kind of doing it as a favour to their community,” he says.

Health risks

Deon Hassler used to be a water treatment plant operator at Carry the Kettle First Nation. Today he is a board member with the Saskatchewan First Nations Water Association and a circuit rider with the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council, which means he travels to 11 First Nations to assist their water treatment plant operators as needed.

The job keeps him busy — he says he has been on call 24/7 and hasn’t taken a holiday since he started in 2013.

He says there is “a constant turnover” of water treatment plant operators in his communities. It’s tough to hire backup operators, and he knows five operators who want to retire, but feel they can’t, he says.

“Trying to get them to stay at the water plant, for these operators, really isn’t that enticing because it doesn’t pay very well.”

It can be easier for First Nations to get money from ISC for the capital costs of water treatment plant upgrades or replacements than to get more operational funding to support operators, Hassler says. Sometimes, First Nations can’t attract qualified operators, so they hire people without the necessary certifications who end up in over their heads.

“You’ve got an operator who’s not doing his job, not doing his maintenance, but he’s getting a brand new water plant. So I’ve seen little scary things,” Hassler says. “To me, I just don’t get why it happens that way sometimes.”

If operators are not properly trained, the results can be devastating. In 2000, an E. coli outbreak in Walkerton, Ont. caused 2,300 people to fall ill and seven to die. An inquiry into the incident, in which E. coli infected the water system from a nearby farm, found that the water operators lacked the training to adequately treat the contaminated water.

In 2005, hundreds of residents of Kashechewan First Nation in Ontario were evacuated to nearby towns because of high levels of E.coli in the water. Although their water treatment plant was new, the operators weren’t adequately trained to run it and added too much chlorine to the system to counteract the bacteria. The high chlorine led to chronic skin disorders in the population; Health Canada had to intervene.

While providing money for new water treatment plants is part of the solution, Hassler says more needs to be done to address gaps around water services on First Nations. He wants the federal government to make more money available to First Nations so they can pay water treatment plant operators appropriate wages and also pay trainees.

Aging plants

Zagozewski and Hassler say another reason leading to water treatment plant operator burnout is that some plants are too old and have frequent breakdowns or are inappropriate for the conditions.

Some operators report that they don’t have enough money to do preventative maintenance on plants, which leads to frequent problems and stress for employees.

“I find that a lot of times, it seems like the feds will build a lovely plant, but they don’t realize that the nicer the plant is and the more up-to-date it is, the more money it will cost (a First Nation) to run it,” said David Swift, a water operator at Thunderchild First Nation. Swift is an independent contractor and is not a band member.

“Our pumps are a little more expensive than some of the ones in older plants. Our electronic controls are expensive. And if we have problems with them, then they are expensive to replace,” he added.

In Saskatchewan’s southwest corner, Nekaneet First Nation has been struggling to keep a seven-year-old plant up and running. Tim O’Flannigan, who was the project manager for Nekaneet’s water treatment plant, said there isn’t enough money to buy spare parts or equipment — extra water pumps, for instance — in order to have them ready for when something inevitability breaks down and needs replacement.

“There’s no money for that stuff,” he said.

At one point, most plants on Saskatchewan’s 74 First Nations were green sand filtration plants. While these perform well when source water is clean, Zagozewski says they struggle if communities have to deal with high levels of contaminants, including iron and manganese. Some of those plants have since been replaced with biofilter or nanofiltration systems, including at Moosomin First Nation, which had its greensand filtration system replaced with a biofiltration system in 2014.

Hassler says when communities have old water treatment plants or ones that aren’t appropriate to deal with source water, it results in more work for operators.

“For some communities, as high as iron and manganese levels are, the guys would have to backwash their greensand filters four times a day (by reversing the flow of water through the filters). And can you imagine having an operator backwash four times a day? It means he has to stay there all day,” Hassler says.

“And then, when you have things that happen with that, it creates other breakdowns and other equipment problems and other water plant issues.”

James Cappo, 66, has been the water treatment plant operator at Muscowpetung First Nation since 2004. The First Nation has two water treatment plants, both of which use the greensand filtration system. He says the main plant was built in the late 1990s and hasn’t had significant upgrades since. While renovations were planned for last year, those were delayed because of the pandemic.

“This is an old system and it breaks down,” Cappo said. “One year, my pumps gave out. They were so old they were rusted right through.”

Cappo, who is on call at all hours, says he worked alone at the plant for years before a trainee started working with him in the fall of 2019. Cappo says the job can be stressful and there have been times when he’s had to work through the night to make sure the plant runs properly.

If he were to get sick tomorrow, his trainee would need to run the plant, even though he is not a certified water plant operator, he says.

“I can’t afford to get sick.”

While Cappo knows he could make more as a water treatment plant operator off reserve in a larger community, he says he has no interest in looking for other work. His band tops up his pay beyond what is provided by ISC and he is satisfied with what he earns. He also appreciates that the band made money available to pay his trainee.

“I just got home too when I got this job and, now that I’m home and I’m up in age, I think I’ll just stay here,” he says.

He doesn’t plan on retiring anytime soon, but hopes his trainee will be able to take over for him when the time comes.

On Moosomin, Chief Swiftwolfe says he’s “definitely concerned” about what will happen when his water treatment plant staff finally retire. The band has been talking about the need to train new people to work at the water treatment plant for years.

“But we didn’t find any yet,” he says.

— This reporting was done in partnership with a consortium led by Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism that includes Global News, APTN News, the University of Regina School of Journalism and First Nations University of Canada Indigenous Communication Arts (INCA).

Investigative team:

Institute for Investigative Journalism reporting fellowship:

Jaida Beaudin-Herney, First Nations University of Canada

First Nations University of Canada

Taryn Acoose, Jaida Beaudin-Herney (IIJ Summer Fellow), Brittany Boschman, Charmaine Ermine, Danna Henderson, Krystal Lewis, Alicia Morrow, Darla Ponace, Mercedes Redman, Shayla Sayer-Brabant, Doris Wesaquate. Instructor: Patricia W. Elliott

University of Regina

Suliman Adam, Kerry Benjoe, Adam Bent, Ethan Butterfield, Jacob Carr, Dylan Earis, Morgan Esperance, Mick Favel, Libby Giesbrecht, Sayda Momtaha Habib, Theresa Kliem, Michelle Lerat, Donovan Maess, Kaitlynn Nordal, Kehinde Olalafe, Heather O’Watch, Julia Peterson, Tuuli Rantasalo, Paige Reimer, Kaitlyn Schropp, Dan Sherven, Penny Smoke, Dawson Thompson, Jasper Watrich. Instructors: Patricia W. Elliott, Trevor Grant, Layton Burton

See the full list of “Broken Promises” series credits and more information about the consortium here.

Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

For tips on this story, please contact the reporters at: iij.tips(at)protonmail.com

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.