The Acadian man remembered for his decades-long fight against the expropriation of land for Kouchibouguac National Park has died.

According to his family, 92-year-old Jackie Vautour passed away after finding out he had liver cancer just days ago.

“A lot people are going to miss him. He’s a hero, he’s a legend,” his son Edmond Vautour said.

“I spoke to him for a few minutes on the phone and he told me he didn’t have long to live.

“He told me that he did all he could,” Edmond said.

In his last conversation with his father, Vautour assured Jackie that he has done enough to make an impact.

Beginning in 1969, about 250 families were displaced from villages on New Brunswick’s eastern shore to create the park, which was authorized under the signature of Jean Chretien, who at the time was minister of Indian affairs and northern development.

Since then, he had been in legal battles with the government, claiming Kouchibouguac is on traditional Indigenous land — not Crown land as defined in the National Parks Act — with title falling to Indigenous communities first.

Vautour received a settlement in 1987 but remained in his cabin in the park, and over the past decades, he had challenged the expropriation in the courts.

In 2015, he filed a lawsuit on his own behalf, and on behalf of a long list of plaintiffs identifying themselves as Indigenous residents of Kouchibouguac territory, as well as hereditary Mi’kmaq Chief Stephen Augustine and several Mi’kmaq people of the area. The lawsuit called for damages for infringing on that title and for the removal of families who once lived in the area.

Get daily National news

Then in 2017, he filed with New Brunswick’s Court of Appeal, to argue a previous ruling that there was no evidence of Métis historically residing in that area.

On Jan. 28, 2021, the court dismissed his appeal in a written decision.

“In a series of legal proceedings involving Jackie Vautour, courts found the expropriations and the creation of the Park were lawful,” the judge wrote.

“It is plain and obvious that a matter that attempts to relitigate that which has been conclusively determined in all levels of court, after a fulsome trial, does not disclose a reasonable cause of action.”

Edmond Vautour said his father was not surprised when his appeal case was rejected, claiming there’s a problem with the justice system.

“He had new evidence to bring into court … and they refused to hear it. It’s pretty bad but he was not surprised at all.”

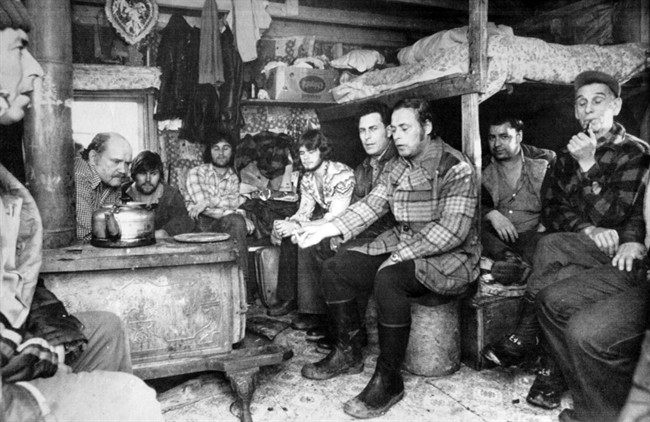

All this time since the expropriation, Jackie Vautour and his wife lived in a small cabin in Kouchibouguac, with no power or water.

“He said that he would die on this land — and he did,” Edmond said.

Although his father has passed, the fight for land title rights is not over.

“My father’s goal was to have the rights of the people, have the people be heard, have the people get back their lands, and to recognize all the suffering the people went through.”

Vautour said Jackie had a good heart.

“He’s a man that never talked badly about anybody. He was always there to help.”

He also said the community has shown kindness after Jackie’s passing, saying that he was a hero.

Alexandre Cédric Doucet, president of the Acadian Society, said Monday that Vautour never gave up on his battle to remain on his family’s land, and he became a symbol that inspired the generations that followed.

“His struggle will forever be etched in our memories, the legacy of a dark part of contemporary Acadian history,” Doucet said in a release.

“Having had the opportunity to meet Jackie a few times, I can personally testify to the strength and determination of this man, who was, in many ways, greater than life.”

Edmond Vautour said he heard suggestions of a petition to change the name of one New Brunswick’s airports to his father’s name.

“I was really surprised to hear that. … His name could never be forgotten for all the rights he stood up for.”

Edmond said he is committed to continuing his father’s legacy and has been especially involved in the last five years.

“Before he passed, he wanted to make sure I was going to continue if I wanted — and I said yes.”

— With files from The Canadian Press.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.