When Haiti was rocked by an earthquake on Jan. 12, 2010, images of despair and damage struck a chord with people around the world.

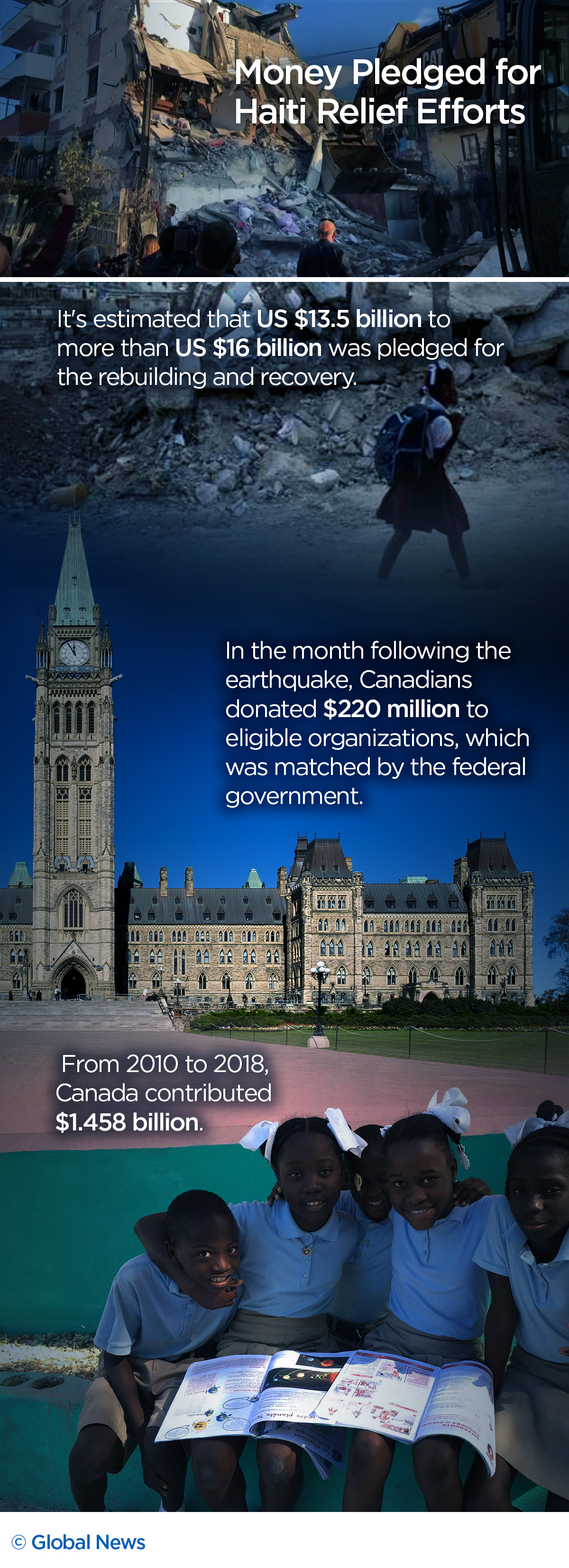

American journalist Jonathan M. Katz has closely analyzed the money pledged and how much was actually disbursed. He reports the global response totalled US$16.3 billion in pledges for rebuilding and recovery efforts. Other estimates, including from the L.A. Times, pin it at US$13.5 billion. In the month following the earthquake, Canadians donated $220 million to eligible organizations, which was matched by the federal government. From 2010 to 2018, Canada contributed $1.458 billion, which does not include the $220 donated by Canadians.

But after such a sizable commitment, seemingly little has changed for many Haitians.

“We’re still living in that same moment in that same time,” Guillano Louis, who lives in Port-au-Prince, tells Global News on the streets of the capital.

In the area of Canaan, a two-hour drive northeast of congested Port-au-Prince, some families still live in tents set up as a temporary measure for displaced residents after the earthquake. A family of seven sleeps in a threadbare tent, without access to running water, electricity or public services such as education. Some of the children were born in these conditions.

With 10 years gone by, there are questions from the international community about the lack of progress.

“The headline should be, ‘We screwed up,’” says Katz, reflecting on the global response.

He explains that the international community didn’t keep its promises.

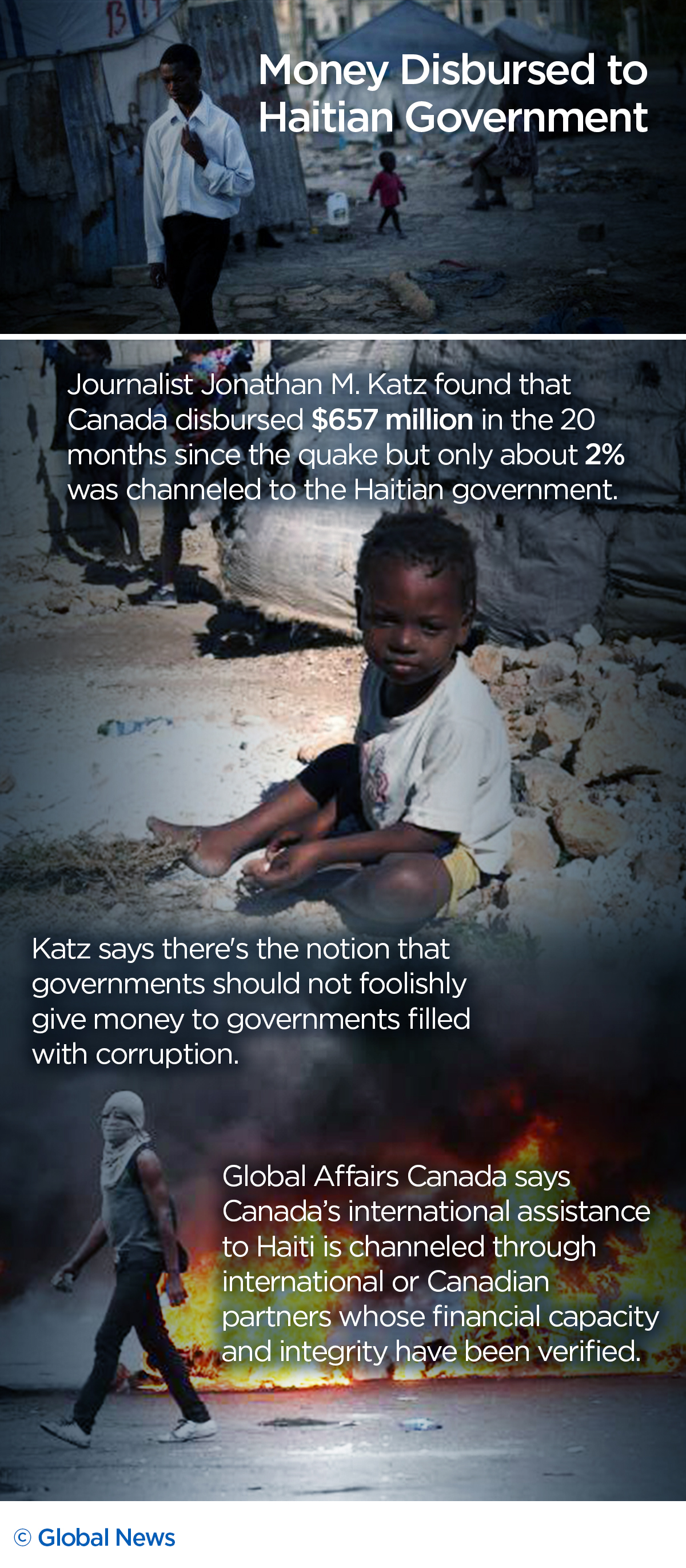

Katz was inside his home in Haiti when it “buckled along with hundreds of thousands of others.” In his book, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster, he claims Canada disbursed $657 million in the 20 months since the quake, but only about two per cent was channelled to the Haitian government.

Global News reached out to Global Affairs Canada for confirmation of the figures provided by Katz. In a statement, the department says it is “unable to confirm this figure, as we are not aware of the methodology that was used to arrive at this amount.”

“Canada’s international assistance to Haiti is channelled through international or Canadian partners whose financial capacity and integrity have been verified,” the statement says.

Katz says there’s the notion that governments should not foolishly give money to countries filled with corruption. The Haitian government is widely accused of corruption, mismanagement and misinformation, right down to the number of people it says died in the earthquake. The government estimates 316,000 people died and 200,000 people were injured, figures many believe to be inflated. The BBC cites a draft report commissioned by the U.S. government that puts the death toll between 46,000 and 85,000. Many news outlets report 220,000 lives were lost.

In Port-au-Prince, many Haitians lament their current situation. A vendor selling patties, who did not want to be identified, told Global News she is fed up with the government’s inaction. She says she never saw any of the food and supplies distributed, and believes the government kept things for itself.

Get daily National news

Louis, who works in security and was in Port-au-Prince at the time of the earthquake, echoes that sentiment. He says the earthquake is still fresh in the minds of Haitians.

“There’s been no real progress,” he said.

He believes the Haitian government is to blame and voiced that “someone needs to say something.”

In a statement released on the 10th anniversary of the earthquake, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse said the government still lacks “the basic infrastructure and services to support the people of our country.”

“The initial flurry of attention received from the international community quickly quieted down, with many of the financial pledges not delivered — causing devastating consequences for our recovery,” he said. “Little of the aid that was received ended up in Haitian hands and much of the money that was so generously given was not spent on the right projects and places.”

Katz says there’s a lot of noise about corruption in places like Haiti, but little of the aid is actually going to Haiti. Often, foreign donors choose to give to NGOs due to fears of corruption by the Haitian government. But some NGOs are also accused of mismanagement.

In 2015, NPR and ProPublica released their findings into the US$500 million raised by the American Red Cross for relief efforts in Haiti. ProPublica’s headline read: “How the Red Cross Raised Half a Billion Dollars for Haiti and Built Six Homes.” According to NPR, their investigation found a number of “poorly managed projects, questionable spending and dubious claims of success.”

Katz explains that foreign aid is “a misnomer.”

“It’s usually not aid and it’s not given to foreign countries,” he said.

Katz says that with Canadian aid agencies, as with other aid agencies, a lot of the funds go to Canadian staff, salaries and travel and that the material is purchased in the donor country. He also says people believe that so much money should have fixed everything, but a lot of the money that was pledged wasn’t delivered.

NGOs poured into Haiti to assist, but it’s unclear how many have been on the ground. There are varying reports placing the number of NGOs in the country to as low as 3,000 and as high as 20,000. While NGOs play critical roles in providing basic necessities and health services to people facing difficult times, there are questions as to who oversees them.

The Centre for Global Development has been calling for the implementation of national guilds that would set a national mandatory requirement for NGOs to be registered, and possibly include a code of conduct that would keep their missions in line with one another. It also calls for practices such as annual reports and audited financial statements.

Canadians responded in the days, months and years after the earthquake. A vocational school was built in memory of RCMP Sgt. Mark Gallagher, who died in the quake.

Gilles Rivard was the Canadian ambassador to Haiti from June 2008 to October 2010 and January 2014 to September 2014. He was in the country when the earthquake struck and says Canada had a fantastic team for the mission. He says Canadian teams brought in food, flew out some 6,000 Haitians and built a new road and a new hospital.

“Now people are complaining that this hospital is not functioning well,” Rivard said. He says if the “Haitian government doesn’t send doctors or nurses to take care of the poor people that suffered, there is nothing Canada can do. But we’re criticized for that.”

Rivard points to issues with UN institutions. He says they “don’t always co-ordinate among themselves.”

“So you can imagine the situation,” he said. “And I think it’s a big problem; the co-ordination and also what we request from the country, the numerous reports, evaluation, audit and so on. They don’t have the capacity to respond.”

Rivard says Haiti needs support from Canada and the U.S., who are main donors.

“Canada does a lot,” he said. “The problem is that if you don’t do enough, you’re going to be criticized. And then if you do too much, they’re going to be accused of telling Haitians what to do. That’s the dilemma.”

Rivard says there is a lot of fatigue from countries that are trying to help Haiti.

“You feel that there is no real progress in terms of governance, of economic situation and so on. So that’s that. See, that’s a vicious circle.”

Father of two Dorcius Fritzner makes his living in Haiti’s capital by shuttling people on his motorbike. He told Global News he’s frustrated with the government. Fritzner says resources in Haiti are barren, likening it to a desert. Issues he points to include children not able to attend school, trouble accessing clean water, unemployment and gas shortages.

Port-au-Prince architect Philippe Léon says the political turmoil and instability has hindered rebuilding efforts. He points to the number of times the government has changed hands; three different presidents and an interim government in the last decade.

“One hundred to 150 years of construction was destroyed, including the presidential palace that was nearly 100 years old,” he said. “It wouldn’t take five to 10 years to rebuild.”

Still, he says, not much has been done. Léon says a lot of the new construction has been in the private sector and a lot of it is half-built. He points to projects like the Village Lumane Casimir, with 1,500 units. Only about half of the units are built, due to a lack of funds.

Léon says Haitians have been building out of necessity. Instead of waiting for the government, people have been building their homes over time.

More than one million people were displaced by the earthquake. In Canaan, about two hours from the capital, tents were set up to temporarily house displaced residents. But today, some people still live in the very tents that were put up 10 years ago. Others have built homes out of whatever they could find; wood and tin homes cover the mountains. A number of residents have built their homes out of cement blocks. People in Canaan have built a makeshift community with homes out of various materials, schools for those who can afford it, churches and grocery stores.

Léon says the mountains surrounding Port-au-Prince are covered with dwellings, with no roads or order. He says when you fly into or out of Haiti at night, you can see all of the lights emanating from homes, snake roads and lack of organization.

Katz says when it comes to Haiti, people often try to find a single villain. Bill and Hillary Clinton are often singled out. But Katz says “what failed was the system.”

“This should be a wakeup call.”

He says inequality, much more than the earthquake, is responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Over the last year, Léon hasn’t worked on any housing projects due to the political instability and violence in his country. He said there’s no work to be had in new builds. Instead, he’s been working on building fences, steel doors and other measures to make homes impenetrable by rioters. At his office, his windows are covered in wood to fend off rocks and Molotov cocktails.

Léon says the problem with Haiti is that the country is “managing misery.” Poverty, a lack of education and fighting for political power are some of the main issues. He says a lot of things other countries take for granted, Haiti cannot. Everything from water to electricity to roads are systems people have to build themselves, and in challenging circumstances.

Léon believes the development of a country “can only happen through its own people, through people who believe in it and support it.” He says the 10th anniversary of the earthquake is time for a ‘bilan,’ an assessment on the progress so far: “counting the blessings and counting your mistakes.” Léon, who is now in his 60s, says he hopes to see a better Haiti himself.

_848x480_1397405763961.jpg?h=article-hero-560-keepratio&w=article-hero-small-keepratio&crop=1&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.