Long pipeline routes that cross provincial and Indigenous territorial boundaries are part of the reason that Canada is a more difficult place than the U.S. to build major energy projects, according to American analysts.

The comments came in the wake of a decision by Teck Resources Ltd. on the weekend to cancel its proposed $20.6-billion Frontier oilsands mine.

Adequate pipeline access from the Alberta oilsands to export markets was one of the issues Teck said it must solve — along with oil price and bringing in a partner — in order to proceed to construction of the mine.

“We’re talking about some pretty long-haul pipe that touches a lot of areas, a lot of communities, a lot of different Indigenous groups and I think that’s where it starts to get really messy, really quickly,” said Jennifer Rowland, a senior analyst in St. Louis, Mo., for Edward Jones.

“And that, I think, is part of the bigger challenge in Canada than in the U.S.”

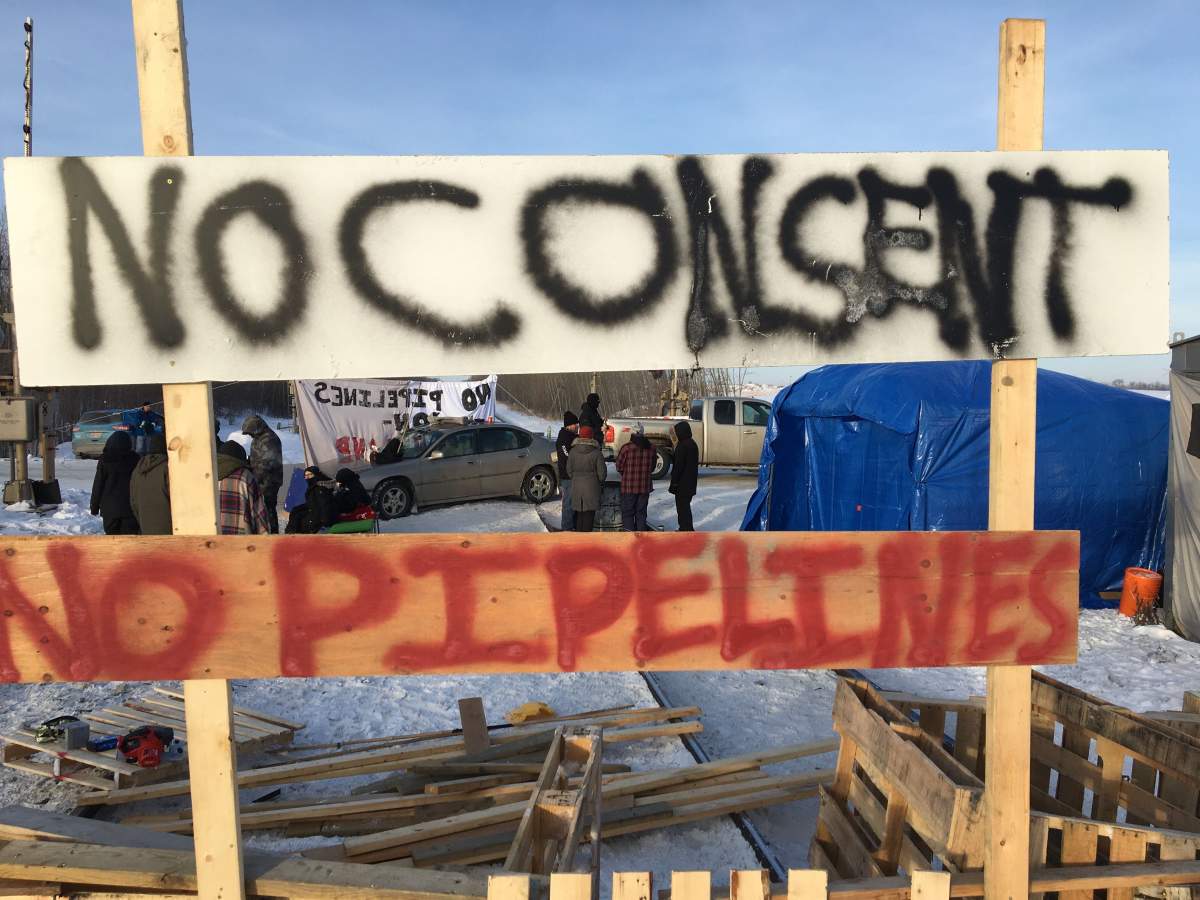

Indigenous and environmental opposition in the U.S. to the 1,930-kilometre Dakota Access pipeline resulted in vocal protests and delays in 2016 and 2017, but it was built after law enforcement agencies enforced its regulatory approvals, she said.

The reluctance of Canadian law agencies to provide similar enforcement for approved projects is another competitive disadvantage, she added.

New York-based analyst Phil Skolnick of Eight Capital agreed geography is important, pointing out pipelines needed to bring oil and gas from wells in the fast-growing Permian region of northern Texas to the U.S. Gulf Coast, for instance, can be built entirely inside that state’s borders.

“Alberta’s in an unfortunate position because it’s located in the wrong part of the country… it’s been at the mercy of what the other provinces want,” he said.

“No one’s telling Texas they can’t build pipelines from the Permian.”

Get breaking National news

Pipelines that cross several state borders, however, such as the Keystone XL pipeline between Alberta and the U.S. Midwest, have been delayed by opposition on the U.S. side of the border after easily winning approval on the Canadian side, he said.

On Monday, a partner in the nearly US$1-billion Constitution Pipeline project to bring natural gas from Pennsylvania to New York confirmed it had been abandoned after years of legal regulatory challenges drove the price up from the original US$700 million when it was proposed in 2013.

Opponents fought the pipeline because the Pennsylvania gas would be produced from wells that had been hydraulically fractured or “fracked,” a practice that is banned in New York state.

The decision shows that it’s difficult to build energy projects anywhere in the world these days, said Jack Mintz, president’s fellow at the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary.

But it’s especially hard in Canada, he said.

“In my view, it’s because of a combination of weak federal leadership, a political situation which has gotten out of hand where particular groups are pushing a line [and] maybe there’s an anti-Alberta view that’s colouring it,” he said.

He said there needs to be a “grand bargain” in Canada that sets out how the country can achieve environmental goals without badly injuring its resource-heavy economy.

Meanwhile, in Ottawa, Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson said Tuesday he agrees with Teck CEO Don Lindsay’s call for “much more active collaboration” on the climate file between federal and provincial governments.

“I do think there is an opportunity for conversations about how we can work together to address emissions, to reduce emissions from the oil and gas sector in a manner that actually promotes sustainable economic development for the sector,” he said.

Wilkinson said the fossil fuel sector has to address emissions to meet demands from the international investment community.

–With a file from The Canadian Press’ Mia Rabson

Comments