The International Olympic Committee’s loosening of iron-fisted rules around sponsorship gives Canada’s Olympians more commercial wiggle room in Tokyo this summer.

Under pressure from athletes, the IOC now allows for a more liberal interpretation of rules that govern the way athletes engage with their personal sponsors during an Olympic Games.

“We’re seeing a democratization of power,” Canadian Olympic wrestling champion Erica Wiebe said.

Rule 40 of the IOC’s Olympic charter ensures market exclusivity to companies who pony up hundreds of millions of dollars to have their brand in the Olympic Games.

Rule 40 previously stated “except as permitted by the IOC Executive Board, no competitor, coach, trainer or official who participates in the Olympic Games may allow his person, name, picture or sports performances to be used for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games.”

The Canadian Olympic Committee revealed its updated guidelines around Rule 40 for the 2020 Tokyo Games on Tuesday.

Wiebe, from Stittsville, Ont., will be able to interact with personal sponsors on social media more than she could when she won gold in 2016, and appear in advertisements under certain conditions.

“A female wrestler in Canada is a pretty niche market,” she told The Canadian Press. “We’re not Usain Bolt or even Andre de Grasse. We get two weeks every four years to have the spotlight shone on us.

“It would be amazing to thank the people that have supported me since Day 1, that have had my back.”

Jane Roos, the founder of Canadian Athletes Now, or Canfund, has raised over $40 million from the private sector for athletes since 2003.

But every Olympic Games, athletes were silent about Canfund’s contributions because acknowledging it ran afoul of Rule 40.

“When there’s crickets and no one is saying, ‘Thank you’ and our donors say, ‘Do they appreciate it?’ I say, ‘It’s a blackout period,'” Roos said.

“To have athletes being able to say, ‘Thank you’, which I think they should be able to, would help us a lot.”

Rule 40’s wording is now “competitors, team officials and other team personnel who participate in the Olympic Games may allow their person, name, picture or sports performances to be used for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games in accordance with the principles determined by the IOC Executive Board.”

“What’s happened is Rule 40 has effectively not changed at all. It’s the same exact rule that was crafted by the IOC,” explained agent Russell Reimer, who represents several Canadian Olympians.

“What has changed is country to country, athletes have begun mobilizing to change the interpretation of Rule 40 and how it’s ultimately enforced.”

Get breaking National news

German athletes successfully lobbied their country’s anti-trust agency last year to have the IOC’s restrictions on Games-time marketing declared “abusive.”

“This was something we had to pay close attention to, not because of what was happening in Germany, but because of what was important to athletes and their partners and their ability to commercialize themselves during the most important period of their athletic careers,” Canadian Olympic Committee chief executive officer David Shoemaker said.

The COC must still assure its own sponsors they’ll get bang for their marketing buck during the Tokyo Games that open July 24 and close Aug. 9.

So restrictions remain on what athletes can post, say and wear during a “blackout period” from July 14 to Aug. 11.

Wording and images used by athletes and any of their non-Olympic sponsors in advertising and on social media can’t contain any intellectual property deemed Olympic in nature.

“We feel really good about the balance we’ve struck here,” Shoemaker said. “The COC is 98 and a half per cent funded by the private sector through nearly two dozen marketing partners and some of the greatest companies in this country.

“They sign on to a wonderful proposition in Team Canada and in doing so, fund our Canadian sport system. That’s what we’re looking to protect.”

For most of the Canadian athletes bound for Tokyo, more freedom on social media is crucial. Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are their primary means of marketing themselves.

“The Olympics is a brand. They need to protect their brand, but athletes are also brands and they need an opportunity to promote themselves,” Canadian race walker Evan Dunfee said.

“It’s once every four years we get a chance to be seen, so yeah, being able to utilize that opportunity a little bit more certainly is welcomed.”

NHL superstar Sidney Crosby is among the few athletes with the commercial stature to test Rule 40 in recent years.

A Tim Hortons spot featuring Crosby that ran before and during the 2010 Winter Games in Vancouver was the Canadian test case for a non-Olympic sponsor continuing its association with an Olympian during the Games.

American swimmer Michael Phelps did the same with an Under Armour campaign during the Rio Olympics.

The Phelps and Crosby commercials contained no mention of the Olympics or medals or the Games in which they were competing, and thus provided templates for what is allowed now.

But as long as athletes are under contract to competing shoe and apparel companies, there will be tug of war battles.

Think Nike’s Michael Jordan covering his jacket’s Reebok logo with an American flag while standing on the basketball podium in 1992.

Compromise is more elusive outside the Olympic window, when athletes are loyal to the companies paying their bills between Games.

Pole vaulter Alysha Newman pulled out of a COC media day last month because she wanted to wear her Nike gear. The COC’s clothing company is HBC.

“She along with some other athletes have contractual commitments to their personal footwear and apparel brands that conflict with those of the COC,” her agent Brian Levine said at the time.

“Come the opening ceremony … of course they’re going to proudly don the official Team Canada apparel and footwear and all that stuff. They’ve been named to the team, they’re at the Olympics. That’s the understanding.”

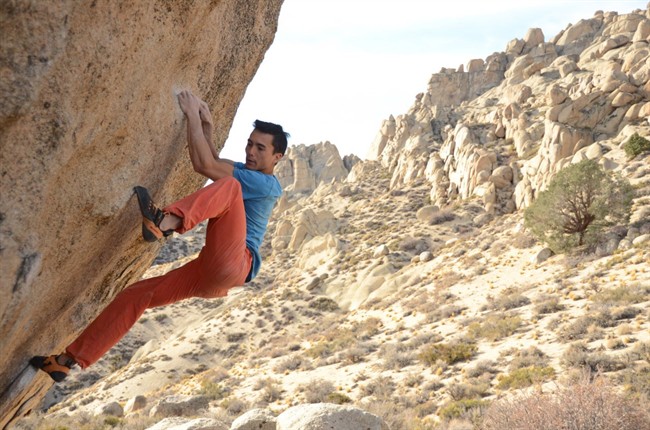

Sport climbing makes its Olympic debut in Tokyo. Sean McColl of North Vancouver, B.C., is already accustomed to accommodating competing sponsors.

He’s backed by Adidas. Climbing events are staked by Mountain Equipment Co-op, so he wears an MEC logo in competition too.

“It’s a big beast,” the climber acknowledged. “It’s kind of like two parallel universes that I’m jumping back and forth in between.

“I think that’s just the way the world of sports is.”

With files from Lori Ewing and Gregory Strong in Toronto and files from The Associated Press.

Comments