Hundreds of flights have taken off and landed at Canadian airports with passengers who were either confirmed positive or suspected of having COVID-19 since the start of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

While the majority of these flights occurred in March, before border restrictions were implemented, data obtained by Global News shows there has been an uptick in suspected cases on board flights in recent weeks compared to April and May, when the number of people flying was at its lowest.

This increase has public health experts and the union that represents thousands of flight attendants in Canada urging the government and airlines to remain vigilant in maintaining, even expanding, safety measures.

“Long before there was community spread, COVID-19 was coming into the country on airplanes,” said Troy Winters, senior health and safety officer at the Canadian Union of Public Employees.

“We were quite concerned, right from the get go.”

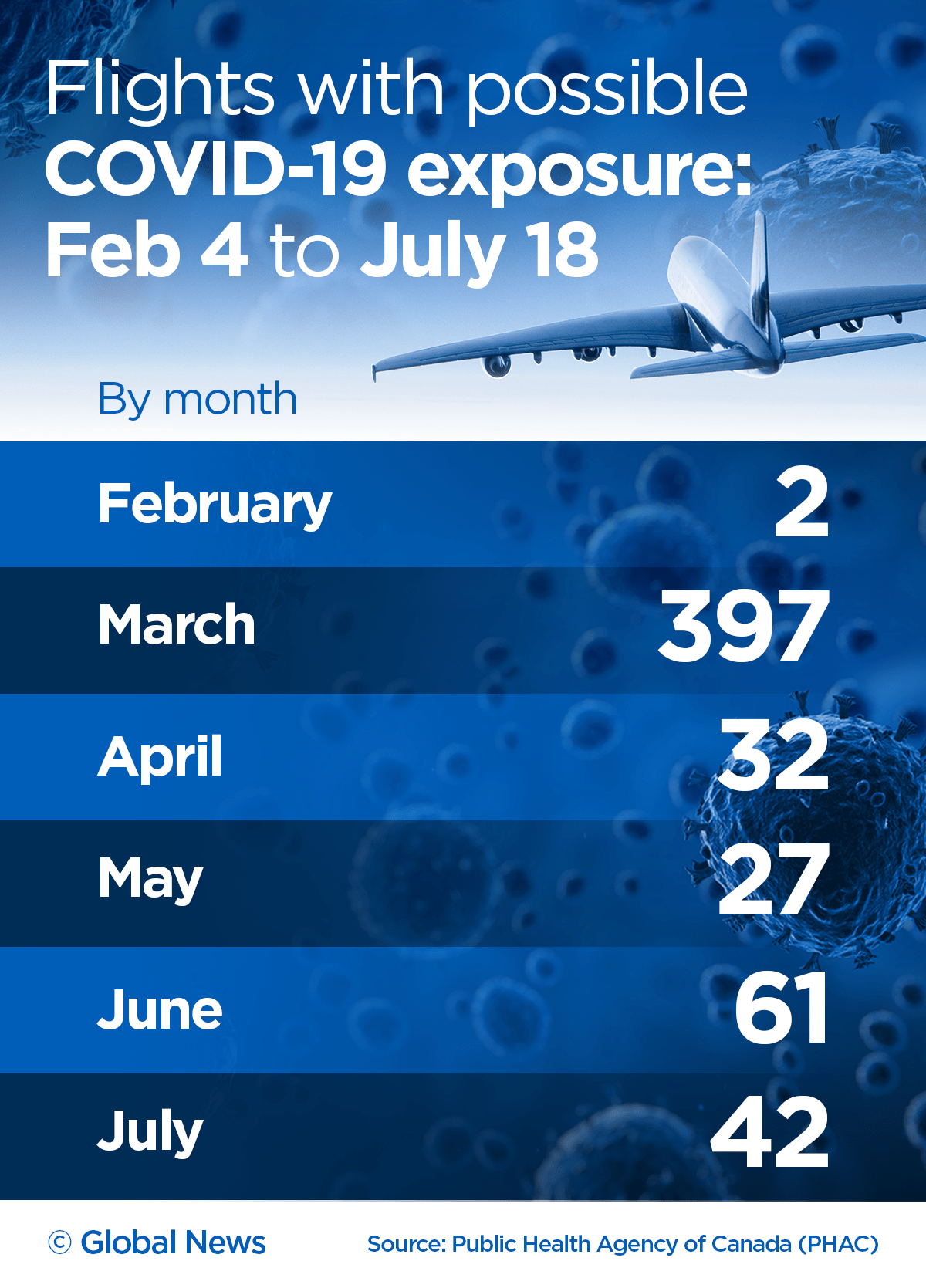

In total, 561 flights with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 arrived at or departed from Canadian airports between Feb. 4 and July 18, according to data provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Of these, 200 flights were listed as domestic and 361 were international.

More than two-thirds of possible exposures — 397 in total — occurred in March. There were then 32 flights with possible exposures in April, 27 in May, 61 in June and 42 in the first two weeks of July.

Only two flights — both departing from Toronto — were listed in February.

In terms of flights arriving from international locations, London, U.K. had the highest number of possible exposures with 41 flights in total. Frankfurt had 19 possible exposures, Cancun 18, while New York and Newark, NJ combined for 16 flights.

Domestically, Toronto had the highest number of departing flights with possible exposures at 97, Vancouver had 51, Calgary 35 and Montreal 23.

The data, however, is “not exhaustive,” so there could be other cases of possible exposures the government is not aware of.

How safe is flying?

Get daily National news

Airlines and travel groups — including Air Canada’s CEO — have pressed the government to open up the border and ease certain travel restrictions, citing the economic harm to the tourism industry caused by the novel coronavirus pandemic.

But public health experts and government officials have pushed back against these ideas, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who in late June warned of the possible risks of increasing travel too soon.

And while governments and public health experts seem to agree on the importance of maintaining border restrictions, there are still questions about how safe the actual act of flying is from the public and government health officials.

When Air Canada and WestJet announced in late June that they’d resume selling the middle seat on flights, passengers and airline personnel expressed concern.

Canada’s chief public health officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, suggested airlines should consider a passengers’ underlying health conditions and other circumstances when assigning seats, adding that physical distancing of two metres should be maintained whenever possible.

But as recently as Monday, Transport Minister Marc Garneau remarked on the relative safety of travelling by air.

He said there have been no documented cases of COVID-19 transmission linked directly to air travel and that measures currently in place to slow the spread of the virus have been effective.

“With everything that is being done on aircraft, with respect to cleaning between flights, with respect to the air flow system, with the way the air flows on the aircraft, there is no evidence, there is not a case yet of somebody actually picking up the virus on board the aircraft,” Garneau said during an interview with CBC.

Global News requested information from Garneau’s office regarding government efforts to track the risk of contracting COVID-19 onboard a plane. No information was provided and the request was referred to Health Canada.

Meanwhile, Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease specialist at Toronto General Hospital, said the best scientific evidence available doesn’t support claims that air travel is risky.

He said air filtration and preventative measures — such as mandating that masks be worn at all times and providing hand sanitizer to passengers — make transmission of the virus unlikely when flying. He also said possible exposures would likely be limited to people sitting beside, in front or behind an infected person.

“If the question is, can you get COVID-19 on an airplane, the answer is, yes, of course you can. But I think the risk is much smaller than what people think,” Bogoch said.

Mandatory vs. voluntary requirements

For Winters, the number one thing he’d like to see from the government is stricter requirements on what airlines must do to keep employees safe.

So far, he said, most of the measures put in place by the airlines to protect workers have been voluntary, such as limiting meal service, restricting use of front washrooms for staff only, using private transportation to and from airports, and wearing N95-certified masks while onboard.

Winters would like to see these precautions and any other best practices made mandatory.

“We’ve been very disappointed with the level of government recommendations,” he said. “The government has been very hands off.”

For others, however, the main issue is making sure existing protocols meant to stop the spread of the virus are maintained once people arrive at their final destinations.

Dr. Craig Jenne, an infectious disease and microbiology expert at the University of Calgary, said enforcing the 14-day quarantine for anyone who enters Canada is critical to limiting the spread of COVID-19.

He also said public health officials and governments must be wary about allowing travellers to enter Canada, especially travellers from countries that haven’t done as well with testing.

“There’s a bit of a worry with relying on real-time data for a disease that has a 10- to 14-day lagtime,” Jenne said.

“Numbers we see today reflect the transmission events that happened almost two weeks ago. So we do have to be particularly cautious.”

Still, there are some measures Jenne thinks could potentially reduce the length of quarantines, such as testing everyone at the border and then testing them again several days later before deciding whether to lift the quarantine.

This, he said, could reduce the duration of quarantines from 14 days to as little as four or five days.

However, absent this type of widespread, repeat testing for all travellers who enter Canada, longer isolations are still necessary because the type of screening done for airline passengers — including temperature checks and asking about any signs of sickness — are largely ineffective.

“We have to be very cautious of these tests that are looking for symptoms or conditions of the virus and not looking for the actual presence of the virus in travellers,” he said.

Global News asked the government what steps it takes after it lists a flight as having had a possible COVID-19 exposure, such as contact tracing, testing and notifying passengers.

The government did not answer these questions.

— With files from Heather Yourex-West.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.