TORONTO – Have you ever wondered why our galaxy is called the Milky Way?

Thousands of years ago the ancient Greeks looked up at the mass of stars that stretched across our sky and, believing it looked like flowing milk across the darkness, called it galaxies kuklos, meaning the “milky circle.” Later the Romans called it via lactea, meaning the “milky road.”

However, look up on a given night and, if you’re like two-thirds of the population, you’ll wonder just what it was those Greeks and Romans were looking at.

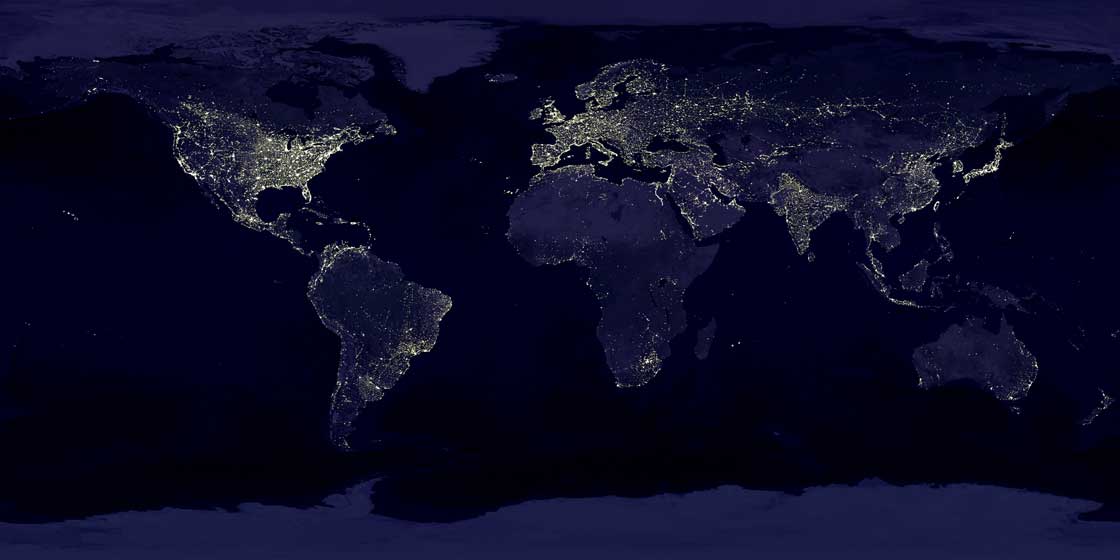

The reason we don’t see the stars is due to light pollution. And you have Thomas Edison and his popularization of the handy electric light bulb to thank for that.

The light bulb has not only led to longer working hours, but also has changed the black sky of night to one with a dull orange glow, devoid of stars.

“There was an earthquake in the ’90s in the Los Angeles area and that knocked out the power and the big thing about that one was that there were many people who saw the Milky Way for the first time… And some people thought that this weird thing in the sky might have caused the earthquake,” said Scott Kardel, Managing Director of the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) based in Tuscon, Arizona.

Light may have its place, but what concerns many astronomers and scientists is exactly how that lighting is being used.

“Light pollution can be light trespass, glare, reducing people’s ability to see or even sky glow, which results in a light dome over a certain area,” said Robert Dick, Chair of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Light Pollution Abatement Committee (RASC). “It lights up the countryside to the detriment of wildlife.”

And the consequences are far-reaching.

Many studies have shown that light pollution has effects on both humans and animals. From sleepless nights to depression in humans to driving off species from their natural environment, the effects have been seen worldwide.

“Beyond the impact to the night sky, many forms of light pollution impact the environment in a variety of ways,” said Kardel. “In terms of the natural world, there are significant impacts just from light at night to insects to migratory birds that fly at night, both of which can be thrown off in terms of navigation. When there are tall illuminated structures, birds will actually fly directly into them at night. But when those lights are turned off, the collisions go dramatically downward.”

Another affect has been observed on sea turtles. Several studies have found that newly-hatched sea turtles use brightness cues — specifically the reflectivity of the water — as a way to orient themselves to the safety of the ocean. But lighting near beaches can confuse the newborns, ultimately leading to their death. Rather than head toward the ocean, they may head toward parking lots or buildings.

“Eliminating light pollution is important because it’s a type of pollution that changes the environment,” said Dick. “The natural environment is one that all lifeforms have adapted to… Once you change that environment and by lighting up the night, you fundamentally change that environment.”

Light pollution linked to increased cancer risk

Not all light has the same effect on humans.

The one that causes the most concern is blue light. Our eyes have something called instrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglian cells. The cells are sensitive to blue light and are believed to be connected to our circadian rhythm, which helps regulate our cycles of day and night. Blue means day, which tells the brain that that’s when we’re supposed to stay up. But, with the advent of electric light, our detectors get confused, never resting, always with some low-level of light seeping in through the night.

A 1999 health study on nurses found that they had a 60 per cent greater chance of developing breast cancer. Why so high? They work night shifts, when the body should be sleeping.

“If you’re on shift work, you’re up all night, and not only that, but your eyes are bathed by the white fluorescent light of a hospital corridor and your melatonin doesn’t get released either, because these twilight detectors keep telling your brain, ‘No, no you can’t go to sleep yet because it’s still daytime.’ So some of these hormones combat the incipient cancer cells. And so they just didn’t have the benefit of the natural mechanism in their body to fight cancer.”

However, Julia Knight, a professor at University of Toronto and a scientist at the Lunenfeld Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto said, “Some work shows that light may actually affect your cell division, not necessarily through melatonin.”

Knight also cautioned against being afraid of moderate lighting in your home, such as that from an alarm clock.

“Humans actually need a high level of light before you see the high level of melatonin suppressed… That’s why people worry about people working shift work.”

“It’s not yet a slam dunk,” acknowledged Dick. “But there’s considerable circumstantial evidence that the blue component in white light at night that you see more and more of is carcinogenic.”

Adapting our way of night life

The IDA is seeking ways to further educate the public, including towns and cities around the world. There are currently two chapters in Canada: one in Alberta and one in Quebec.

Though the IDA was started by two astronomers 25 years ago with the idea of trying to take back the night for stargazing, it has since developed into a worldwide organization aimed at promoting better lighting options for the benefit of wildlife and human health.

However, both Dick and Kardel noted that many municipalities are reluctant to change lighting fixtures due to the persistent belief that lighting decreases crime.

“Putting up light doesn’t decrease crime. It may displace it temporarily,” Dick said.

“Almost two years ago there was a power outage in San Diego that was about eight hours,” said Kardel. “The interesting thing was that there was no bump in crime during the blackout. None.”

Billboard lighting, car dealerships, and lighting that travels up rather than down to its intended source also troubles both the IDA and the RASC. They encourage municipalities to use more “effective” lighting. That may mean full cut-off light fixtures which reduce glare and direct lights to the area they are meant to illuminate or lights that aren’t unnecessarily bright.

Several communities across Canada have lighting bylaws. Richmond Hill, Ont. was the first to put one in place, largely due to the location of the David Dunlap Observatory. But many other communities have followed suit, including Mississippi Mills, Ont., Banff, Alta., Hanwell, N.B., and Saanich, B.C. Calgary has recently moved ahead with its own plans to curb light pollution.

There are also roughly 14 dark-sky preserves across the country, including Torrance Barrens, Ont., the first of its kind in Canada and Jasper National Park, Alta., Grasslands National Park, Sask., Kejimkujik National Park, N.S., as well as Fundy National Park, N.B.

But there are ways that homeowners can do their part. Not only will they cut down on unnecessary lighting, but it will help their pocketbooks as well, says Kardel.

“The first thing to do is, for any lights that you have control of, to look at those lights and see if they’re really on only when they need to be on, if they’re shining where they need to shine and only in the amount they need to be,” he said.

Until cities put into place more effective lighting, the flowing milk of of the starry night sky will be left to dark, unpopulated countrysides. Or we can all wait for another blackout.

For more information on effective lighting, visit The International Dark-Sky Association.

![This map illustrates the amount of light pollution across Canada and the United States. Bright white indicates extreme lighting due to cities. (P. Cinzano, F. Falchi [University of Padova], C.D. Elvidge [NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder]. Copyright Royal Astronomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the RAS by permission of Blackwell Science.)](https://globalnews.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/na_light_pollution.jpg?quality=85&strip=all&w=720)

Comments