A 20-year fight between CN Rail and the people of Milton, Ont., is about to reach its last stop, and Rita Vogel Post is exhausted. “But we haven’t given up,” she says.

CN began quietly buying up property in Milton through numbered companies more than two decades ago, and in 2000, it announced plans to build what’s called an intermodal terminal — essentially a transfer station where trucks unload and pick up containers with goods bound for the rapidly growing Greater Toronto Area.

“Truthfully, we had no clue what an intermodal terminal is,” Vogel Post says.

But the more she learned, the more worried she got.

READ MORE: Halton municipalities concerned with CN truck-rail hub proposal

CN bills the project as an economic and environmental benefit for the region, reasoning that moving hundreds of containers at a time by rail reduces emissions by getting long haul transport trucks off the road.

That’s true, but most intermodal facilities are built in industrial areas, because while they provide an overall environmental benefit, anyone who lives in the immediate area could be exposed to a wide range of health concerns, including dust, noise and light pollution, as well as carcinogenic diesel exhaust. The Milton project would bring 1,600 truck trips per day, going in and out of the terminal, 365 days a year.

That’s why Vogel Post decided to mount a campaign to fight the project. The graphic designer created pamphlets and spoke at community meetings in opposition to the project.

“It’s a class three industrial facility, you know, the highest emissions of noise, light dust, and particulates. It does not belong beside residents.”

It’s a big concern for Priscilla and Jeff Berton, and their two young children. Their five-year-old son Sebastian suffers from asthma.

“I don’t want to be breathing that in and I don’t want my kids breathing it in,” Priscilla says.

“I feel like they’re putting their company’s interests ahead of our health and the good of our town.”

The Bertons say those health risks contributed to their decision to sell their house and move across town. And there are thousands of residents, a dozen schools, and a hospital located within a kilometre of the proposed site.

Opposition to the project is widespread, both among residents and politicians in the area. But that may not matter. Since the time of Confederation, when railroads were key to connecting the country, oversight has rested exclusively with the federal government, which means CN doesn’t need approval from local governments.

Get daily National news

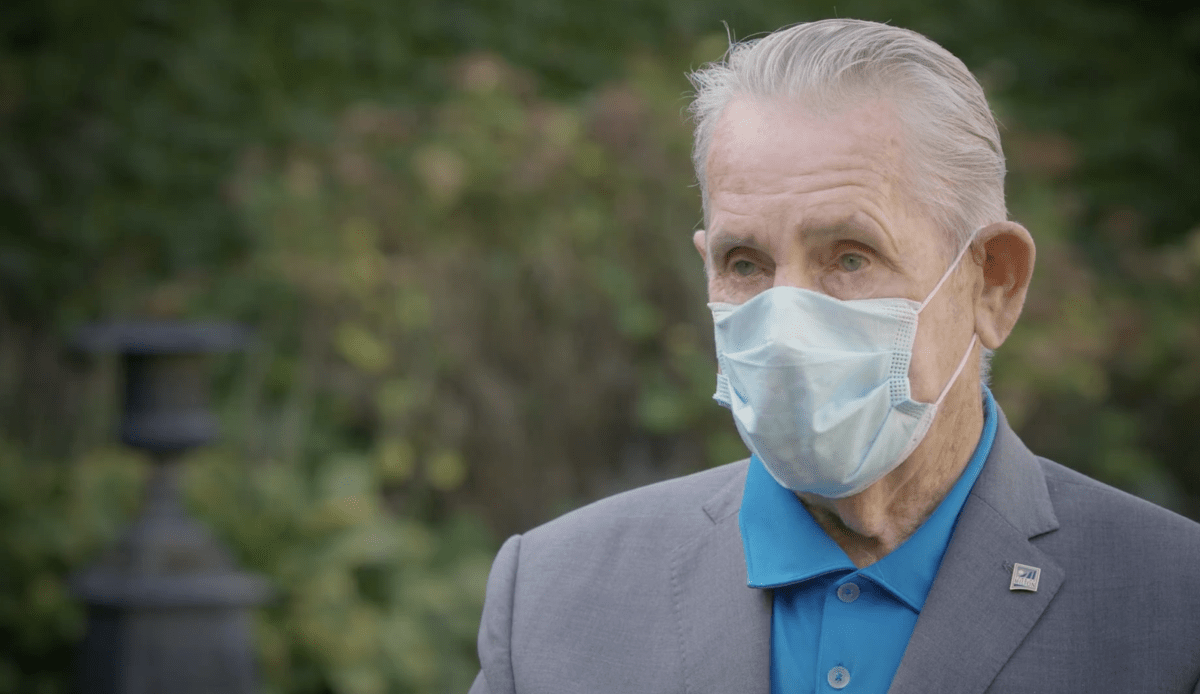

“People have the right to be concerned about what those emissions, those diesel emissions, can do,” says Greg Gormick, a transportation analyst and former CN intermodal expert.

Gormick has a rich family history in railroading going back four generations, and worked for CN when it first proposed the project in 2000.

“It’s like a family,” he says, getting emotional. But his relationship with CN has turned into a family feud. While he supports the idea of intermodal facilities, he says there are better locations than the one CN is proposing in Milton.

“It’s a great idea, I fully support it. There’s just one problem with Milton: it’s the wrong place. It shouldn’t be there,” he says.

The health concerns were backed up by an independent review panel that was appointed by the federal environment minister to analyze CN’s proposal.

In January this year, the panel released a 400-page report, finding that “most of the adverse environmental effects … are likely to occur whether or not the Project proceeds because the lands have been designated for future development.”

But the panel also concluded the terminal “is likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects on air quality and on human health as it relates to air quality.”

It noted that three contaminants, in particular, would exceed air quality standards: Benzene, by 128 per cent, PM10, by 112 per cent, and Benzo(a)pyrene, by a whopping 2,600 per cent.

These are known carcinogens, and Health Canada found “CN had not adequately assessed the health risks from diesel exhaust,” and recommended the corporation “reduce emissions of non-threshold contaminants associated with diesel exhaust.”

That is enough for Milton’s Mayor Good Krantz to oppose the project.

“As far as I’m concerned, there is no negotiations or there is no compromise with the people’s health,” he says.

Krantz knows his constituents pretty well — first elected in 1980, he is Canada’s longest-serving mayor.

In addition to the health concerns, Krantz objects to what he calls CN’s heavy-handed approach.

“Was CN coming to the table and asking if they could do this? No, they weren’t. They were telling us.”

Milton is one of Canada’s youngest and fastest-growing towns, and Krantz says CN’s plan blows apart a long term development plan to accommodate that growth with new home construction, as well as schools and other infrastructure.

“Some of the closest residents will be probably within yards, metres of this facility. And there’s probably going to be at least 10,000 people that would be immediately affected.”

CN declined requests for an interview, but in an emailed statement, the company noted the review panel found “CN’s criteria for site selection were reasonable,” that “the proposed site could support an intermodal terminal,” and that “CN has identified and considered the effects of alternative means of carrying out the Project, including alternative Project locations.”

The opposition is widespread, not only in Milton, but across several municipalities across the region. Even Milton’s Liberal MP, Adam van Koeverden, is against it.

“The people that I talk to at the doors here in Milton, over the course of the last couple of years, they’ve been loud and clear — very, very clear — that CN Terminal just doesn’t have a welcome home here in Milton.”

But all that opposition won’t matter if the federal government approves the project.

The rules governing rail companies are as old as Canada.

The Constitution Act, 1867, ensured railways were the domain of the federal government, at a time when their ability to build and connect the country was essential to the economy.

The result today is that while most industries require a community’s approval to build, CN’s fate falls to the feds.

Rita Vogel Post is aware that her objections might sound like a case of “not in my backyard” syndrome. She insists she is not against intermodal terminals in general, but for her, the risks associated with this one are too high.

“We’re not against inter-modal. But let’s be responsible with where we’re placing it.”

Gormick agrees, saying that if CN gets approval for this project, warts and all, it could do the same thing in any community across Canada.

“There are all these concerns, and I just feel that CN is, pardon the expression, railroading this one through.”

Comments