A famous Egyptian mummy‘s “voice” has been heard for the first time in 3,000 years after researchers recreated the long-dead priest’s vocal cords using modern 3D-printing technology.

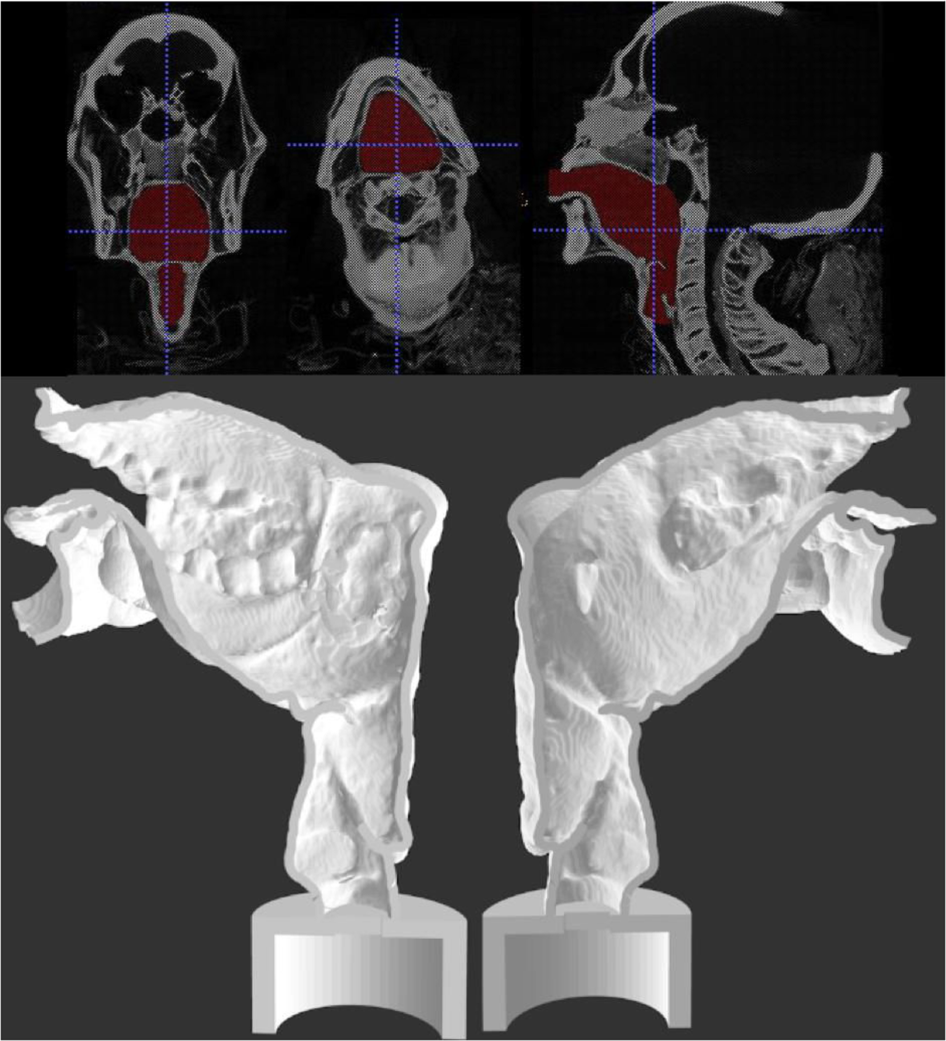

Scientists used three-dimensional scans to map the mummy’s entire vocal tract, then re-created it using a 3D printer. They used an artificial larynx to run air through the synthetic vocal cords, creating a single vowel sound in the dead Egyptian’s voice, according to findings published in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Ehhhhh…” the voice says. It sounds a lot like a groaning mummy from a Hollywood movie.

The voice once belonged to Nesyamun, a priest who lived in Thebes during the tumultuous reign of Rameses XI and died around the age of 50. His mummified body was recovered about 200 years ago and sold to a museum in the United Kingdom, where it was unwrapped and dubbed the Leeds Mummy.

“What we have done is to create the sound of Nesyamun as he is in his sarcophagus,” study co-author David Howard, head of the department of electronic engineering at Royal Holloway, University of London, told The Guardian. “It is not a sound from his speech as such, as he is not actually speaking.”

A person’s voice is shaped by the precise dimensions of his or her vocal tract, according to the study.

“Since the restoration of an exact vocal sound requires the perfect preservation of the soft tissues, this is impossible for individuals whose remains are only skeletal,” the paper says. “The process is only feasible when the relevant soft tissue is reasonably intact, as in the case of … Nesyamun.”

Researchers say the sound is based on the position of Nesyamun’s vocal tract at the moment of his death. The same approach can’t be used to simulate other sounds.

In other words, researchers can’t create sentences in Nesyamun’s voice.

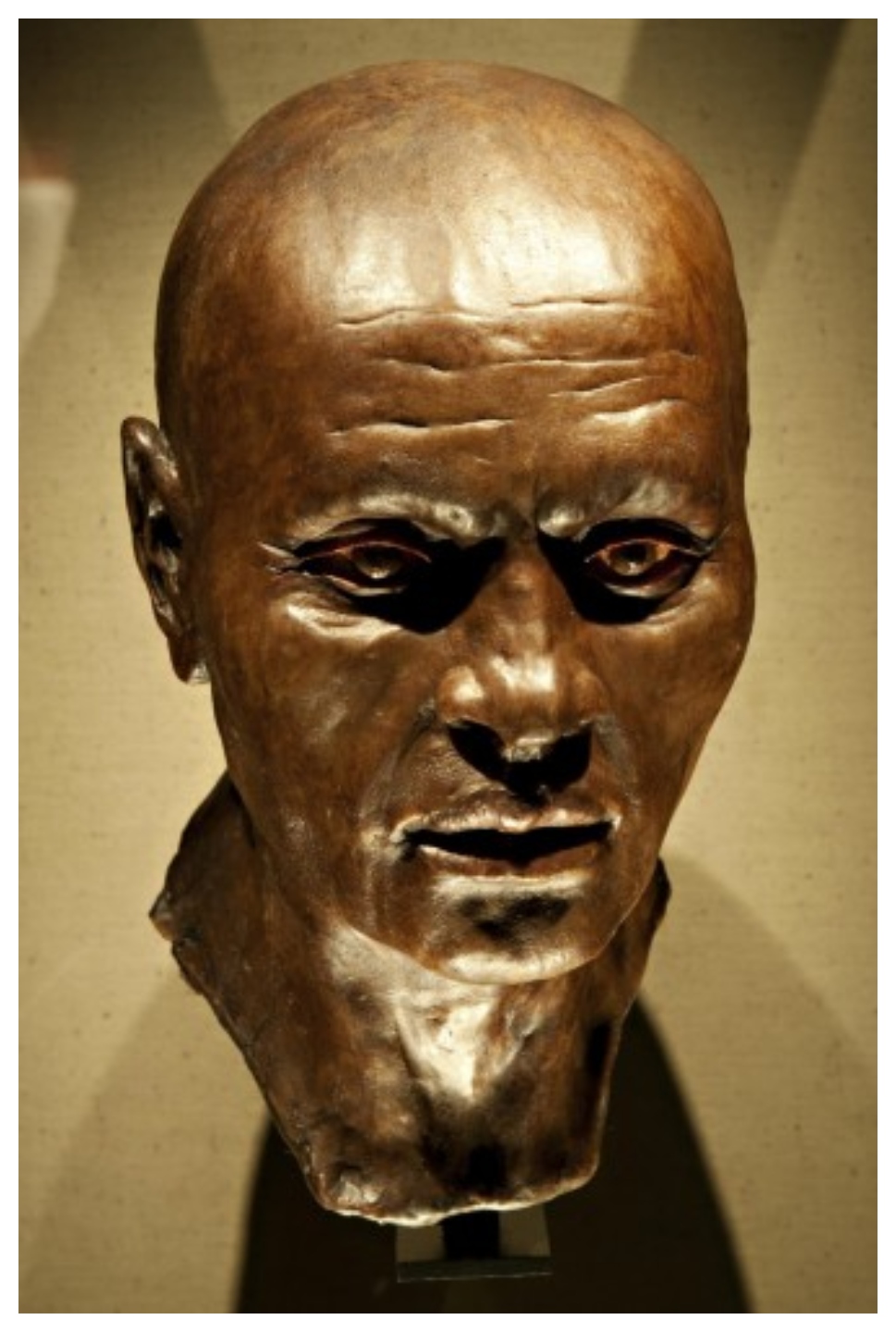

This is just the latest archeological breakthrough involving Nesyamun, whose mummy has been studied in various ways for nearly 200 years. It was unwrapped for a multi-disciplinary investigation in 1828, and was more recently used to create a 3D bust of what Nesyamun would have looked like when he was alive.

There is some debate around the exact cause of Nesyamun’s death. It was once thought that he’d been strangled, but the current theory suggests that he may have died from an allergic reaction to an insect sting, according to the Leeds City Museum.

If the latter theory is right, his last noise might have been a yelp of pain. The exact vowel sound falls where between the vowels in “bed” and “bad,” the paper says.

Nesyamun’s mummy remains part of the collection at the Leeds City Museum, where staff hope this new discovery will open up more opportunities for learning.

The study authors say their work is a proof of concept, and they hope the same approach can be used for other subjects in the future.

Nesyamun was a high-ranking “waab” priest who used his voice for singing and chanting, according to archeology professor Joann Fletcher of the University of York. His voice would have also been important for the afterlife.

“Every Egyptian hoped that after death their soul would be able to speak,” Fletcher told The Guardian. Egyptians believed they’d get a chance to list off all the good deeds they’d done in life, in hopes of convincing the gods that they deserved the best afterlife.

“Only if the gods agreed could the deceased soul pass through into eternity,” Fletcher said. “If they failed the test they died a second, permanent death.”

Nesyamun had actually hoped for his voice to be heard in the afterlife, Fletcher told BBC News in a separate interview.

“It’s actually written on his coffin. It was what he wanted,” she said.

“In a way, we’ve managed to make that wish come true.”

- Four injured after military horses break loose, stampede in London, U.K.

- Canada refused to repatriate woman from ISIS camp because she can’t be arrested: internal memo

- Russia vetoes UN resolution to prevent nuclear arms race in space

- Why U.S. colleges are turning to police to quell pro-Palestinian student protests

Comments