India’s coronavirus caseload surpassed 4 million on Saturday, deepening misery in the country’s vast hinterlands, where surges have crippled the underfunded health care system.

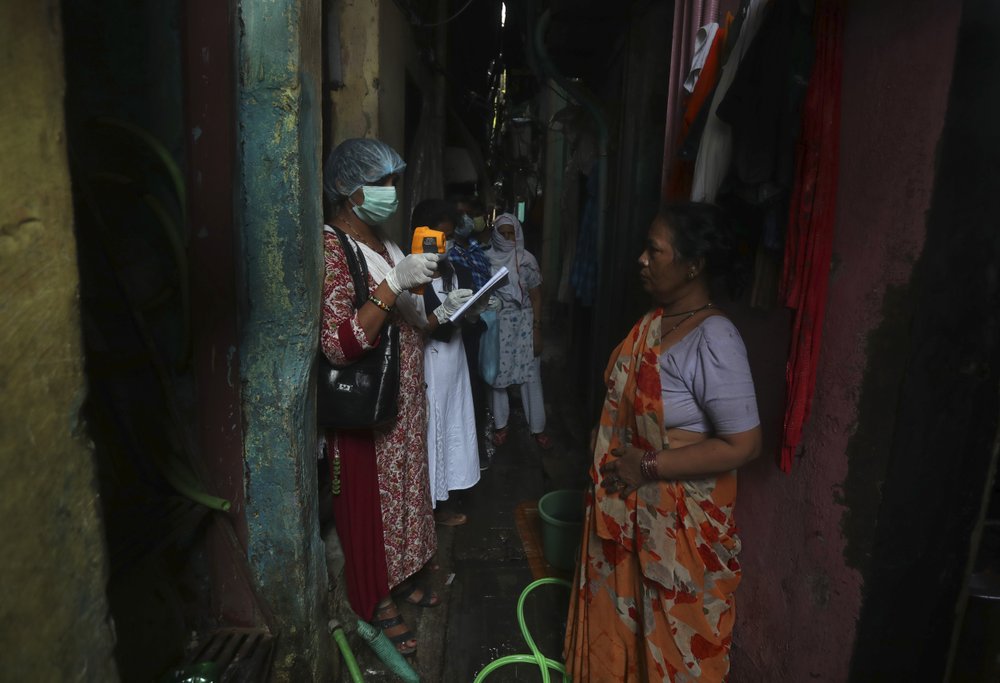

Initially, the virus ravaged India’s sprawling and densely populated cities. It has since stretched to almost every state, spreading through villages and small towns.

With a population of nearly 1.4 billion, India’s massive caseload isn’t surprising experts. The country’s delayed response to the virus forced the government to implement a strict lockdown in late March. For more than two months, the economy remained shuttered, buying time for health workers to prepare for the worst.

But with the cost of the restrictions also rising, authorities saw no choice but to reopen businesses and everyday activities.

Most of India’s cases are in western Maharashtra state and the four southern states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka. But new surges are popping up elsewhere.

Get weekly health news

The 86,432 cases added in the past 24 hours pushed India’s total to 4,023,179. Brazil has confirmed 4,091,801 infections, while the U.S. has had 6,200,186 cases, according to Johns Hopkins University.

India’s Health Ministry on Saturday also reported 1,089 deaths for a total of 69,561.

Even as testing in India has increased to over a million a day, a growing reliance on screening for antigens or viral proteins is creating more problems. These tests are cheaper and yield faster results but aren’t as accurate. The danger is that the tests may falsely clear many who are infected with the virus.

In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state with a limited health care system, the situation is already grim. With a total 253,175 cases and 3,762 deaths, the heartland state is staring at an inevitable surge and with the shortage of hospital beds and other health infrastructure.

Sujata Prakash, a nurse in the state capital, Lucknow, recently tested positive for the coronavirus. But the hospital ward where she worked diligently refused her admission because there was no empty bed. She waited for over 24 hours outside the surgical ward, sitting on patients’ chairs, before she was allotted one.

“The government can shower flower petals on the hospitals in the name of corona warriors, but can’t the administration provide a bed when the same warrior needs one?” said Prakash’s husband, Vivek Kumar.

Others haven’t been so lucky.

When journalist Amrit Mohan Dubey fell sick this past week, his friends called the local administration for an ambulance. It arrived two hours late and by the time Dubey was taken to the hospital, he died.

“Had the ambulance reached in time, we could have saved Amrit,” said Zafar Irshad, a colleague of the journalist.

In rural Maharashtra, the worst-affected state with 863,062 cases and 25,964 deaths, doctors said measures like wearing masks and washing hands had now largely been abandoned.

“There is a behavioral fatigue now setting in,” said Dr. S.P. Kalantri, the director of a hospital in the village of Sevagram.

He said that the past few weeks had driven home the point that the virus had moved from India’s cities to its villages.

“The worst is yet to come,” said Kalantri. “There is no light at the end of the tunnel.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.