B.C. Premier John Horgan’s visit to Kitimat’s LNG Canada project is creating strife among Indigenous leaders at the centre of a natural gas pipeline dispute.

Horgan won’t meet with hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en during the trip.

A spokesperson for the premier’s office said Horgan’s schedule was set prior to receiving a request for a meeting from hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en, and that they were trying to set up a phone call.

It’s an offer that’s getting little traction from the hereditary chiefs, who have refused repeated requests to meet with pipeline developer Coastal GasLink — instead demanding a nation-to-nation meeting with the provincial government.

“If he’s up in this part of the province, it really would not be that difficult for him to show some respect to the hereditary chiefs and meet with all of us at the same time.

“The Crown is at risk if duty to consult is not followed. And it is the Crown itself who must meet with us.”

Speaking during a tour of the site for the future LNG export facility, Horgan said Friday that his government has been in consultation for more than 18 months with the Wet’suwet’en, though not over the pipeline.

Get breaking National news

“The message I have for the Wet’suwet’en people is that we’re working diligently to ensure we can have genuine reconciliation,” he said.

“There’s still tensions in the community, and I understand that. But the Wet’suwet’en also need to understand that this project is duly certified, it’s been permitted by all levels of government and the project is proceeding.”

Horgan pointed to a Dec. 31 B.C. Supreme Court injunction that ordered all obstructions to pipeline construction be cleared, repeating contentious comments he made earlier this month that the issue was a matter of “rule of law.”

Interim Green Party Leader Adam Olsen, meanwhile, has scheduled a trip to visit the chiefs in their northern B.C. camps over the weekend.

Olsen, a member of the Tsartlip First Nation in Brentwood Bay, said he was invited by the hereditary chiefs this week and is going as a sign of respect and reconciliation.

He added the “strong language” being used by government and industry during the dispute has him concerned, particularly in the wake of B.C.’s adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“This is the legacy of the colonial government and the approach that’s been taken. This is the legacy of the Indian Act that we see playing out and it’s played out time and again in the country,” he said.

“I was very deeply understanding of the fact that some of these issues that have been ongoing are going to get caught in this transition, and that it’s taking time for us to get to where we’re at and it’s going to take time for us to get to where we need to be.”

Olsen wouldn’t comment on whether Horgan should meet with the Wet’suwet’en chiefs while he’s visiting the north, only saying he’s hopeful all sides can reach a non-violent solution.

Horgan said the province has no role in directing the actions of the RCMP, who have set up an “access control checkpoint” at the 270kilometre mark of an access road to a key pipeline worksite, an action some observers have taken to be a prelude to enforcing the injunction.

A police raid to clear a similar protest camp, following a similar injunction in January 2019, resulted in 14 arrests and drew accusations of heavy-handed police tactics, particularly after a report in U.K. newspaper The Guardian alleging RCMP discussed deploying snipers and putting children into social services during that action.

Police have denied that report.

Tensions in the area have been growing as speculation mounts as to when or if police will act to enforce the injunction.

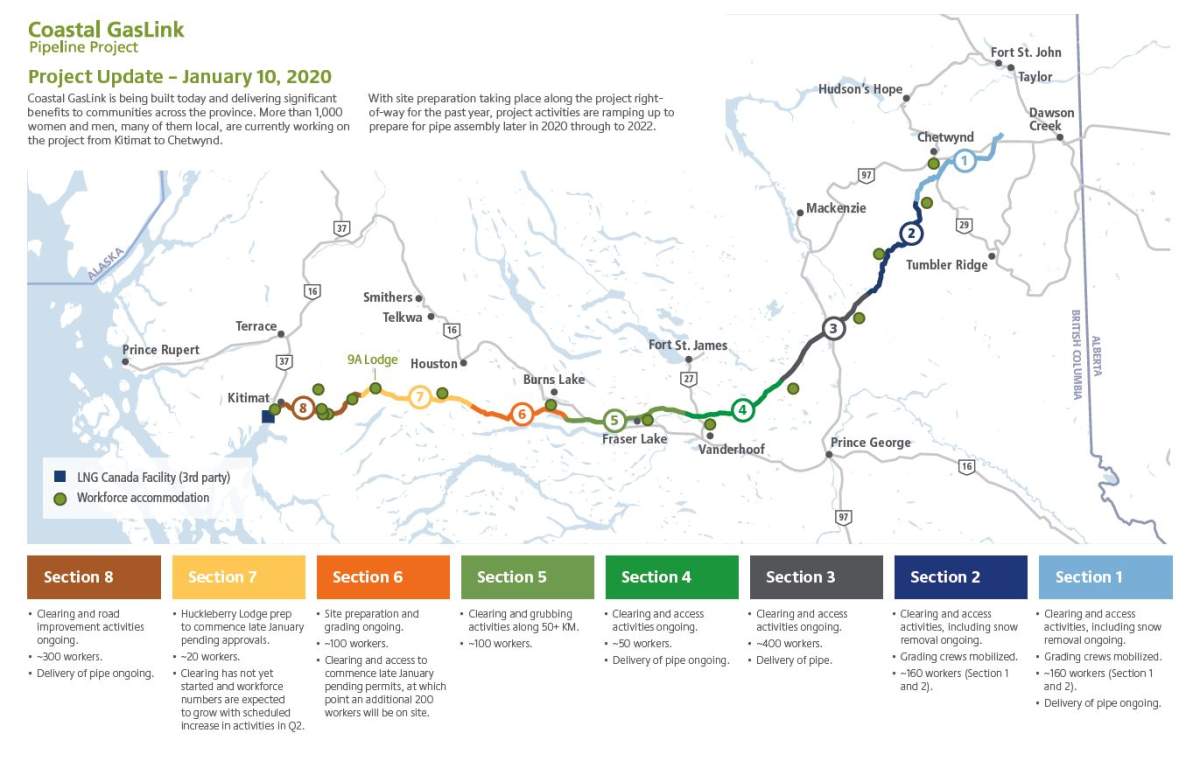

The $6.6-billion project would connect northeastern B.C.’s gas fields with the LNG Canada plant.

It has earned the support of all 20 elected Indigenous councils along the route.

However, the Wet’suwet’en say elected councils only speak for their specific First Nations reserves, and are an artifact of the colonial system.

The Wet’suwet’en have never signed a treaty with the government of Canada or British Columbia, and hereditary chiefs claim the sole authority over land decisions for unceded territories.

- After tragedy, Lapu Lapu victims were victims of ‘snooping’ at hospitals: report

- $10-a-day daycare program paused in order to stabilize, B.C. government says

- Rockslide closes Highway 93 between B.C. and Alberta until at least noon on Thursday

- Tumbler Ridge school portables are for when students, staff ‘are ready’

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.