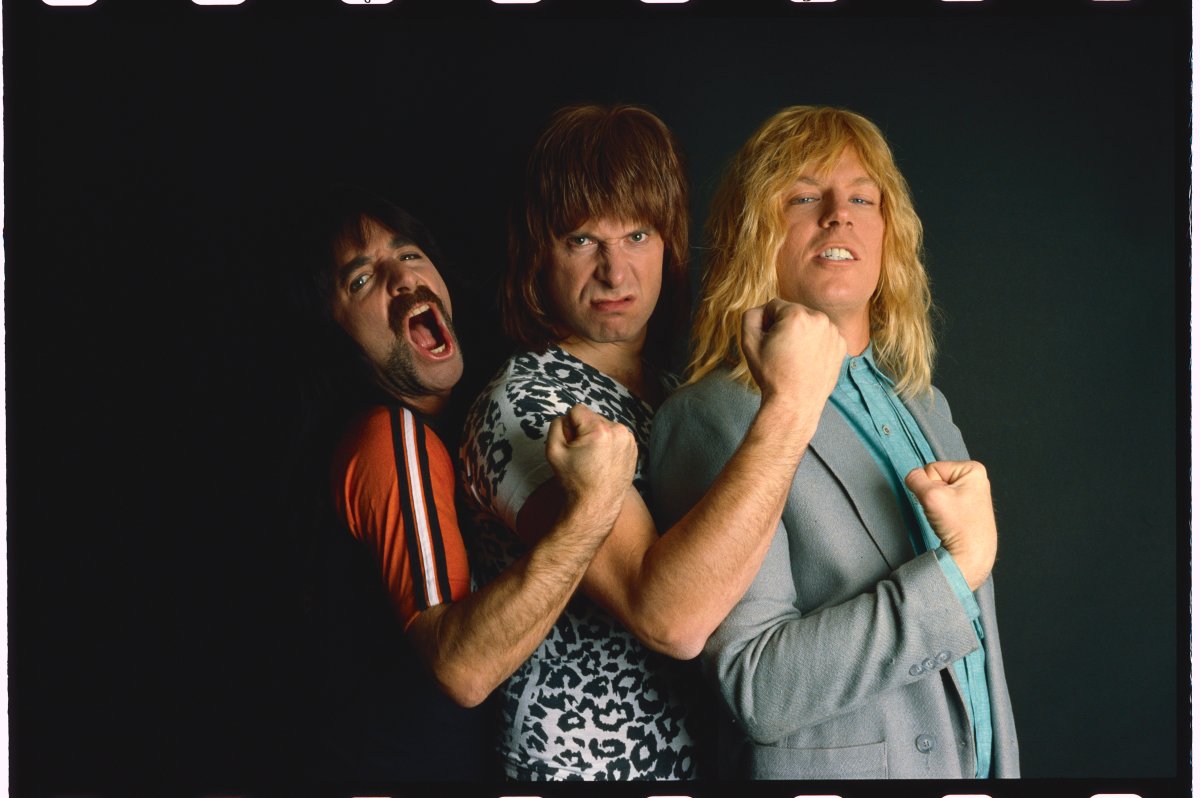

One of the most iconic music-related cinema moments has Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel demonstrating how his custom Marshall amplifier is equipped with a volume control knob that goes a little higher than normal.

Ear-splitting volume has been inextricably associated with rock ever since the genre developed in the 1950s, but don’t give it all the credit/blame. People have been screaming for musicians to turn it down for centuries.

At first, the volume at which humans could perform music was restricted. What kind of lung power did you have when it came to singing? How hard could you hit, pluck, or blow into something? And how well would that physical force transform into sound pressure levels?

Anything could be made louder by having more people do the same thing simultaneously. If we have to guess, ancient drum circles, the kind used for religious rituals or preparing for battle, were once the loudest form of music on the planet. The more drummers you had, the greater the volume.

WATCH BELOW: Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel demonstrates how his custom Marshall amplifier goes to 11

And then there was the role of architecture. Amphitheatres, cathedrals, and concert halls were constructed as natural amplifiers so actors, singers, and priests could be heard throughout the structure. The Romans discovered that if you draped a tent over their amptheatres, the sound was kept in.

Later, all the great opera houses were built to make whatever came from the stage and the orchestra pit seem louder.

The first instance of someone complaining that the band was too loud may have been in the audience for the 1813 premiere of Beethoven’s new work, Wellington’s Victoria, a not-very-good celebration of the Duke of Wellington’s win over Joseph Bonaparte in Spain earlier in the year.

Yes, Beethoven was going deaf, but that wasn’t the reason for his demand for maximum volume. His goal was to summon the sensation of being in the midst of a great military battle, which is why Wellingtons Sieg oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria Op. 91 was arranged for massive numbers of horn instruments as well as a battalion of drummers, along with some actual muskets. Over a hundred musicians were required and the racket they made was immense.

There were no sound level meters to measure the decibels cranked out by Beethoven’s orchestra, but a good guess would be that they generated around 120 dB, equivalent to a modern rock concert.

Get breaking National news

Other composers took up the challenge. As instrument design and construction became more robust (metal instead of wood, trumpets and horns with greater range), the music got louder and louder. Berlioz had a wish for a 400-piece orchestra. He never got there, but his Symphonie Fantastique employed two giant church bells, which is one more than what AC/DC would use.

But what of the solitary singer performing for an audience? Again, the only solution was big lungs. In the days of Vaudeville — the era before microphones and amplifiers — singers known as “belters” developed techniques that allowed their voice to be projected to the very back rows of the theatre.

When jazz evolved into the big band era, orchestras needed at least a dozen members (and often more) to be heard throughout the ballrooms and above the noise of the crowd. Maintaining such an operation was already extremely expensive when World War II created a shortage of qualified players, hastening the end of the big bands.

READ MORE: Post Malone announces Nirvana tribute fundraiser for COVID-19 relief

- ‘Alarming trend’ of more international students claiming asylum: minister

- Justin Trudeau headed to UN Summit of the Future amid international instability

- Canadian government’s satellite deal has Tories calling for Elon Musk involvement

- Activists call for Boogie the monkey to be removed from Ontario roadside zoo

The ensembles that followed — bebop jazz groups and R&B outfits — were smaller and comparatively quieter. Horns were the loudest instrument and had to be balanced with whatever volume could be wrung out of a piano or a stand-up bass. Mics, amplifiers, and electric guitars were in widespread use by the late 1940s, but were puny in terms of output. For the most part, if you wanted to be louder, you just had to play and sing harder.

When rock’n’roll appeared on the scene, things got dire quickly. When Radio DJ Alan Freed held his Moondog Coronation Ball on March 21, 1952 — probably the first-ever rock concert — there was nothing resembling sound reinforcement. The performers had their on-stage amps and that was it. PA system? What’s that?

The first concert sound systems were nothing more than a combination mixer/amp powering a couple of speaker columns on either side of the stage, each containing maybe a couple of 12-inch speakers each. When the Beatles played their famous Shea Stadium show in August 1965, they set up on a small stage with a couple of 100-watt Vox amps. Everything else was pumped through the stadium’s public address system, consisting of a series of 175-watt amps powering the same speakers used by the announcer to tell the crowd who was coming up to bat.

Fortunately, a group of sound enthusiasts working on the problem. In 1963, the Beach Boys contacted Sunn Electronics and asked the company to design what became the first large full-scale sound system for use in a rock concert environment. Then Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass contacted Harry McCune Sound Systems to build something for a 1965 tour.

Manufacturers weren’t crazy about this focus on volume. Some even warned musicians that turning up their gear too loud would void the warranties. But as rock grew bigger and tours and festivals grew more numerous (think Woodstock), a lot of R&D went into technology that provided loud, clear sound. This audio arms race was on.

READ MORE: Eminem donates ‘mom’s spaghetti’ to Detroit hospital workers fighting COVID-19

Pink Floyd might have been the first band to achieve sound pressure level notoriety. In 1971, they were presented with a bill for 300 dead fish that were allegedly vibrated to death when they played at 95 decibels during a show at London’s Crystal Palace. Then came Deep Purple who was measured playing at 117 decibels at London’s Rainbow Theatre in 1972. The Grateful Dead blew everyone away in 1973 with their 75-ton, three-storey, 100-feet-wide Wall of Sound rig, featuring 586 JBL and 50 Electro-Voice tweeters, powered by McIntosh tube amps pumping out 26,000 watts. It was insane for its day.

Three years later, The Who were measured at 120 dB from 100 feet away during a gig, a feat that was logged in the Guinness Book of World Records. That mark stood until the mental band Manowar reached 129.5 dB in 1984, only to be eclipsed by Motorhead with an even 130 dB later that year. In 1996, the electronic band Leftfield reportedly reached an insane 137 dB at Brixton Academy, apparently causing some members of the audience to pass out. That’s about the same level as a 747 at takeoff.

Manowar would have none of that, cranking things up to 139 dB during soundcheck at the Magic Circle Festival in Germany. And as far as anyone can tell, a Swedish band called Sleazy Joe reached 143.2 dB during a gig in Hässleholm. That’s almost equivalent to standing 25 metres away from a jet fighter at full takeoff thrust and a level that causes immediate damage to all parts of the ear, not to mention serious pain.

At this point, we’ve seemed to reach the limit of musical amplification. We’ve long passed anything resembling overkill. You kids keep your music down, okay?

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

Comments